October 15, 2020; New York Times

Given our focus on the nonprofit sector, we have placed much of our attention on the management practice changes that nonprofits have had to make during the pandemic. But small independent businesses have also had to pivot. The value of local small business to not just employment but community wellbeing is not to be discounted.

Indeed, as NPQ noted last month, researchers in a recent study authored by the Women’s Philanthropy Institute at the Lilly School of Philanthropy noted that many households considered their giving to include not just donations to nonprofits but support of local businesses, finding that 48.3 percent of US households participated in “indirect philanthropy during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, exceeding the portion of households who gave directly to charitable organizations.” Examples included “ordering takeout to support restaurants and their employees and continuing to pay individuals and businesses for services (e.g., haircuts, housekeeping) they could not render due to community shutdowns and social distancing requirements.”

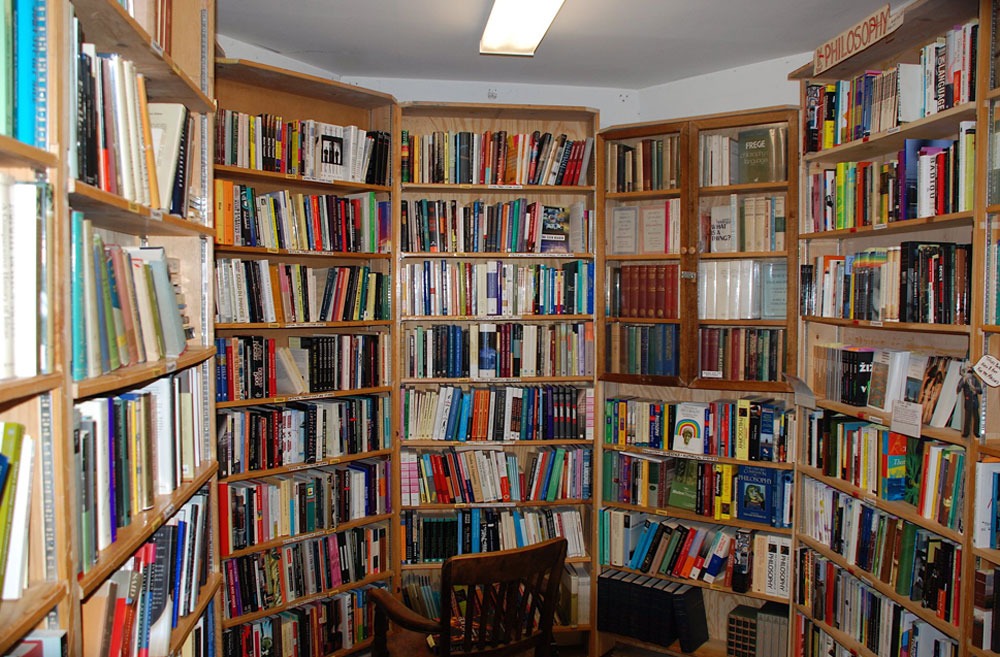

Among these community-supporting institutions are independent bookstores, which are very much under threat due to the pandemic. As Elizabeth Harris reports in the New York Times, according to the American Booksellers Association (ABA), an average of one independent bookstore a week has shut its doors since the economy shut down due to COVID-19 last March. And it could get worse: “Many of those still standing are staring down the crucial holiday season and seeing a toxic mix of higher expenses, lower sales, and enormous uncertainty,” Harris writes.

The irony is that people quarantined during the pandemic have turned to books, so market conditions overall are good. Book sales are up six percent this year compared to last year. Alas, the major beneficiary of this trend has been Amazon.

Still, independent booksellers are hardly resigned to their fate and have developed both new sales channels and messaging. For its part, ABA is distributing signs to its members to place in store windows, with messages such as “Buy books from people who want to sell books, not colonize the moon” and “If you want Amazon to be the world’s only retailer, keep shopping there.”

New sales models have also gained in popularity. “Mailing books to customers,” writes Harris, “which used to be a minuscule revenue stream for most shops, can now be more than half of a store’s income, or virtually all of it for places that are not yet open for in-person shopping.” Another common practice has been to conduct sales through curbside pickup.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Some specific examples of new forms of marketing: Avid Bookshop in the college town of Athens, Georgia, has taken to sending personalized URLs to customers with a list of handpicked recommendations. In San Francisco, Green Apple Books, which has operated in the city since 1967, has raised $20,000 selling T-shirts, hoodies, and masks that say “Stay home, read books.”

Harris notes, “Bookstores across the country face different challenges depending on any number of factors, including their local economies and how they have been affected by the coronavirus.” Still, she writes, “some broad trend lines have started to emerge.” One lesson: size matters—but in a pandemic, having less space to maintain can be a big plus. For instance, Vroman’s Bookstore, a 126-year-old store in Pasadena, California, has more than 200 employees, 20,000 square feet, and a large rent bill. It’s skating on thin ice. The store reports that sales are still down 40 percent and is hoping for a holiday sales boost to stay alive.

Others are having more success, however. Third Place Books, with three large locations in the Seattle area, is down about 20 percent for the year, according to Robert Sindelar, its managing partner. Sindelar attributes the store’s relative success to its suburban locations, which attract residents working from home.

Some specialty bookstores have even thrived. Source Booksellers, a Black-owned store in Detroit, saw its orders rise after the murder of George Floyd, as readers sought out books on racism as well as ways to support Black businesses.

Allison Hill, who heads the ABA, says the group surveyed its 1,750 members in July and got 400 responses. About a third said their sales were down 40 percent or more. But another 26 percent said their sales were flat, or even up.

Holiday season is still approaching, which is often make or break. “But this year, customers won’t be able to freely swarm the store at the last minute, so booksellers are trying to encourage early shopping,” Harris explains.

Gayle Shanks, an owner of Changing Hands Bookstore, which operates in Phoenix and Tempe, highlights the stakes: “We’re really trying to get the message out, to help customers understand that not just for bookstores but local retailers and local restaurants, if they want them to be there when the pandemic over, they have to support those businesses now.”—Steve Dubb