December 21, 2016; Brookings Institution

The overall unemployment rate in the U.S. has fallen to a level not seen since the Great Recession, with solid gains in the number of working Americans for the last seven years. Still, many Americans feel that the economy is not in good health and their lives are not better. A recent look at the labor market by the Brookings Institution may help us put the situation in perspective.

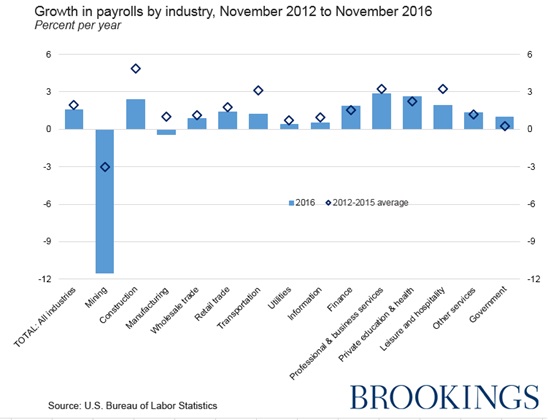

Looking solely at job creation, our economy is very strong. A stable job market requires the creation of about 100,000 new jobs every month. Since 2010, we have seen new jobs appearing well above that threshold, and so the unemployment rate has fallen. In the private sector, with the exception of a significant decline in mining jobs and a small loss of manufacturing jobs, employment has been growing across all sectors.

Government employment has seen growth, but remains about 700,000 jobs below the pre-recession numbers.

The Brookings analysis of the data shows other reasons to feel good about the economy.

The number of Americans who want full-time jobs but have been forced to take part-time positions fell 7 percent in the 12 months through November 2016. About 9 million workers who wanted a full-time job held part-time positions in the middle of 2010. That number has dropped to about 5.7 million in recent months. Similarly, the number of Americans in long spells of unemployment continues its downward path. Workers who report they were unemployed 6 months or longer fell to less than 1.9 million in November, representing a huge improvement compared with the early months of the recovery. In 2010, more than 6 million jobless workers reported they had been looking for work for 6 months or more.

Wages, too, have shown increases, albeit small ones, for the past three years.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

With all these indicators pointing up, it is surprising we don’t seem to be feeling a positive change. For many Americans, as one might see reflected in the results of the last election, the economy’s improvement has still left them behind. Too many remain on the sidelines and choose not to (or are unable to) rejoin the work force.

Despite a level of job demand that needs people who are currently not seeking work to rejoin the labor force, the November 2016 level workforce participation rate for Americans between 25 and 54 of “81.4…is still 1.5 percentage points below its level in November 2007. […] The failure of the prime-age participation rate to rebound sooner and more completely, despite improving wages and easier job finding, is one of the major mysteries of the recovery.”

A deeper look into the data shows that a significant decline in the participation rate of men is the key drag on overall job participation. Brookings posits:

Some of the long-term decline in this country is traceable to declining employer demand for relatively unskilled workers engaged in physically demanding jobs. Part of it, too, is the result of shifts in family living arrangements and in women’s role in the labor market, both of which have reduced the central role of prime-age men as the principal breadwinner of a family.

Are low wages and the lack of benefits in many of the new jobs another factor? Are jobs not located where these “labor dropouts” live? Does the problem lie in skills training and education? Yes, but there are other factors to consider. The New York Times reports that many men shun jobs traditionally performed by women. Many people have ingrained ideas of what work is or should be. A skilled laborer with 20 years of experience often can’t see themselves sitting at a desk typing at a computer screen or washing and taking care of an elderly person. More importantly, he doesn’t see such work being as fulfilling and rewarding as building or repairing things using his skills and hands.

For the new Congress and administration, figuring out how to get more people back in the job market should be central to their emerging strategy. Convincing corporations to relocate overseas jobs back to the U.S. or betting on the magic of trickle-down economics by adjusting the tax code pales in the face of this reality. Unless those who are now on the sidelines rejoin the work world, there will be not enough workers to fill future needs:

The anemic rebound in the labor force participation rate suggests the nation may not be able to find enough willing job holders. In that case, we cannot expect future job gains to continue at the pace we have seen for the past few years.

—Martin Levine