With the growth in impact investing, some questions are being asked about the legitimacy of impact investing and how accountable it is to the community. This was the subject of a recent article by Morgan Simon published in the Nonprofit Quarterly. Simon’s main concern is that “in a drive for global scale in impact investment, we will lose the voices that should matter the most—the billions of people who will be affected by social enterprises funded by our investments,” and that consequently:

- Investors and entrepreneurs may profit at the expense of communities.

- Impact will be defined by investors and entrepreneurs instead of beneficiaries.

- There will be a deficit of capital available for community owned and managed projects.

- That capacity building within communities will be lacking.

These concerns about a disconnect between impact investors and communities provide an opportunity to consider the concept of “social license to operate” (SLO), and how it can be applied to impact investing.

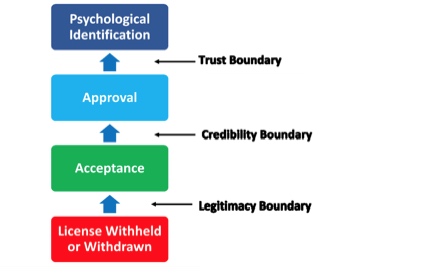

SLO has received considerable attention within the private sector, particularly within the mining industry, and refers to the level of acceptance or approval continually granted to an organization’s operations or projects by the community and other stakeholders. Essentially, SLO is about an organization’s operations or projects being granted “legitimacy,” either formally through government action or informally through community and stakeholder engagement. Its various levels are shown in the diagram below.

Earlier this year, in an article for the Foundation Center’s Glasspockets Blog, I argued that the concept of SLO is relevant to philanthropy. That’s because legitimacy is critical to philanthropy—if philanthropy is not seen to be contributing to the common good, or acts in a manner inconsistent with community expectations and norms, it will lose that legitimacy. Ultimately, that means philanthropy will stop being philanthropy.

These arguments also apply in the case of impact investing. As impact investing is motivated by a desire for the common good, and not just the private good, it will be held to a higher standard than “regular” investing. If it does not live up to these expectations, then the consequences will also be harsher.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Therefore, there must be a focus on the legitimacy granted to impact investments by the community and other stakeholders. It’s something of which every impact investor, and every organization they fund, should be conscious. Without this legitimacy, real questions can be raised about whether particular investments are beneficial or harmful, which goes to the core of why they are made in the first place.

If impact investments fund access to credit in particular communities, and the terms of these credit offerings are unilaterally altered with little or no genuine consultation or engagement with those to whom credit is granted, trust in the credit provider may quickly evaporate—resulting in a loss of legitimacy. It will be viewed as “just another credit provider,” with no real regard for the welfare of those to whom it offers credit. This will make those impact investments unviable and perhaps even harm the reputations of the impact investors more broadly.

If impact investments fund the construction of a large solar farm, but the local community doesn’t support it because they weren’t adequately engaged as part of the project, these impact investments will be compromised. How will renewable energy consumers react when they find out? Could civil society groups get involved, and campaign against the organization operating the solar farm? What seems like a worthwhile impact investment could unravel and essentially become “just an investment” because not enough attention was paid to its SLO.

Fortunately, we can expect most impact investors and the organizations they fund to be conscious of the way they act and engage. But, it’s often the case that one or two bad errors of judgment can destroy goodwill built up over time. A focus on SLO won’t address all the issues identified in Simon’s article. But what SLO does is emphasize the importance of communities and why engagement with those communities is critical to the success of an impact investment.

Engagement can take a variety of forms, but ultimately it must be about addressing the inherent power imbalance that commonly arises between investors and local communities. At one end of the spectrum, such engagement would involve consulting local communities and using their feedback to inform decision-making. In the middle of the spectrum, it could involve more directly sharing power with local communities in the decision-making process as co-designers. At the other end of the spectrum, it could involve sharing ownership with local communities—for example, through the use of cooperative structures.

One broader benefit of a focus on SLO is that by engaging with local communities more closely, a recognition and appreciation of their views and needs will filter more broadly through the impact investing community over time, making it more alert and responsive to the social and environmental issues it collectively seeks to address.