August 10, 2020; Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN)

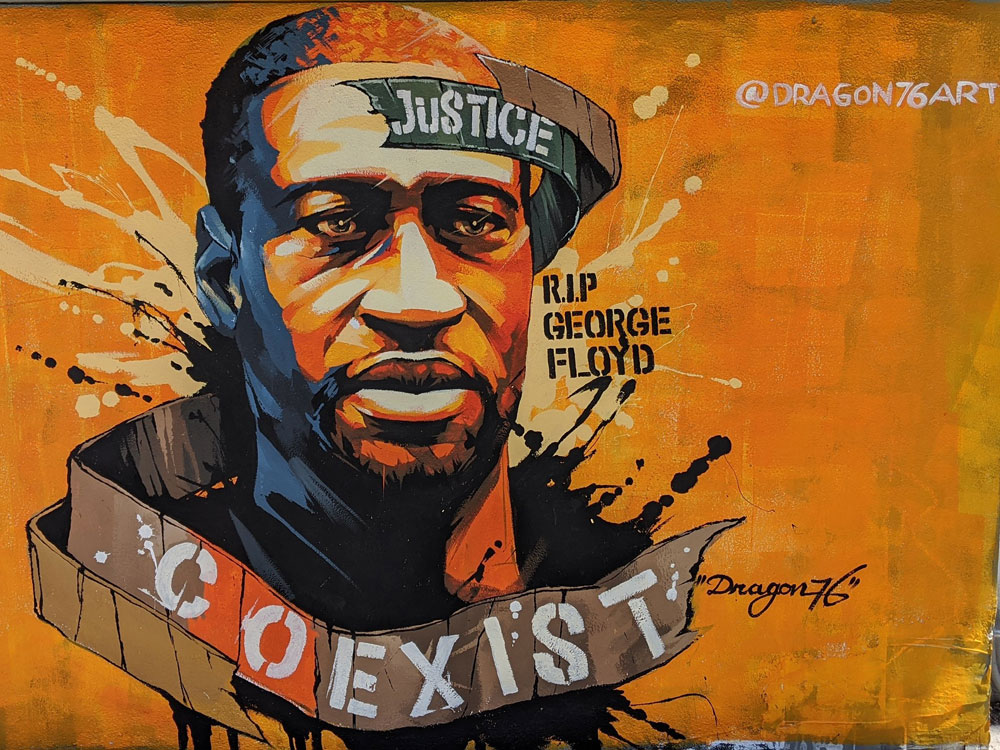

After George Floyd’s death, Anke al-Bataineh tells Jean Hopfensperger of the Star Tribune that she created a Facebook page to build a mutual aid network of neighbors directly helping people in need of things from food to finances.

“I thought, let’s see if I can connect people who live around here, maybe make sandwiches, arrange food,” al-Bataineh says. “I was thinking a couple hundred people. Within about a week, we had 16,000.”

The group, called the South Minneapolis Mutual Aid Autonomous Zone Coordination, forms part of a rising group of mutual aid networks sweeping the country. As Hopfensperger observes, “They eschew the traditional model of charity, harnessing people-to-people assistance without the hierarchy, rules, or oversight of traditional giving and receiving.”

The south Minneapolis group now has 19,700 members according to its Facebook page. The network fields requests for everything from eyeglasses and car repairs to air mattresses and coolers for tent communities to cash for families’ rents, to diapers and medicine. Hopfensperger adds that the group has grown to sufficient scale that it is now “something akin to a full-service social service agency, with mental health counselors, some medical professionals, a security team, grocery referrals, and a constant stream of requests for help and offers of aid.”

Many groups are considerably smaller, of course. The East Side Learning Center in St. Paul has 100 members, while Neighbors Helping Neighbors in Winona has more than 2,000 members. Many of the groups also combine political organizing with aid.

Mutual aid, notes Hopfensberger, has a long history. Indeed, mutual aid provided a wide range of services in US immigrant communities in the late 19th century. As Ed Whitfield, Sohnie Black, Alexandria Jonas, and Marnie Thompson wrote in NPQ this past May, mutual aid also has a long history in the Black community.

“Due to racism and segregation,” Whitfield and his coauthors recall, “many Black people pooled their money to form mutual aid clubs to help bury the dead and provide support for widows and orphans. In some cases, mutual aid groups even provided financial services that were not otherwise accessible, providing personal and business loans and even creating savings clubs to build community institutions such as churches and schools.”

This time around, mutual aid efforts are fueled by “the fears and hardships linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, widespread unemployment and growing demands to address racial inequities,” writes Hopfensberger.

“I don’t remember a time when I’ve seen so many people who care about each other stepping forward,” remarks Lawrence Shulman, a University of Buffalo dean emeritus and a longtime student of mutual aid.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“There are all kinds of crises happening right now. A crisis can bring out the best side of us, the side of us that understands our stake in the health and welfare of others,” Shulman adds.

Ini Augustine, whose family emigrated from Nigeria, finds the concept of mutual aid familiar. Growing up, she recalls, her mother and friends contributed money each month to a fund, which was then awarded to one member in need. Today, Augustine helps oversee the Midway-St. Paul Mutual Aid Autonomous Zone Coordination, a 2,000-member group that also sprang up after Floyd’s death.

“Mutual aid has been the energy of the decade,” says Augustine, a health care network engineer from St. Paul. “I did two stints in AmeriCorps, and one thing they tell you is that people have all they need within their own communities. That’s what this is about.”

The Twin Cities are not unique in seeing an explosion of mutual aid networks. Hopfensberger highlights a website called mutualhub.org, as well as a new AARP web page, both of which direct readers to a US map marked by hundreds of dots.

For organizers such as al-Bataineh, the need for mutual aid underscores “the inequalities of capitalism that are being bared right now.” Mutual aid, notes al-Bataineh, fulfills many unmet needs, while building community and breaking down barriers between haves and have-nots.

“Doing mutual aid is complicated,” al-Bataineh, a linguist who consults globally on multilingual education, points out. “It’s important that people don’t see it as receiving charity—or as themselves being a savior.”

A central principle of mutual aid groups is that network members both give and receive. As a community group in Greensboro, North Carolina, puts it, “everyone has the right to have their needs met and everyone has the responsibility to help.”

While their popularity is growing, maintaining mutual aid networks can be challenging. Volunteer burnout and donor fatigue are real challenges. But Kate Barr, CEO of Propel Nonprofits, notes that mutual aid is filling a crucial niche.

“It’s so authentic, so responsive to the immediate community,” Barr observes. “You don’t need a strategic plan. You respond to a gap in need…and the amount of aid they’re doing is mind-boggling.”

Organizers say mutual aid not only addresses community needs, but it also helps fill a void in the human heart. “I’m sad that we are experiencing so much pain,” Augustine relates to Hopfensberger. “This was trial by fire. But we’ve done it.”—Steve Dubb