Editors’ note: This article was excerpted, with minor edits, from Ideas Arrangements Effects: Systems Design and Social Justice (Minor Compositions, 2020), for the summer 2020 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly. This edition of the magazine is about the need to understand the often unacknowledged and unspoken design principles behind some of the practices and structures that pervade our work. We recommend the book highly. All illustrations are by Ayako Maruyama.

Activists, artists, philanthropists, young people, academics—all manner of folks—constantly battle injustices and negative effects in their lives and the lives of others. We take to the streets, to the Internet, to the voting booth, and more to fight for better outcomes. To the same degree, we argue vehemently about the ideas that underlie these injustices—from notions of public and private to ideas about categorizing our bodies, to all the “isms” that say some categories (and people) matter more than others.

But the arena for intervention that we at DS4SI want to make a case for is a less obvious one: that of the multiple, overlapping social arrangements that shape our lives. We believe that creating new effects—ones that make a society more just and enjoyable—calls for sensing, questioning, intervening in, and reimagining our existing arrangements. Simply put, we see rearranging the social as a practical and powerful way to create social change. And we want those of us who care about social justice to see ourselves as potential designers of this world, rather than simply as participants in a world we didn’t create or consent to. Instead of constantly reacting to the latest injustice, we want activists to have the tools and time to imagine and enact a new world.

As Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, wrote in her 2018 debut op-ed for the New York Times:

Resistance is a reactive state of mind. While it can be necessary for survival and to prevent catastrophic harm, it can also tempt us to set our sights too low and to restrict our field of vision to the next election cycle, leading us to forget our ultimate purpose and place in history….Those of us who are committed to the radical evolution of American democracy are not merely resisting an unwanted reality. To the contrary, the struggle for human freedom and dignity extends back centuries and is likely to continue for generations to come.1

With the weight of lifetime Supreme Court appointments or healthcare or climate change seeming to hang in the balance of our elections, it is easy to get stuck there. But as Alexander points out, our fixation with politics and policies as the grand arrangement from which all other forms of social justice and injustice flow serves to “set our sights too low.”2 When do we get to imagine the daily arrangements of “human freedom and dignity”?3 We know this won’t happen overnight. It takes time and investment for social arrangements to institutionalize and endure, and it will take time to change them. But it is critical that we try. And to do that, we need to be better at sensing arrangements, intervening in them, and imagining new ones.

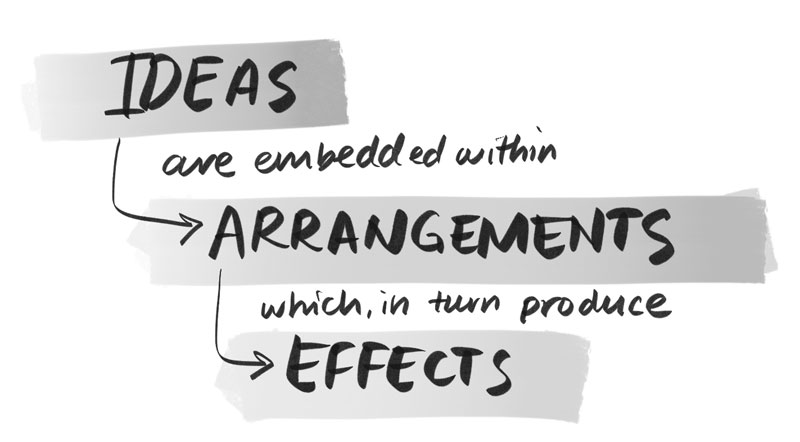

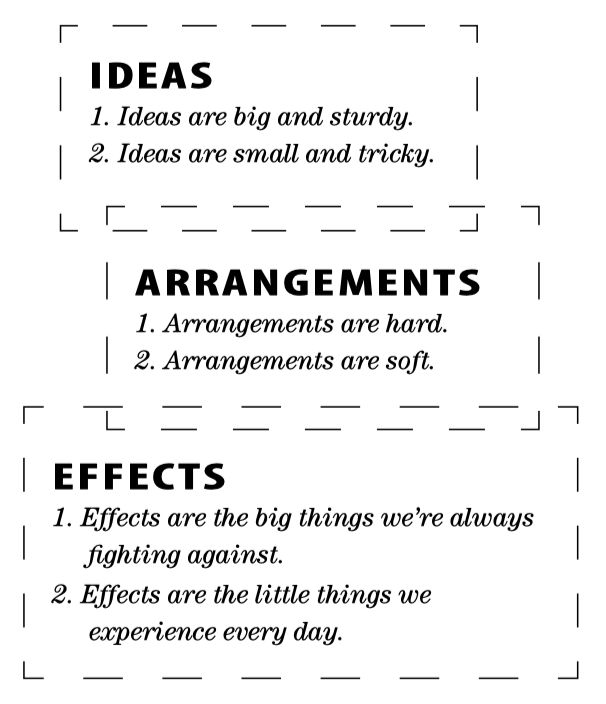

BREAKING DOWN IDEAS ARRANGEMENTS EFFECTS

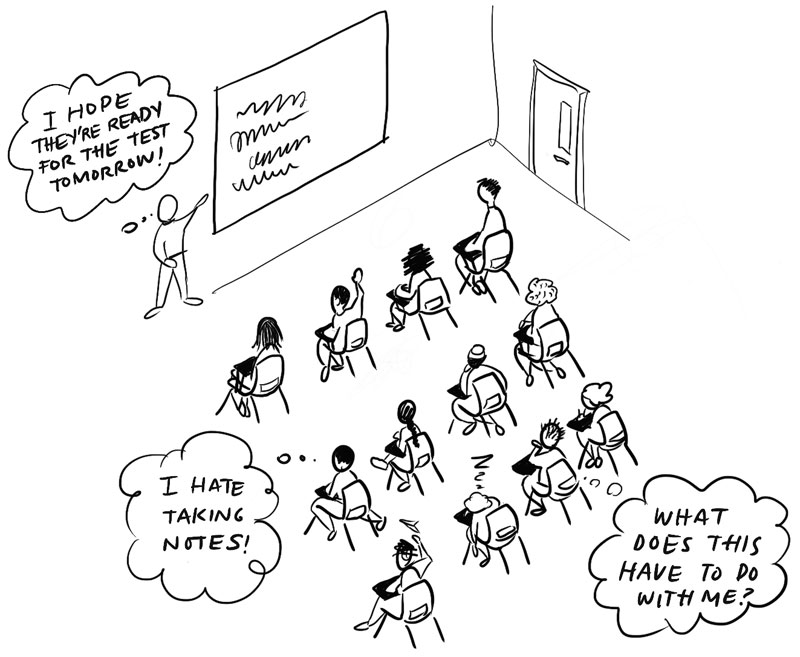

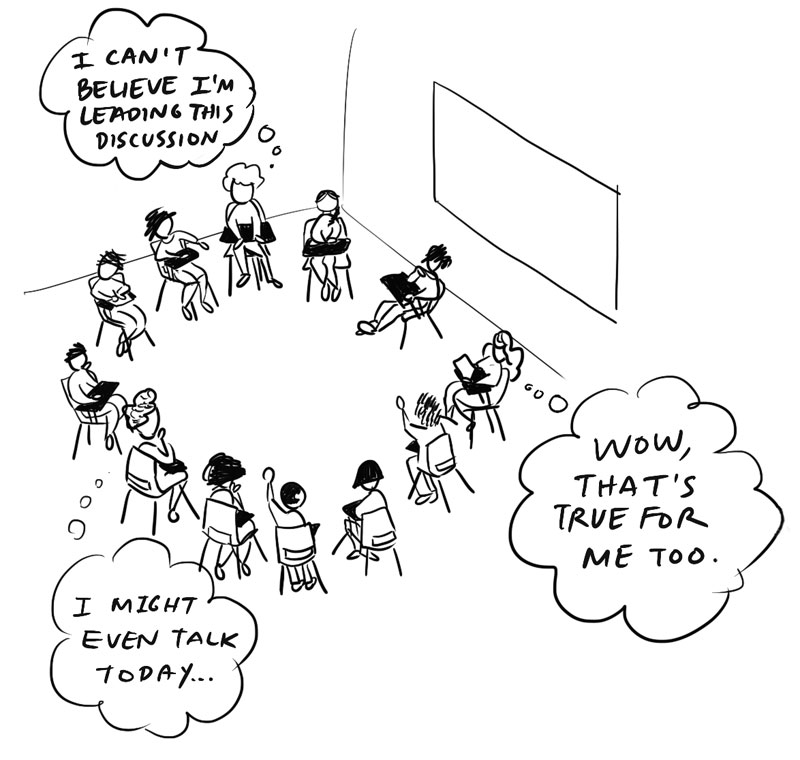

Ideas are embedded within social arrangements, which in turn produce effects. One simple way to explain this premise is in the arrangement of chairs in a classroom. When we see chairs in straight rows facing forward, we believe the teacher is the head of the class and that knowledge flows in one direction—from the teacher to the students. In response to this, many workshop facilitators and adult-ed teachers rearrange the chairs into a circle, with the idea being that knowledge is distributed across the participants and could emerge from any place within the circle. The rows are one expression of ideas about how learning happens; the circle is another. The effects that rows or circles of chairs have on learning are important, but they are not the point here. The point is that the arrangement produces effects.

When we scan out from the common example of chairs in the classroom to the complex social arrangements of everyday life, the principle still stands: Ideas-Arrangements-Effects. They just get more intermingled and complicated. For example, arrangements like “work” flow from a myriad of ideas—weaving together ideas about value, labor, capitalism, citizenship, gender, etc. Effects of our current arrangement of “work” range from unemployment to burnout, from poverty to immigrant bashing, from anxiety to loneliness, etc. As activists, we often attend to the effects because they are urgent—fighting for an increased minimum wage to decrease poverty, for example. As social justice practitioners, we also think a lot about the ideas that often lead to negative effects—like how racism or sexism influences who gets the higher paid positions (or even who gets hired). But the underlying arrangement of “work” is often taken for granted.

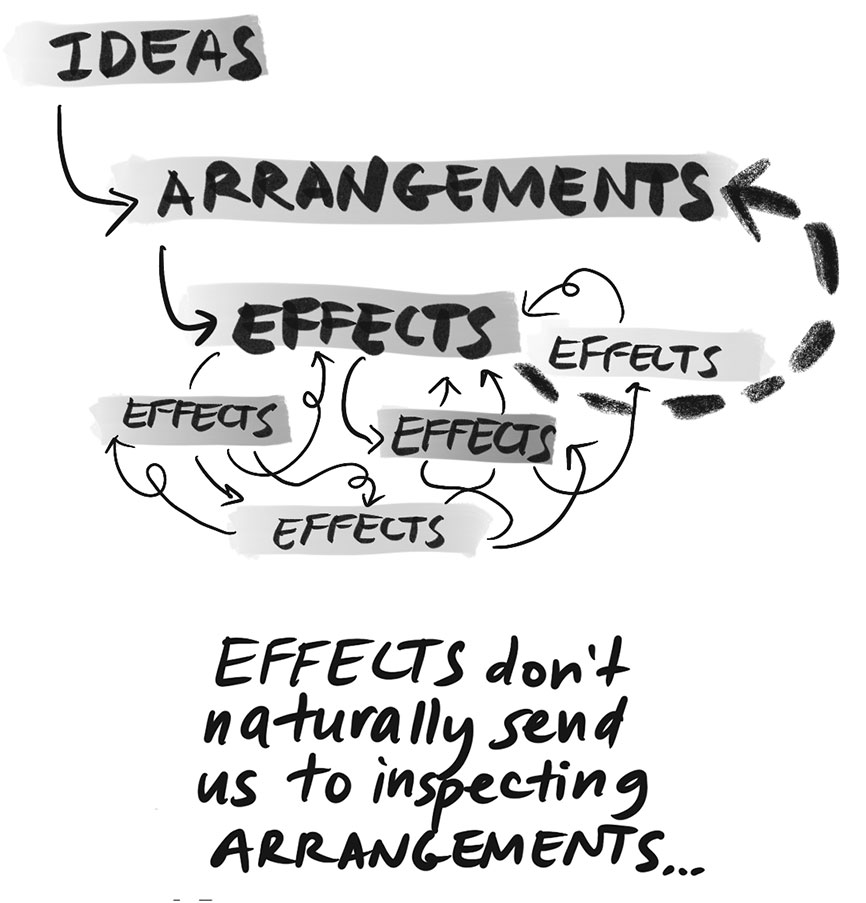

To compound this, effects don’t naturally send us to inspecting arrangements. They send us back to other similar acute experiences, rather than the distributed elements of arrangements. And if we do think about arrangements, they can seem daunting.

The rearranging of chairs is much easier to do than rearranging our conceptions of time, sociality, or other institutions that glue daily life together and give shape to our collective experiences. To make things more challenging, the older and more codified the arrangement, the farther it falls from the capacity to be perceived, let alone changed. These larger, sturdier social arrangements move into the realm of social permanence. For example, cars. We might argue for safer cars, greener cars, fewer cars, or driverless cars—but do we ever ask the question, “Are cars as a social arrangement still beneficial? And if not, how do we proceed?”

We believe that the I-A-E framework can both deepen our understanding of the social contexts we hope to change and improve, as well as expand our capacity for designing the world we truly want.

To begin, we will share some insights we’ve developed about each part of the I-A-E framework—ideas, arrangements, and effects—and then lessons we’ve learned for how the parts relate to each other and interact.

Ideas

Many times, as humans attempt to create change, we go back to the ideas behind the injustices we are trying to address. Whether those ideas are notions of democracy, justice, or race, we often get trapped in familiar discourses—complete with familiar arguments and even familiar positions and postures. (For example, when conversations about democracy get limited to Democrats and Republicans, or debates about education revolve around school budgets.) We argue heatedly and repeatedly about the big ideas, and we get trapped there without inspecting smaller ideas and what opportunities for change they could open up. The discourse itself becomes a trap. It rehearses itself and normalizes itself and ossifies the conversation, falling into well-worn grooves. It ceases to have rigorous curiosity, because to vary from the beaten conversation feels dangerous or odd. We want to look at ideas both big and small, both well inspected and largely uninspected, as we think about how they relate to arrangements and effects.

1. Ideas are big and sturdy.

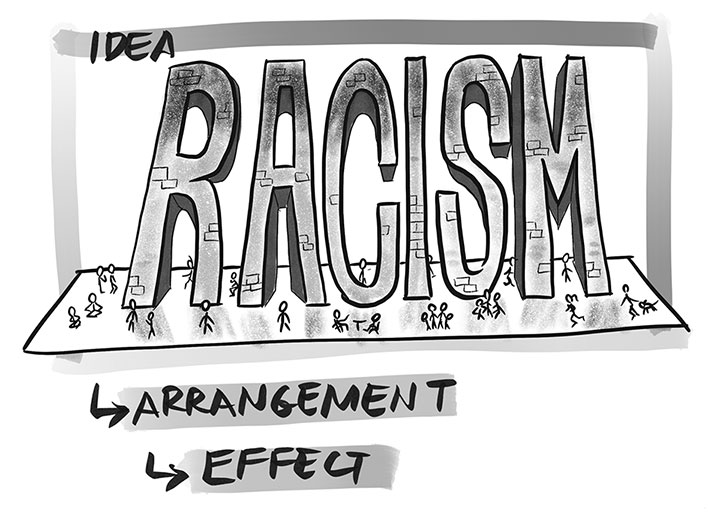

Oftentimes, we jump right from unjust effects (achievement gap, gentrification, police violence, poverty, etc.) back to the big ideas that repeatedly produce them—ideas like racism, classism, homophobia, and sexism. Big ideas aren’t limited to the “isms” of course; they also include long-held notions about freedom, progress, the American Dream, private property, gender, democracy, and many others.

Big ideas remain sturdy because of how they embed themselves in everyday life. This used to be more obvious than it often is today. For example, racist ideas in the 17th century were explicit in institutions like slavery, and then just as obvious in the later public infrastructures of “white” and “colored” water fountains and whites-only bathrooms in the South. While we no longer have slavery or whites-only bathrooms today, we clearly have racism raising its sturdy head in countless other ways. In addition, we have examples of other “isms” directly embedded in current arrangements today, such as transphobia and the renewed ban on transgender people in the military, or adultism and the age limit on voting.

We need to name “isms” when we recognize them, and we need to listen to others who recognize them when we do not. Using the I-A-E frame can also increase our repertoire for recognizing them as they embed themselves in the arrangements and smaller, trickier ideas shaping what we call everyday life.

The ubiquitous “white” and “colored” water fountains of the past have been removed, but the countless ways that Blacks are targeted while doing daily things like driving, shopping, or resting show that racism continues to be a sturdy idea.

2. Ideas are small and tricky.

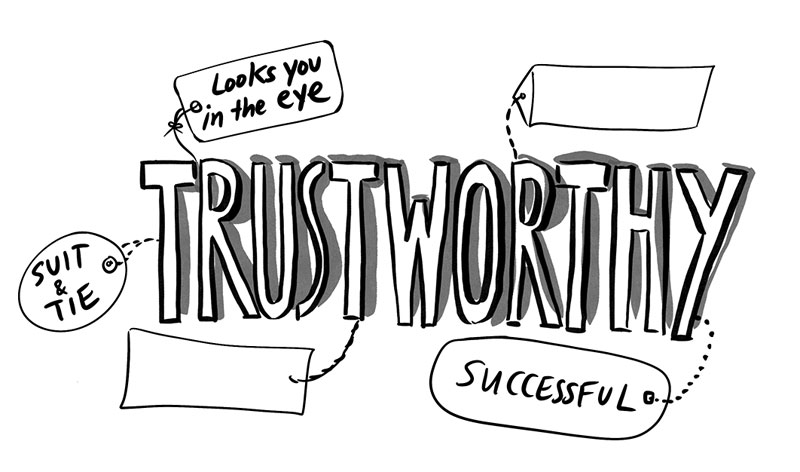

We deploy (and hide) our big ideas by embedding them in our beliefs about daily life—they become whitewashed, so to speak, as more “innocent” values, beliefs, and ways of life. They fall from the realm of critique and dialogue and into the realm of expectations and assumptions.

A few examples of these “innocent” ideas include:

- How to dress (or eat, or speak) “appropriately”

- Who should be listened to, believed, or trusted

- How big your body should be or how loud your voice should be

- What healthy food is, what good food is, or what food you should (and shouldn’t!) bring for lunch

- Who the audience is for public life and culture

- What and who is attractive

- What qualifies someone for a job

- What makes a neighborhood “safe” or “dangerous”

We know how to call out racism, but do we know how to intervene in “appropriate” or “trusted” or “welcome”? When the whites-only water fountain gets replaced by the whites-mostly coffee shop or beer garden, we only know how to point it out when a Black person is explicitly treated unfairly. We don’t frequently challenge the numerous tricky ideas (consumerism, aesthetics, etc.) that whitewash those spaces in the first place.

The clearer we get on the specifics of the coming together of arrangements and the ideas embedded in those arrangements, the more ideas we might have for creating change, and the more site-specific and useful points of leverage we might find. We need to get better at understanding how big ideas have become ingrained in the operating system of everyday life—how something as seemingly innocent as being a fan of a major sports team (complete with its jerseys, rituals, parades, stadium, etc.) can stand in for tribal whiteness and manliness. When we can find the more subtle and tricky ideas expressed in the workings of our lives, we get better grips on the kinds of changes we can make.

How sturdy ideas like racism get embedded in tricky ideas like…

Arrangements

Arrangements give shape to our shared experience. They are all around us, at all sorts of scales, overlapping, creating both order and chaos as they flow over us and under our consciousness. Arrangements include the football season with its schedules, stadiums, and fantasy leagues; the highway with its cars, speed limits, and exits; the grocery store with its rows and stacks, prices, and cash registers; Christmas with its work holidays, shopping, wrapping of gifts, and assumptions of Christianity; the 9–5 day; the police; and the list goes on. We tend to participate in the arranged because it is our shared social container. And for the most part, we simply take it for granted. This is one reason we at DS4SI pay so much attention to arrangements. They are a rich and frequently overlooked terrain for creating change.

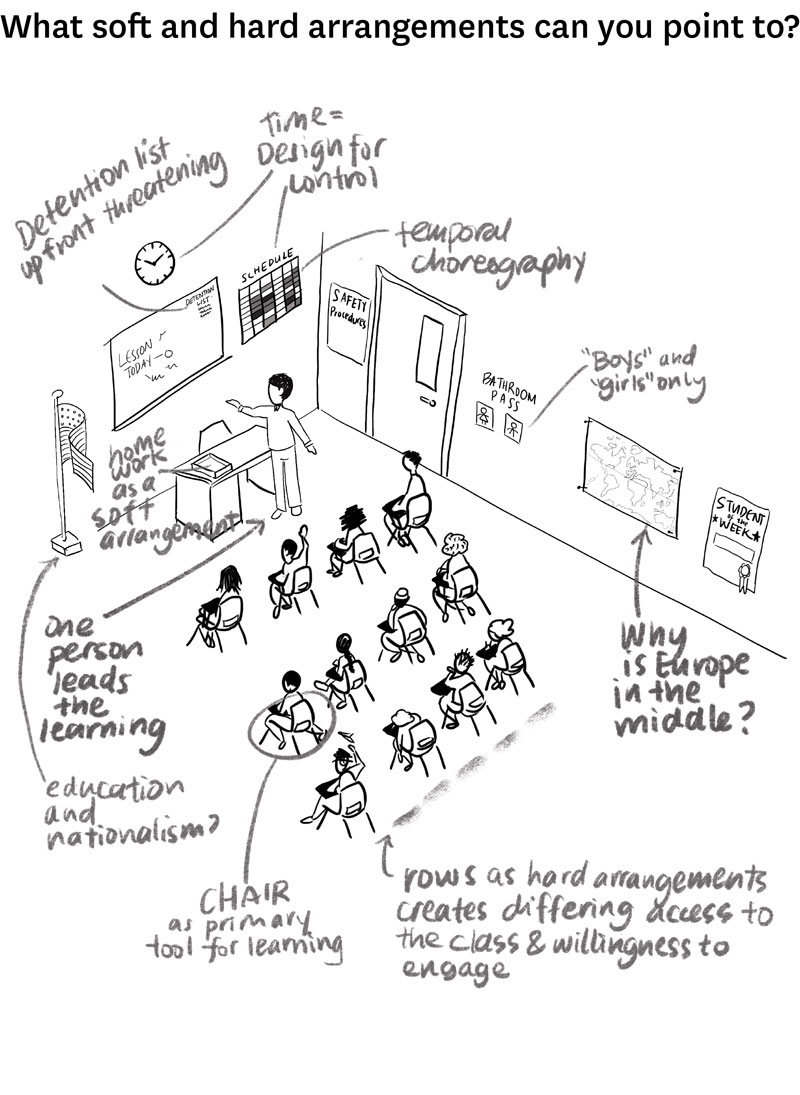

We can talk about such arrangements as “how the chairs are arranged in the room,” which is what we call a “hard” or physical arrangement. We also talk about the chair itself as an arrangement for learning, as something that conveys that bodies should be passive while they learn. When we overlap that with how students are supposed to listen to their teachers or raise their hands before speaking, we start to point at what we call “soft” arrangements—which can be even sturdier than the chairs themselves, but harder to point to.

What soft and hard arrangements can you point to?

1. Arrangements are hard.

We have the architectural and industrial arrangements of built things like desks, buses, and cities. These are the easiest to point to but in some cases the hardest to rearrange (depending on scale). It is a lot easier to rearrange chairs than to rearrange a built environment. Hard arrangements range in scale from the toilet, chair, or bed, to airports, strip malls, and industrial farms.

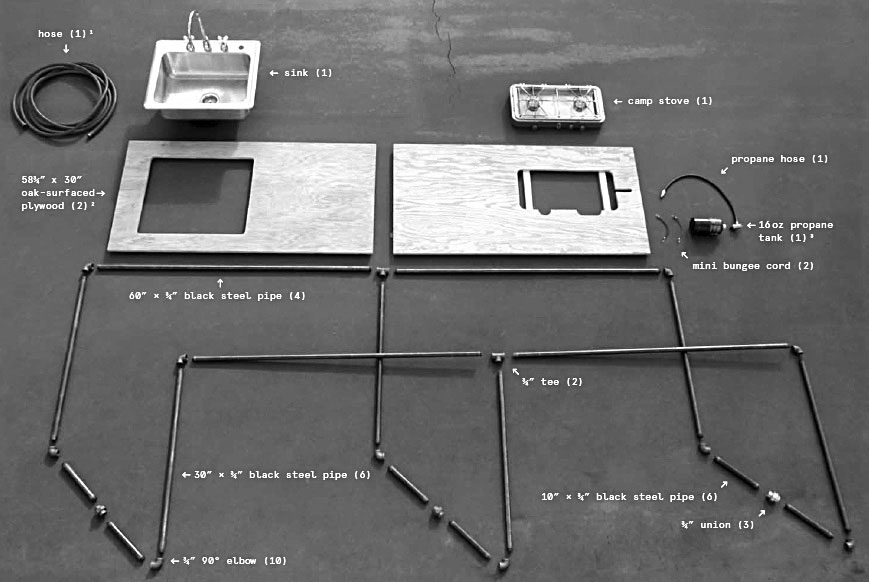

We explored the hard arrangement of the kitchen in our intervention Public Kitchen. We wanted to point to how many elements of our daily lives flow from the assumption that everyone has a private home with its own kitchen. We wanted to explore how daily life could be more convivial and affordable if we had an arrangement like a public kitchen. We began with the question: If we had public kitchens—like public libraries—how would it change social life? What other arrangements—both hard and soft—would grow out of such an infrastructure?

2. Arrangements are soft.

Soft arrangements are the less tangible arrangements—how routines, expectations, and long-held assumptions shape the everyday. They include routines like how the day is punctuated by breakfast, lunch, and dinner, or arrangements that put “girls” and “boys” on different sports teams or in different bathrooms, or that there is such a thing as “normal” or “deviant,” and we create arrangements like jail for the “deviant.” A relatively new set of arrangements have cropped up on the Internet—from social media to online shopping to fantasy football, each with its own ways of shaping our everyday.

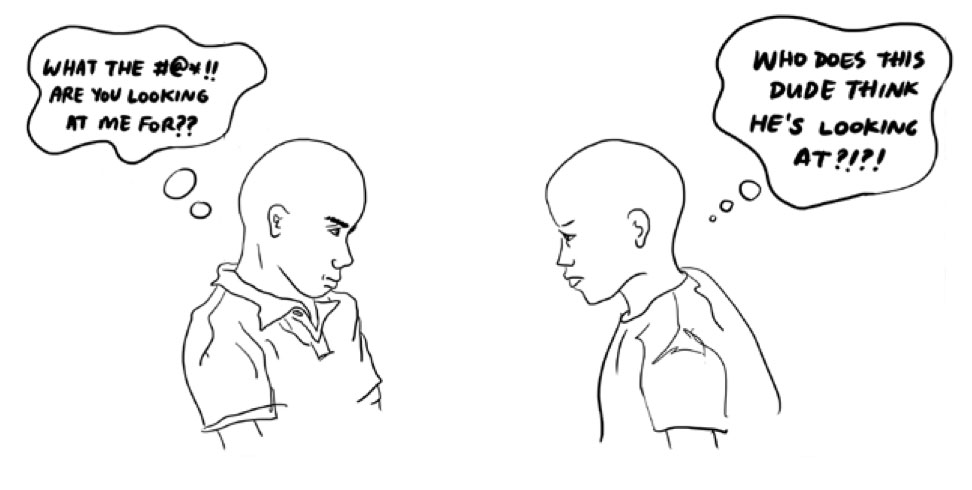

Since arrangements are both hard and soft, looking at and for social arrangements requires a fairly broad set of competencies. To make things more complex, arrangements are constantly intersecting and interacting. Think about two youths grilling each other. They are in the immediate arrangement of grilling, while simultaneously being in the hard arrangement of a school hallway, public bus, or street, in the soft arrangements of identity (“big brother,” “butch dyke,” “new kid”), or the multiple arrangements of hanging out with friends, heading to work, etc. In that sense, effects are emergent properties of multiple overlapping hard and soft arrangements. When we want to fight effects like “youth violence,” we would do well to look at multiple arrangements: the overcrowded bus or school hallway, the lack of youth jobs or affordable transit, and even the agreements embedded in the grill.

In the Grill Project, we explored the soft arrangement of how youth feel that if someone looks at you hard (grills you), you have to grill them back.4 It felt completely unchangeable to them. If they didn’t grill back, they were a punk. We were trying to uncover and disturb the often dangerous daily arrangements and agreements about what it takes to “be a man” or prove your toughness (including for girls).

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Creating new effects—the ones we believe will make life more just and enjoyable—then calls for questioning, changing, and reimagining multiple arrangements. Just as activists call for intersectional thinking in how we think of ourselves and our struggles, we believe we need to understand the intersections of multiple hard and soft arrangements if we are going to truly challenge social injustices.

Effects

We use the term “effects” to talk about the impacts that ideas and arrangements have on our everyday life and larger world. These include the large-scale effects of injustices based on racism, classism, sexism, etc.—effects like the achievement gap, vast income and health disparities, and the underrepresentation of women in the U.S. Congress. They also include the more mundane effects generated by everyday arrangements like public transit, men’s and women’s bathrooms, Facebook “likes,” etc.

1. Effects are the big things we’re always fighting against.

Effects are dramatic. They are everything from climate change–related flooding to the police shootings of Black people. They stir up our passions. They make us want to act. Effects are the things that make the news on the one hand, and are the topics of our conferences and meetings on the other. Food scarcity, the opioid crisis, low literacy rates, school shootings (or closings), climate chaos, and gentrification all fall under the concept of effects in this framework.

On a brighter note, as we look to create change and address injustice, success can show up in a variety of big effects, some of which we can hardly imagine. These could range from soaring success rates for students in fully resourced public schools, to zero police shootings in a city that disarms its police force, to an uptick in Gross National Happiness (GNH), the index put forward by the small nation of Bhutan to contrast with capitalism’s obsession with the GDP (Gross Domestic Product).5

2. Effects are the little things we experience every day.

We experience numerous effects all the time. We live them as good or bad outcomes of the arrangements of our world. They are the bus always running late, the stress of rent we can’t afford, the water we can’t drink, the lack of jobs for our kids, etc. They are the fight at school between kids who spent too long sitting in those rows, or the feeling of invisibility for folks of color in a city that whitewashes its public spaces and promotions. Conversely, they are the good mood after playing basketball in a public park, or the feeling of friendship after discussing your shared love of books with a fellow commuter.

With I-A-E, we inspect the small effects as much as we do the big ones. We hold them up to scrutiny, and speak to the meta-effects of the accumulation of small effects. What level of constant suspicion, surveillance, and disrespect adds up to the “toxic stress” that contributes to the higher rate of heart conditions in the Black community?6 What combination of job discrimination, rent going through the roof, and widespread homophobia leads to homelessness in the LGBT population? While we dedicate protests, nonprofits, campaign speeches, and conferences to the meta-effects, how do we measure or make sense of the vastly different experiences we might have just getting to that protest or conference? We posit that a deeper awareness of small effects will give us new ideas for interventions or even whole new arrangements.

HOW I-A-E COMES TOGETHER (and wiggles around)

I-A-E is meant to be a useful framework for those of us looking for new ways to create change, be they new “levers” or points of opportunity, new approaches, or even new arrangements. We find it helpful in catching us when we default to familiar arguments or put too much weight on a particular candidate or policy. Here are a couple of ways that I-A-E helps us broaden our palette for understanding how to make and assess change.

Why I-A-E Rather Than I-P-E

Shaking the habit of thinking Ideas-People-Effects (I-P-E)

As humans, we are prone to thinking “I-P-E” or Ideas-PEOPLE-Effects. That means we tend to look for whom we can blame when we experience negative effects. This leads us to believe that effects emerge from the deficiencies of individuals, rather than flawed arrangements. Think about when you are waiting in line for a bus that’s late, and everyone gets a little mad at everyone else. It is really easy to get irritated with the person who is talking too loud on the phone, or pushing, or who smells bad. But we tend not to ask the bigger questions about why there aren’t more buses, why the roads are so crowded, or why more people can’t walk to where they need to go.

It is this human propensity to think I-P-E that also leads us to blame individual people for their problems or ours: to blame parents for childhood obesity or individual cops for state-sanctioned violence. This leads us to “solutions” like healthy eating classes or police body cameras, rather than challenging the sturdy arrangements of our industrial food systems or criminal justice system. It also makes us think that individual people can solve their problems, or ours—as if someone who learned how to eat and cook correctly had any more of a chance of solving childhood obesity than President Obama did of solving the problems of a democracy founded on slavery and capitalism.

When we use I-A-E instead, it helps us inspect how ideas about health and safety (and race and gender) become embedded in a multitude of arrangements—from the fast-food chains to the healthy eating class, from police forces to school-to-prison pipelines. It helps us both understand and question the intersections of those arrangements and how they define certain people as problems. It helps us stop hating the player and start hating the game. This is critical, because as arrangements age and join forces with other arrangements, they assume power as the given backdrops of our lives. Their survival becomes more important to themselves and others than the sets of people for whom they might not work. We can’t let that discourage us. Using I-A-E can help us find new ways to challenge arrangements—and imagine new arrangements altogether—as methods that can lead to greater change.

How We Arrange Ourselves and Each Other

Inspecting the ways we collude with power

The ways we talk to each other, look at each other, think and feel about each other and ourselves are as much a product of ideas, arrangements, and effects as chairs, buildings, and other tangible arrangements of daily life. As we’ve said, arrangements are both hard and soft. For those of us concerned with social change, this means that social life—and the myriad of soft arrangements within it—is a rich terrain for intervention.

We can use the I-A-E framework to inspect the presuppositions embedded in our speech and thought habits just as we use it to inspect how ideas are embedded in exterior arrangements of everyday life. How we think and talk, as well as who we talk to and who we listen to, are arrangements that produce effects: they arrange and limit who we are and who others can be in our world.

We arrange each other every time we enact categories of social hierarchy, which means pretty much every time we interact. We arrange ourselves in small, quotidian ways with assumptions embedded in a title (Mr.? Ms.? Mx?) or the sense that no title is needed at all, or with assumptions about interests, parenthood, education, or sexual orientation. Speech patterns follow, as varied as the man-to-man greeting of “Did you see the game last night?” to the array of racial euphemisms, from “at-risk” to “underserved” to “diverse,” to the functions of who speaks and who listens in our earlier example of chairs in rows in a classroom. These kinds of speech acts go unexamined in our larger social lives, but they are not innocent. What kinds of essentialist claims get reified and projected outward? Whose priorities are reflected in the implicated social arrangements?

We arrange ourselves and each other in larger ways as well. When DS4SI came up with the idea of the Public Kitchen, people assumed we meant a soup kitchen. They immediately perceived it as a service, and in so doing, they arranged the always-other, always-needy people who would use it. Even after we created a space that brought people together across culinary talents and economic backgrounds, our funders asked, “Did you do a participant evaluation?,” not realizing that the very act of asking people to fill out that form would have meant arranging them into a category of service recipient or program participant.

Similarly, when organizing groups speak of “their base,” they risk falling into thought habits that arrange the very people they are fighting for and with. If we think of our base only as a source of power that we need to “turn out” or “build up,” or as a mass of victims of oppression, are we also able to see them as nuanced individuals who might have very different ideas about our work, their neighborhood, the issue at hand, or even what we serve to eat?

Another way we arrange entire communities is by making generalized assumptions about their expertise. Take the notion that people are “experts on their experience.” This can begin as a useful approach to youth work or community organizing: adults going to young people to truly ask them about their lived experiences, or organizers doing “one-on-ones” to listen to what the community cares about. This is important work even if we used to be youths ourselves, even if we are from that community, etc. But it is also the work of arranging people, unless we listen for a vast array of expertise. Do we expect youth to want to organize around “youth issues” like education, or can they be fired up about housing or interpretation services? Do we only expect community members to be experts on the challenges of life in their community, or can we also see them as experts in carpentry, systems analysis, education, or acting?

To address these ways that we arrange ourselves and others, we have to get better at seeing where our current speech, thought, and communication habits collude with the world we are fighting against, collude with power. Sometimes it comes from overlapping arrangements—our arrangements of thought reinforced by positions of power: our role as supervisor, teacher, organizer, or service provider. When our work puts us in charge of people, knowledge, or resources, there are fixed choreographies that we slide into. We have to start with the realization that this is a familiar dance, and ask ourselves, “What is this choreography of interaction doing to us and others? What does it afford and deny?” These dances might be fun (or at least convenient), but they impose presuppositions that we might not want to enact. If we are to imagine a new world, we must not only question the current one, but question how it has arranged our own habits of thought, speech, and interaction with others.

When I-A-E Is Multidirectional

Keeping an eye out for the nonlinear

I-A-E is a conceptual framework for understanding and engaging with each part of the equation—the ideas, the arrangements, the effects—as well as with the equation as a whole. It gives us a clearer sense of the entire terrain that we are intervening in, and with that, a wider set of options for creating change. That said, it is neither as clean nor as linear as it might appear. One thing we know about systems—both conceptual and literal ones—is that they can back up on you! So even as we keep in mind that “Ideas are embedded in Arrangements, which in turn yield Effects,” we understand that the equation can go in all sorts of directions: Arrangements can yield new ideas. Effects can yield new arrangements, or even other effects. And so on. Here are a couple of examples:

E-A-I: Effects can generate new Arrangements, which in turn lead to new Ideas

Effects can provoke the addition of new arrangements to an already existing and unexamined set of arrangements. We can look back on our example of the arrangement of chairs as the primary learning tool in school. Sitting all day can lead some students to practically explode out of their young bodies—whether it’s wiggling, giggling, jumping around, or even fighting.

These students who can’t sit in their chairs and stay focused on the task at hand are frequently diagnosed with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) and prescribed medication like Ritalin or Adderall. Both the diagnosis and prescription were new medical arrangements added to the set of arrangements called chairs and school. We posit that there would be no diagnosis of ADHD if there was no social situation regulating and policing attention. However, the bodies which are out of compliance with the required means of demonstrating attention are more likely to bear the burden of the situation than the situation itself. “Fixing” out of line bodies with medication is easier for the school than the work of changing the arrangements out of which the effects emerge.

Now the arrangements of ADHD and Ritalin give us new ideas about people. Now we have a new type of person, one unable to pay attention or stay still. This idea is so widespread that the term ADHD is frequently used in pop culture, including laypeople diagnosing themselves or others. Ian Hacking refers to this as “making up people,” and uses examples of new categories of people from “obese” to “genius”:

I have long been interested in classifications of people, in how they affect the people classified, and how the effects on the people in turn change the classifications. We think of many kinds of people as objects of scientific inquiry. Sometimes to control them, as prostitutes, sometimes to help them, as potential suicides. Sometimes to organise and help, but at the same time keep ourselves safe, as the poor or the homeless. Sometimes to change them for their own good and the good of the public, as the obese. Sometimes just to admire, to understand, to encourage and perhaps even to emulate, as (sometimes) geniuses. We think of these kinds of people as definite classes defined by definite properties. As we get to know more about these properties, we will be able to control, help, change, or emulate them better. But it’s not quite like that. They are moving targets because our investigations interact with them, and change them. And since they are changed, they are not quite the same kind of people as before. The target has moved. I call this the ‘looping effect’. Sometimes, our sciences create kinds of people that in a certain sense did not exist before. I call this ‘making up people’.7

A-I-E: Arrangements yield new Ideas that perpetuate Effects

Another example of arrangements giving us new ideas about people comes from the infernal arrangement of slavery. The arrangement of slavery came from ancient ideas of power and plunder in war, but the perpetuation of it in the “modern world” relied on generating new racist ideas about Africans. Indeed, well over a century after the abolition of slavery, racist ideas created by whites to justify slavery continue to be perpetuated. As Christina Sharpe wrote in her book In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, “Put another way, living in the wake [of slavery] means living in and with terror in that in much of what passes for public discourse about terror we, Black people, become the carriers of terror, terror’s embodiment, and not the primary objects of terror’s multiple enactments.”8 In other words, the racist ideas about Black people in the United States—including the idea that they are dangerous—has had the effect of making them less safe and more likely to be the targets of violence, incarceration, and even death.

So it is important to understand that I-A-E is not a formulaic route to action or linear order of events like cause and effect. It is a conceptual framework that can help us understand and act in new ways. To do so effectively requires us to keep our eyes out for its multiple variations and reconfigurations. It’s tricky.

…

In closing, now that we’ve broken down what we mean by ideas, arrangements, and effects, we want to reconnect them. As we said at the beginning:

Ideas are embedded in social arrangements.

“I’m often asked ‘Aren’t tools neutral? Isn’t it the intentions of users that matter?’ As a semi-pro brick mason, I respond: I have seven different trowels. Each evolved for a specific task… I can’t swap them out. If I forget my inch trowel and the building I’m working on has 1/4 inch joints, I’m screwed. How you use a tool isn’t totally determined—you can use a hammer to paint a barn. But you’ll do a terrible job. Tools are valenced, oriented towards certain ways of interacting with the world. Part of thinking well about technology and society is uncovering hidden valences and explaining how past development shapes a tool’s present and future uses.”9

—Political Scientist Virginia Eubanks

By using the I-A-E framework, we’re asserting that ideas exist in the material world—in our trowels and classrooms and cars—as much as they exist in our cultural and personal worlds. Therefore, part of our work is to look at how ideas and beliefs are hidden in objects and situations, as well as the impact of the ecologies produced between these objects, situations, and ourselves.

Arrangements produce effects.

“Imagine a man who is sitting in the shade of a bush near a stream. Suddenly he sees a child running by and realizes the child is in danger of falling into the stream. The man leaps from behind the bush and grabs the child. The child says, ‘You ambushed me!’ But the man replies, ‘No, I saved you.’ ”10

—Social Psychologist Mindy Thompson Fullilove

The effects of the confusion between the man and the child seem to be produced by the actions of the man, but we would argue that there’s also the bush! When the boy blames the man, it is akin to our example of the bus riders blaming each other for the smelly, noisy, overcrowded bus. Too often we focus on those who are “doing” or being “done to,” rather than notice or question the concrete arrangements—bushes, buses, trowels—that are themselves doing. These hard arrangements overlap with soft arrangements (like expectations or schedules), and these overlapping arrangements produce effects.

For those of us fighting large-scale negative effects—those that grab the headlines or make our daily lives unbearable—it is counterintuitive to turn our eyes and actions away from them. We argue not so much for turning away from effects, but for the possibilities for change that arise when we dig into the arrangements that produce them.

How do we shift our focus to arrangements? And what new opportunities for creating social change open up when we do? Through honing our abilities to sense arrangements, intervene in them, and imagine new ones, we will uncover new potential to build the world that we want.

Notes

- Michelle Alexander, “We Are Not the Resistance,” New York Times, September 21, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Design Studio for Social Intervention, “The Grill Project: Intervening in arrangements of violence,” Ideas Arrangements Effects: Systems Design and Social Justice (Colchester/New York/Port Watson: Minor Compositions, 2020), 82–85.

- Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI), “Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness (GNH) Index,” Policy and Impact, Oxford Department of International Development.

- Jan Warren-Findlow, “Weathering: Stress and Heart Disease in African American Women Living in Chicago,” Qualitative Health Research 16, no. 2 (February 2006): 221–37.

- Ian Hacking, “Making Up People,” London Review of Books 28, no. 16 (August 17, 2006.

- Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

- Virginia Eubanks, “I’m often asked ‘Aren’t tools neutral?…,’ ” Twitter, October 24, 2018.

- Lesley Green Rennis et al., “‘We Have a Situation Here!’ Using Situation Analysis for Health and Social Research,” Qualitative Research in Social Work, ed. Anne E. Fortune, William J. Reid, and Robert L. Miller Jr., 2nd ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), 192–212.

Design Studio for Social Intervention is dedicated to changing how social justice is imagined, developed, and deployed in the United States. Situated at the intersections of design practice, social justice, public art, and popular engagement, DS4SI designs and tests social interventions with and on behalf of marginalized populations, controversies, and ways of life. Founded in 2005 and based in Boston, DS4SI is a space where activists, artists, academics, and the larger public come together to imagine new approaches to social change and new solutions to complex social issues. Visit www.ds4si.org/writings/iae.