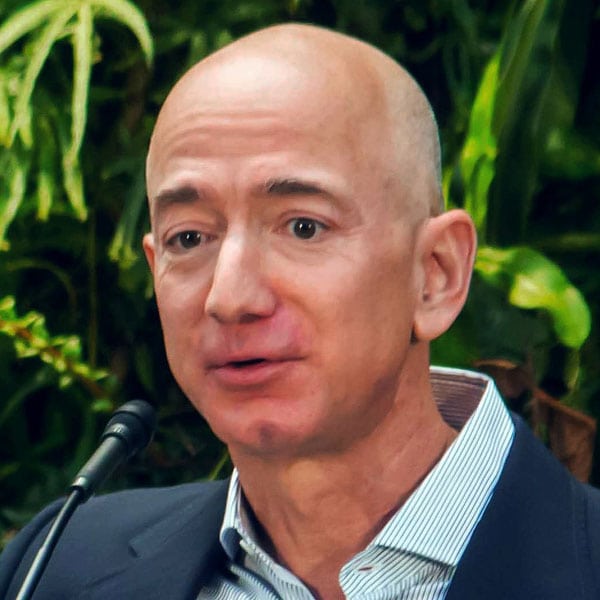

Earlier this month, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and his wife MacKenzie jumped into the philanthropic arena in a big way. They announced the formation of the Bezos Day One Fund and funded it with a $2 billion initial gift. In announcing the fund’s formation, Jeff Bezos set forth a two-pronged mission. According to Bloomberg News, the new organization will “fund existing nonprofits and issue annual awards to organizations doing ‘compassionate, needle-moving work’ to shelter and support the immediate needs of young families. The second will operate a network of high-quality, full-scholarship, Montessori-inspired preschools.”

Bezos offered a brief vision of his approach to the new venture’s entry into early childhood education, one that grows from his business success and brings opportunity and risk: “The preschools will be ‘in underserved communities’…we’ll use the same set of principles that have driven Amazon. Most important among those will be genuine, intense customer obsession. The child will be the customer.”

Having a clear mission around which the Day One Fund will focus its work is an asset, one needed by every nonprofit. But in bringing the entrepreneurial ethos that fueled his Amazon success to the work, there is a need to be cautious, as it may not transfer well to a different environment.

As a graduate of a Montessori preschool, Bezos’s desire to maximize the benefits he believes he received is understandable. But it may not be so wise to decide that this is the answer to the difficult challenge of ensuring that all children get a strong start on their education, particularly those who begin with many disadvantages, before the work begins. Listening to children and substituting his expertise for that of those in the early education field may not be a recipe for success. According to the New York Times,

Mr. Bezos’s announcement, the corporate language he used in it and the many unanswered questions it raised have made some in the education world wary. Leaders of a half-dozen prominent Montessori groups said that although they were excited by Mr. Bezos’s commitment to Montessori, they had not yet spoken to the Bezos family or their representatives, and did not know which Montessori experts, if any, were advising the project.

Montessori education is a very specific approach to teaching young children; though it has demonstrated its strengths and has many advocates, it is rooted in affluent, white communities and is only slowly moving into the communities that Bezos has targeted. Selecting it as the core for his strategy presents significant barriers to expansion.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Rebecca Pelton, president of the Montessori Accreditation Council for Teacher Education, said a key challenge would be recruiting and training enough quality teachers to staff the network’s schools. She warned against online-only teacher-training programs, which have proliferated, but may not offer hands-on student teaching experience in Montessori classrooms. Still, Dr. Pelton said, “I have faith that he’s going to do the research and ask the right questions.”

Equipping facilities to support the specific needs of this approach is expensive, with a price tag of between $30,000 and $50,000 per classroom. And convincing parents that its more developmental than academic approach to early childhood education is best is no easy task.

While the Day One Fund can use its financial clout, as mega-philanthropists like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg have, to push personal convictions into action, this may not be the most effective path to use. Faybra Hemphill, director of racial equity, curriculum, and training at City Garden Montessori School in St. Louis, told the Times that Bezos should approach the work with “radical listening and radical humility.”

Go to the communities, talk to parents, talk to children, talk to teachers and administrators and ask them: “What do you need? What are your hopes and dreams for education and for your children?” Because otherwise what will happen is that we’re doing this to the community instead of for the community.

The Bezos announcement didn’t clarify whether the intent is to work the existing network of Montessori schools or form its own schools using the Montessori approach, emulating the charter school movement as a disruptive force. In a recent NYT op-ed, Mira Debs, executive director of the Yale Education Studies, raised a strong voice of concern about Bezos taking an independent path.

Instead of creating his own network, Mr. Bezos should consider funding schools that are already doing the work he admires. Consider the 50 public Montessori programs in Puerto Rico created by Ana María García Blanco beginning in 1990, programs that are now at risk of closing because of school reorganization efforts after Hurricane Maria. Public Montessori programs could use a fund to train teachers, buy materials and build buildings…Rather than considering the children of these future schools his “customers,” albeit tuition-free customers, Mr. Bezos could orient himself toward viewing the underserved as his collaborators. Families have been organizing to create Montessori and other preschools for their children for a long time. A truly revolutionary philanthropic fund would not create a separate network, but seek out the schools, the community centers, the storefront start-ups and the other dreams in waiting.

As details of the Day One Fund’s effort begin to emerge, we will learn what the Bezos family is learning from others. If he reproduces the approach taken by the Gates Foundation and other educational reformers, there may be a lot of money invested for little benefit. There may also be unnecessary disruption as communities, attracted by the hope of new funding, reshape their early childhood education programs in line with the Fund’s wishes only to find they do not bring the promised results. Hopefully, the Day One Fund will look before it leaps.—Martin Levine