Although very few policymakers are thinking about it, now is an ideal time for a bold job creation initiative. The United States is in a period of historically low unemployment. At the time of this writing, the country has had monthly unemployment rates under 4 percent for over two years. This is good news. But even with this low unemployment rate, there are still millions of people who need jobs.

When the number of people officially unemployed, the people who want to work but aren’t officially counted as unemployed, and the people who want full-time work but can only find part-time work are added together, the country averages about 17 million people who have insufficient work. (As of April 2024, that number was 16.6 million people).

This joblessness can be found in every part of the country and among all racial groups. For example, the national unemployment rate averaged 3.6 percent in 2023, but it was 7.2 percent in Calhoun County, WV, and 9.8 percent in Magoffin County, KY. These are majority-White counties. The unemployment rate as of April 2024 is 8.4 percent in Coachella, CA, and 8.9 percent in Yuma, AZ, which are majority-Latinx cities. That same month, the unemployment rate was 7.4 percent in Detroit, MI, and 7.2 percent in Jefferson County, MS, both majority Black communities.

In 2023, the United States had the lowest annual Black unemployment rate since 1972. But the labor market is still significantly better for White people than for Black people.

The sad fact is that even during this period of historically low unemployment, it is very easy to find places with unemployment rates two or more times the national rate in nearly every state. While all racial groups have communities that experience high rates of unemployment, the problem of joblessness is especially acute in Black communities, as national figures demonstrate. For example, the latest national unemployment statistics from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (May 2024), show that White unemployment is at 3.5 percent compared to Black unemployment at 6.1 percent; Black unemployment, in others words, is more than 70 percent higher.

Black Joblessness Is a Major Driver of Black-White Income Inequality

Economics is sometimes described as the dismal science, but there is some good economic news of late: the low-unemployment era has reached Black America. In 2023, the United States had the lowest annual Black unemployment rate since 1972. But the labor market is still significantly better for White people than for Black people.

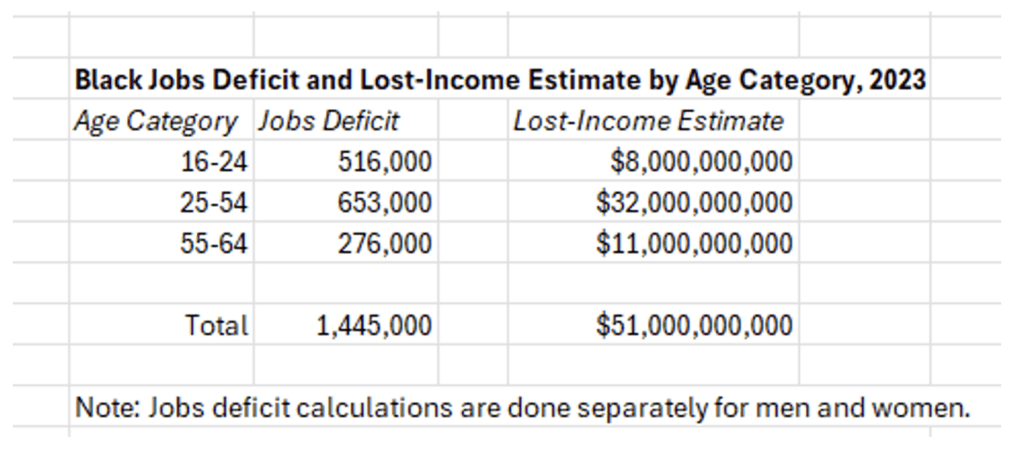

To understand the impact of Black joblessness, consider what I call the “Black jobs deficit.” The Black jobs deficit calculates the number of jobs needed for Black people to be employed at the same rate as White people. Based on federal data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Census Bureau, in 2023, 54.2 percent of White male youth ages 16 to 24 were employed, but only 44.2 percent of Black male youth in this age group were employed. This Black male youth jobs deficit of 10 percentage points translates to 282,000 more Black male youth who needed jobs to have the same employment rate as their White peers.

For females, again, 54.2 percent of White female youth were employed, but 46.3 percent of Black female youth were employed, which is close to an 8 percentage points jobs deficit or a gap of 234,000 “missing” jobs for Black female youth.

The table repeats this process for three age categories. It also multiplies the number of jobs by the 2022 personal income amount for the most similar Black age category. This produces a rough estimate of the income lost to Black Americans due to the job deficits.

In 2023, the total Black jobs deficit for ages 16 to 64 was almost 1.5 million jobs. This number is for the year with the lowest Black unemployment rate since the 1970s. This amount of joblessness translates to roughly $50 billion in income that Black Americans did not obtain in 2023.

If policymakers, advocates, and philanthropists wish to reduce Black poverty, they should be dedicating more resources to job creation. Data scientists examined what changes in terms of work and wages would be necessary for Black America to have a parallel income distribution to White America. The researchers found that 60 percent of the Black-White income gap was due to insufficient work; 40 percent was due to lower wages. Although more than half of Black-White income inequality is due to insufficient work, is the US government devoting a proportionate share of antipoverty resources to job creation?

Clearly not.

A Targeted Subsidized Employment Program Can Help

Subsidized employment programs are much more effective than giving tax credits to corporations and wealthy investors to create jobs.

The current low national unemployment rate is the result of favorable economic conditions over recent years. For several years, beginning in 2008, the Federal Reserve kept interest rates very low, spurring economic growth. Those low rates contributed to a strong trend of increasing employment rates for all groups and helped narrow the Black-White gap in employment rates. But importantly, years of low interest rates were not enough to eliminate the gap.

While the COVID-19 pandemic caused a severe recession, broad-based federal emergency relief policies helped to rapidly repair and rejuvenate the labor market. In spite of the efforts of the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates as a means of fighting inflation, job growth has continued. In 2023, the employment rate for the 25- to 54-year-old Black population was at its highest point in this century. But even at this high point, there remains a Black-White gap in employment rates.

While low interest rates and broad-based stimulus policies are helpful in narrowing the Black-White employment gap, they have never been enough to eliminate the gap entirely. A targeted intervention could make a significant difference. The best targeted intervention is a federal subsidized employment program focused on communities experiencing a high rate of joblessness.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Subsidized employment is when the government or some other entity covers some or all of the labor costs of hiring workers. This is one of the most effective and efficient means of job creation. When well-designed and targeted, these programs can pay for themselves due to the reduced need for social welfare spending, the long-term increase in tax revenues from effective short-term programs, and the reduction in crime and criminal legal system costs.

Subsidized employment programs are much more effective than giving tax credits to corporations and wealthy investors to create jobs. I refer to the tax-credit approach to job creation as a “give-money-to-the-rich-and-hope” approach because, typically, the country gets very little job creation for the cost.

The federal government has subsidized employment for large numbers of Black people before, and it can do it again.

For example, researchers have found “little or no evidence of positive effects” on disadvantaged communities from the Trump administration’s Opportunity Zones tax-reduction program, in spite of it being a relatively large amount of spending. The program, of course, did help the wealthy who received the tax breaks. Unlike the tax-credit approach, with subsidized employment, the government does not spend money without receiving jobs in return.

Some might favor a broad-based federal jobs guarantee instead of a program targeted to places like the ones mentioned in the opening of this piece. There are many challenges to a jobs guarantee. The one most important to our current moment is the high risk that a jobs guarantee will be inflationary. A more targeted subsidized employment program is not likely to spur inflation.

Even if one wishes to establish a job guarantee, a targeted approach is a good way to begin to phase in a broader program. For example, Representative Bonnie Watson Coleman (D-NJ) sponsored the Federal Jobs Guarantee Development Act of 2023, a pilot subsidized employment program targeting high-unemployment places, not a universal program.

Designing a Good Subsidized Employment Program for Black America

There is a long history of subsidized employment. The largest programs were created in the wake of the Great Depression. It is important to remember that in 1939 the Works Progress Administration created over 400,000 jobs for Black workers. Given the growth of the US population, 400,000 jobs in 1939 would be equivalent to about 1.4 million jobs today. The Civilian Conservation Corps from 1933 to 1942 also provided employment for about 200,000 young Black men. The federal government has subsidized employment for large numbers of Black people before, and it can do it again.

For communities like those mentioned above, subsidized employment programs need to be designed with a Depression-era sensibility because these communities are economically distressed. They have suffered from years of economic underdevelopment and consequently have high rates of joblessness.

Many subsidized employment programs are designed as quasi-job-training programs. These programs are of a very short duration, apparently because the designers assume that once individuals learn particular skills, they will easily find nonsubsidized employment. This approach will not work in communities suffering from persistent poverty, however. These areas have a high rate of joblessness because there are too few jobs. The fact that these communities have such a high rate of joblessness when there is a low national unemployment rate indicates that the local economy is experiencing circumstances very different from what is happening elsewhere.

Black workers also experience racial discrimination in the labor market. Researchers consistently find that employers are less likely to hire a Black person than a White person when both individuals have the same qualifications. Because of decades of a racially targeted “war on drugs” and mass incarceration regime, many Black individuals also have formerly been incarcerated. Because of the socioeconomic determinants of health, including a racially inequitable healthcare system, Black Americans are more likely to have disabilities. These are additional factors that lower the odds of Black people finding work. A job-training-like program does not counteract these forms of discrimination in the labor market.

To address the employment needs of communities that have been underdeveloped and populations that face labor market discrimination, subsidized employment programs should offer employment for one year, at minimum. Indeed, programs that run for a year or more have been shown to have better long-term outcomes for participants. While subsidized employment programs for communities and populations facing underdevelopment and discrimination should not be designed as quasi-job-training programs, including opportunities for job training and other wraparound supports (such as childcare and transportation), are beneficial.

These programs should also be part of a broader economic development plan. Essentially, they are an economic development investment.

Now Is an Ideal Time for Subsidized Employment

During periods of low unemployment, policymakers, advocates, and philanthropists tend not to think about developing jobs programs. This is unfortunate because it is at precisely these times that job programs can be most effective at identifying and improving the lives of the most disadvantaged individuals.

The communities and populations suffering from high rates of joblessness during a low-unemployment era are the communities and populations with the most severe labor market challenges. These groups can be more easily identified and better helped during periods of low unemployment.

A large-scale federal program would be best, but it is also possible to enact subsidized employment programs at the state or local levels. Indeed, just about every state with a significant Black population has a Black jobs deficit. Cities with large Black populations are also likely to have Black job deficits. The time to close these deficits is now.