Join us on October 20th for a webinar addressing the themes of this article. Co-author Cathy Dang will be joined by Ingrid Benedict and Isabel Sousa-Rodriguez. Register here.

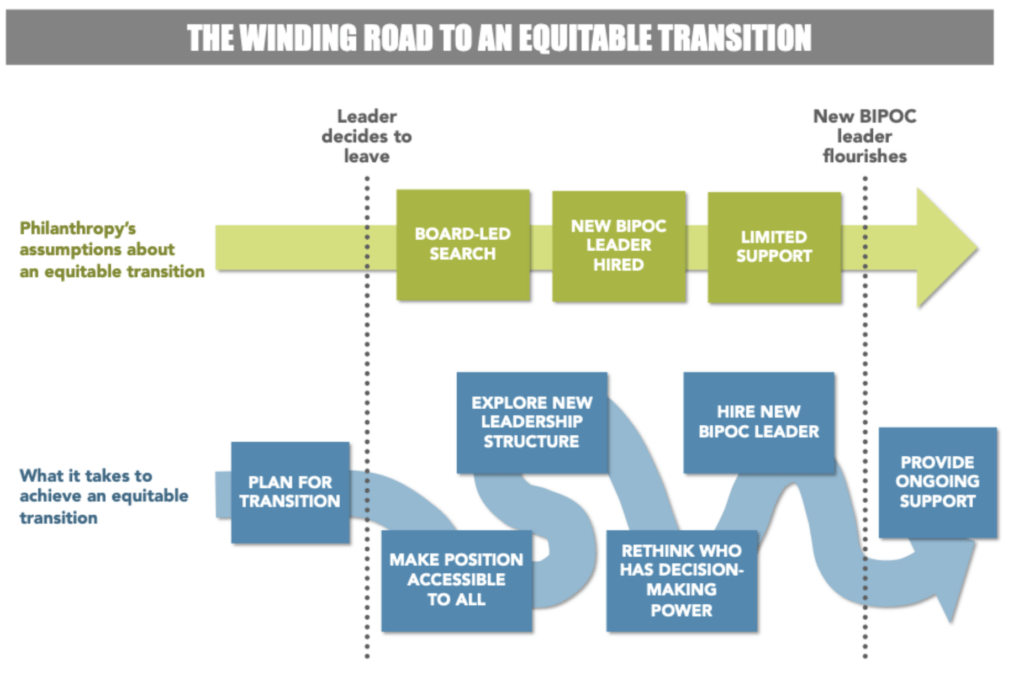

Much has been written about the wave of incoming BIPOC leadership at nonprofits and about how philanthropy needs to better support these leaders. Yet, we continue to hear that BIPOC nonprofit leaders feel under-supported and overwhelmed in their new positions. Clearly, something isn’t working.

While the general sentiment is that funders want BIPOC leaders to succeed, especially leaders who come from the communities they serve, stories continue to emerge about how these leaders have been set up to fail. Incoming BIPOC leaders often face impatience from staff to quickly get up and running, sometimes while cleaning up an organization’s inherited financial or programmatic woes. Often an organization’s first leader of color, they are frequently expected to reverse a long history of entrenched racism while serving a majority-white board. Leaders try to accomplish these Herculean tasks with little time to settle into their roles and often with meager support, especially from anxious funders.

Many experts have offered sound—but insufficient—ideas for how philanthropy can do better: provide more flexible money, build longer on ramps for transition, and embrace succession planning and transition as normal parts of an organization’s life cycle—to name a few.

We believe the problem is deeper. Poor funder behavior during transitions—whether it’s pulling back support, micro-managing, or prescribing unhelpful “best practices”—is rampant in the philanthropic sector. This behavior leaves nonprofits, especially nonprofits run by BIPOC leaders, confused, weakened, and vulnerable. It jeopardizes organizations’ visions, needs, and critical work to uplift communities.

As a former nonprofit executive director who faced these challenges and a funder who works alongside grantees during such struggles, we’ve seen and experienced harmful philanthropic behavior firsthand. Funders need to fundamentally reimagine how they think about leadership transitions to make such occurrences more equitable, supportive, and transformative for organizations.

Funders must honestly explore and shift the impact of white-dominant power structures that define what leaders look like, how organizations are structured, and who holds power. Philanthropy holds a set of harmful assumptions that show up throughout the transition process in ways that are both painfully obvious and dangerously subtle.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Who’s on deck? In the private sector, we celebrate succession planning. Leaders are expected to leave, and organizations invest time and energy in building leadership teams. But in the nonprofit world, funders have an overreliance on individual leaders. We celebrate and uplift them, and our relationships and leadership investments often stop at the C-suite. When leaders depart an organization, often no one is ready to step up and replace them because the executive pipeline has been neglected. This situation can lead to funder panic. In the worst cases, organizations fold because of a perceived inability to move forward, leaving gaping holes for underserved communities.

Boards as experts: The dominant narrative around best transition practices is that boards should take the lead. Funders reinforce this model through words and action, happily paying for consultants to work with boards on the transition process but rarely providing support for a more inclusive process where community members and staff share decision-making and input. Sometimes, communities and staff are asked for their input, but in superficial fashion—ultimately, the board will make the decision, often in opposition to community feedback. Without any real decision-making power for the community, when there isn’t alignment between the board and a community, the board’s preferences will always win. These dynamics may disenfranchise community members and devalue their perspectives. The outcome is often the hiring of a leader of color who meets the needs of the board but not of the community. While boards are legally charged with making hiring decisions, there are other stakeholders whose buy-in is critical to organizational transition and whose experience with the community’s culture and needs are often deeper than the board’s. These stakeholders should have a real say in the choice of leadership.

Hierarchy produces the best leaders: Many funders assume that one structure—usually a rigid hierarchy—fits all organizations and that hierarchical organizations are most efficient in their decision-making, but that doesn’t apply to all organizations and doesn’t develop long-term community leadership. This assumption means that organizations do not feel empowered to determine their own leadership structures to best fit their work. It also results in organizational structures that often burn out individual leaders, who hold the weight of so many decisions on their shoulders. Alternative leadership structures include co-directorship, collectives, or a leadership body led by community members—models that should be considered.

New leaders have the skill sets funders favor: When there is a vacancy at the top of an organization, philanthropy values leaders with traditional skills sets and a track record of executive experience in financial management and strategic planning. Funders also tend to trust leaders who can speak their elite language, with the use of philanthropy-friendly vocabulary and an emphasis on the written word. But this perspective does not consider the needs of an organization or community. Finding a leader whose culture, lived experience, and values match that of an organization’s community base is vital. Even if a person does not fit the traditional leadership mold, they might be best positioned to carry out an organization’s mission.

Transitions are “problems” that need a fast fix: Funders who support transitions usually emphasize the selection process as a “solution” rather than seeing succession planning and transition as a natural part of an organizational lifecycle. Instead of supporting a specific transition, funders should make consistent investments over time and include succession planning as part of their thinking on organizational strengthening. Focusing solely on the moment of transition deprives organizations of capacity development, making them less likely to succeed in the long run.

These assumptions and mindsets lead to misguided and harmful attitudes and actions. It’s time for funders to fundamentally change the way they approach transitions by centering organizations and communities. Here’s a helpful place to start:

- Ask questions: The most valuable thing you can do as a funder is to ask your grantees questions—before, during, and after a transition. This includes questions about succession planning, capacity-building outside the C-suite, community engagement during the hiring process, and how the leadership structure might evolve. All these questions signal that funders are open to listening and thinking outside the box. One of the most critical questions is what kind of support the organization needs during transition. Nonprofits may request that funders cover expenses like coaching or consultants, staff retreats, facilitated meetings of outgoing and incoming executive directors, trainings, health insurance and placement support for the outgoing ED, translations, interpretations, and even food costs for group trainings. Funding requests will vary based on organizations’ needs and complexity. Transition budget requests can be expansive, and funders should be open to all supports that an organization requires.

- Reconsider your timeline: Patience and an extended timeline are vital for successful transitions. Organizations should design transition processes that embrace the values and voices of the communities they serve—and funders need to bolster these efforts. Deeply inclusive transitions that build buy-in take time but ultimately lead to better and stronger nonprofits. Organizations must be supported before the outgoing leader leaves. The new leader requires time and support to settle into their role and build the resources they need to succeed.

- Think beyond the ED: Invest in the whole organization and its mission, not just the executive director. That means meeting with people working at different levels and in different departments and supporting their professional trajectories. This could include something as simple as inviting people in diverse roles to funder-hosted events to help them network and spotlight their work. This approach builds the capacity of the entire organization and ensures more continuity during transitions. It can also create a leadership pipeline that increases the likelihood of promotion from within when an ED leaves.

- Embrace discomfort: Transitions may result in leaders whom the community trusts but with whom donors aren’t comfortable. Sometimes, a new leader comes in with an approach that differs from that of a prior leader, causing internal tension. Discomfort is important. There is always tension with new leadership, and everyone—board, funders, staff, and community—needs to be ready for it. Funders must be prepared to extend new leaders patience and grace as they settle into their roles and sometimes make important changes. Stumbles and surprises will happen as an incoming executive director digs in. Funders must be comfortable with these unpredictable rhythms.

- Have their back: Help organizations prepare for transitions by offering every option for building a pipeline of leaders, organizational development, and transition support. A nonprofit should not worry about funding cuts in the middle of a transition; reassure the organization that funding will continue even if challenges arise. Most importantly: have honest conversations with the organization about what it needs throughout the transition process and offer information about what other organizations in similar circumstances have done.

- Look in the mirror: By nature, leadership changes are messy, non-linear, and uncomfortable processes. Funders should channel this discomfort to examine their own behaviors and consider: What do I need to change? How can I change and partner with grantees in a different way?

Sometimes, despite the best efforts of everyone involved, new leadership does not work out. Though disappointing, this need not be disruptive. An organization may require different kinds of leaders at different points in its evolution, leading to several transitions over the course of a decade. But if funders invest in the whole of an organization and its mission, these changes will feel like normal developments rather than scary surprises that jeopardize a nonprofit’s future.

Transitions are a healthy part of an organization’s evolution. It’s time that funders start acting that way by talking about and preparing for transitions alongside staff and community. This involves continual commitment to an organization’s mission and impact—and making that commitment clear through ongoing engagement and trusting dialogue.