December 21, 2017; NPR, “The Two-Way”

On Wednesday, two parks were freed by the City of Memphis to be sold. Both were bought by a newly convened nonprofit, and two Confederate statues in those parks came down as residents stood tearful witness.

Many in Memphis, which is 64 percent Black, agreed that in preparation for the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the killing of Martin Luther King on April 4th of next year, the two Confederate statues in the city’s parks should come down. Legally, though, the enterprise was complicated. Under the Tennessee Heritage Protection Act, the removal, relocation, or renaming of a memorial on public property is prohibited.

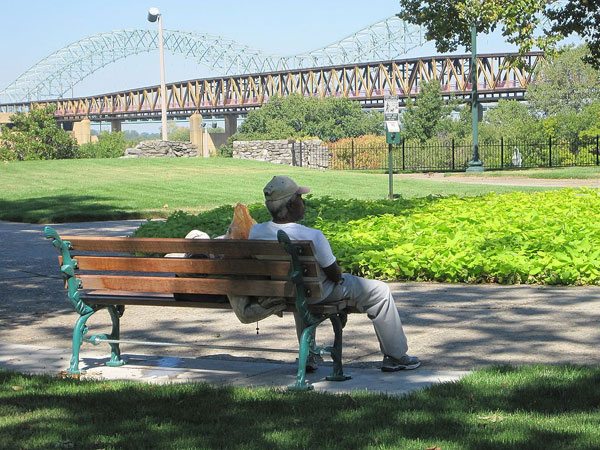

Consequently, on Wednesday, the city council voted to sell those two city parks for $1,000 each to a very new private nonprofit called Memphis Greenspace. One of the parks hosted a statue of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and the other a statue of General Nathan Bedford Forrest on horseback. The city completed the sale quickly, and those statues have now been secreted somewhere by the nonprofit, which removed them the same day the two properties were sold.

A grassroots group called Take ’em Down 901 organized for public support, and the removals had been a pre-anniversary goal of Mayor Jim Strickland for some time.

“It’s important to know why we’re here,” he wrote. “The Forrest statue was placed in 1904, as Jim Crow segregation laws were enacted. The Davis statue was placed in 1964, as the Civil Rights Movement changed our country. The statues no longer represent who we are as a modern, diverse city with momentum. As I told the Tennessee Historical Commission in October, our community wants to reserve places of reverence for those we honor.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The statue of Forrest, a Confederate general and an early member of the Ku Klux Klan, came down at 9:01 p.m. in a nod to the city’s 901 area code, and Davis followed at 10:45 or so.

“I was committed to remove the statues in a lawful way. From the beginning, we have followed state law—and tonight’s action is no different,” Strickland said. But the planning that went into Wednesday’s dramatic act of reconciliation was undertaken with speed, care, strategy, and public engagement in mind. The city council passed a law in September to allow Memphis to sell the parks for less than their market value. And Memphis Greenspace, which bought the parks and appears to exist only for the purpose of owning and caring for them, is led by Shelby County Commissioner Van Turner and only filed for incorporation in October. A popular local cause, the specialized entity has raised $250,000 from the public.

Not everyone is pleased. Republicans in the Tennessee House have called for an investigation into whether “sunshine laws” had been violated, among other things. Additionally, local grassroots advocates do not believe that their leadership on the issue has been sufficiently acknowledged. Both issues remain to be addressed.

“In the days after the August events in Charlottesville, we saw an avalanche of support come together behind our efforts,” the mayor wrote on Facebook. “In all of my life in Memphis, I’ve never seen such solidarity.”

“I feel a sense of relief,” said 63-year-old Charlene Harmon. “Finally, we can come down and really enjoy this park. And we don’t have to see something that reminds us of our painful past: the lynchings and beatings, and the selling of our forefathers.” Tami Sawyer, a leader of Take ’em Down 901, watched as the monuments toppled. “I looked Nathan Bedford in the eyes and shed a tear for my ancestors,” she said. The mayor added, “I want to say this loud and clear: Though some of our city’s past is painful, we are all in charge of our city’s future.”—Ruth McCambridge