October 22, 2013; MSNBC

North Carolina has become “ground zero” for states trying to restrict voting rights, but it is only one of many. In a press briefing on Tuesday, titled “Leveling the Playing Field,” Judith Browne Dianis, the co-director of the Advancement Project, said that 36 states have introduced restrictive voting bills this year alone. To Browne Dianis, these states and others are working from a “playbook” that provides a “laser-like focus” on restricting the voting rights of people of color.

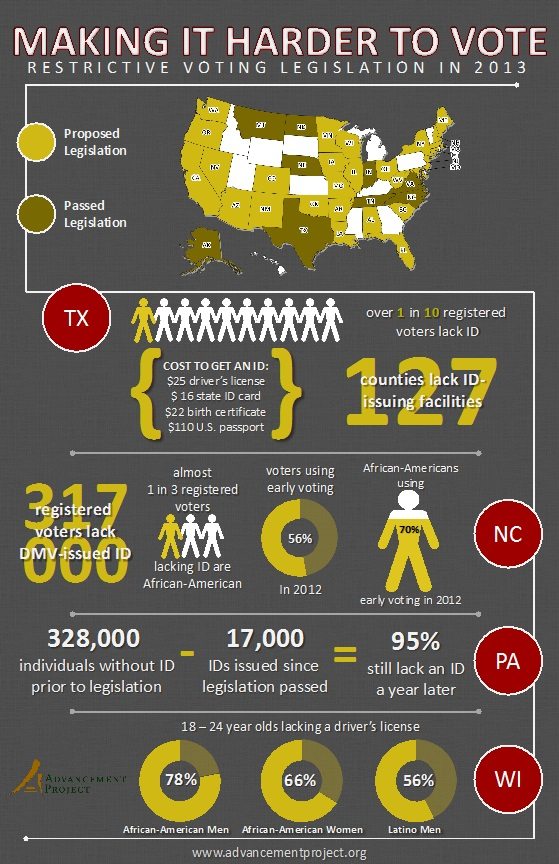

This infographic from the Advancement Project maps the states that have introduced or even passed restrictive voting legislation in 2013:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

North Carolina’s Governor Pat McCrory isn’t exactly forthcoming on why the law is needed, since voter fraud through misrepresentation at the polls is virtually nonexistent, and he has told the state’s Democratic attorney general, Roy Cooper, to keep his mouth shut about his personal opposition to the law, since as AG, he’ll have to defend the law in court. During a program aimed at attracting black voters, North Carolina black national Republican committeewoman Ada Fisher said that the North Carolina law was not a “voter suppression” law, and that the right to vote was protected in the U.S. Constitution.

Fisher is wrong: the Constitution does not guarantee the right to vote. Through various amendments to the Constitution (the 14th, 15th, 19th, 24th, and 26th), the right to vote cannot be denied to voters based on place of birth (if a naturalized citizen), race, sex, poll tax, or—if 18 or older—age. But just because states cannot deny one the right to vote based on those factors doesn’t mean that they cannot set other qualifications for the franchise. North Carolina and other states cannot use race to deny someone the right to vote, but they can try to establish other qualifications which could, in the end, reduce the likelihood of voting by people of color. According to Advancement Project co-director Penda Hair, North Carolina’s law was “written with almost surgical precision to go after voters of color,” and would be, if it survives challenges in federal court, “the worst voter suppression law in the country.”

During the press briefing, Advancement Project managing director and chief counsel Eddie Hailes noted how complex it really is to deal with these restrictive laws. According to Hailes, there are 13,000 political jurisdictions in the nation with the ability to interpret and administer voter qualifications and the right to vote. As a result, Hailes advocates an amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteeing every citizen over 18 a fundamental right to vote. Examples from the press briefing showing how frequent and diverse the state efforts have been toward voter restriction included the renewal of the voter ID law in Texas and the attempts by Florida to require eligible voters to prove anew their voter eligibility.

Suspend disbelief for the moment and assume that these voter restriction laws are not aimed at suppressing the vote of people of color. According to Penda Hair during the press briefing, in the Advancement Project’s lawsuit in North Carolina, “the data that we cite in our complaint and will be proving at trial show that every single mechanism that we challenge…hurts African-American voters more than white voters…and that data is available from official sources, including the state board of elections in North Carolina.” In North Carolina, Hair says that the new law is intentionally discriminatory, but even without that, the disparate impact on black voters is demonstrable.

Nonprofits such as the Advancement Project are crucial bulwarks in this nation’s civil rights infrastructure trying to protect the rights of people of color. If other nonprofits are concerned about mobilizing their constituents to exercise their franchise, they should be working with the civil rights sector to protect the right to vote for people of color.—Rick Cohen