December 5, 2018; New York Post and the New York Times

“Can you do good things with bad money?”

Ilya Zaslavskiy, an Oxford-educated Russia specialist, was prompted to ask this question asked when he learned that the Hudson Institute’s Kleptocracy Initiative, an organization where he serves as a member of an advisory council, had recently accepted a $50,000 donation from a source whose fortune he saw as tainted.

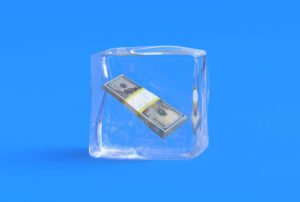

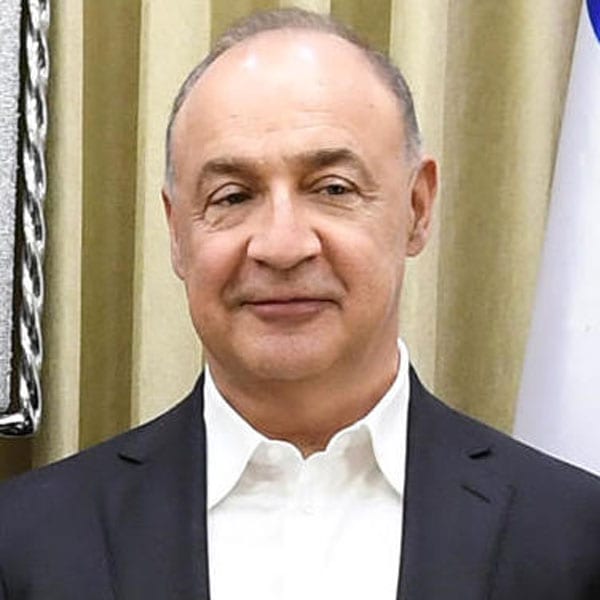

In this case, the donor in question is Len Blavatnik, who amassed his large personal fortune in the tumultuous days following the fall of the Soviet Union, when many industries were privatized and a small cadre of wealthy oligarchs emerged from the dishonest process. Ranked as the world’s 43rd-wealthiest person, with a fortune estimated to be $19.5 billion, Blavatnik left Russia and obtained both British and US citizenship. Seeking to paper over the sordid history of his fortune, he has turned to philanthropy as his channel to respectability. In addition to supporting the Hudson Institute, his family foundation has been a major donor to Oxford University ($100 million) and Harvard University’s Medical School ($250 million).

Writing in the New York Times, Ann Marlowe asked the nonprofit world to reconsider a continually difficult question—the morality of allowing Blavatnik or any other wealthy individual to donate their way to respectability: “To be clear, Mr. Blavatnik is not accused of any crimes, in the United States or in Russia. But he is undoubtedly a Kremlin insider, someone who has made an enormous fortune trading on his political connections to a deeply corrupt circle of oligarchs and a criminal Russian state.”

From Harvard University’s perspective, the good his largesse will do outweighed the legitimacy of its source. When the university announced a $200 million naming gift to the school in early November, as described by the Harvard Gazette, Harvard President Larry Bacow described the gift in glowing terms as an “unprecedented act of generosity and support.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“It’s one thing to dream for oneself, for one’s family and friends, even for one’s community,” Bacow said. “It’s another thing to dream for all people, to dream for a future in which more lives are improved and saved through the creation and application of knowledge through science.”

When the Times asked the University to comment on the ethics of the donation, the university’s response indicated that they were not having second thoughts: “Harvard Medical School is deeply grateful for the generous and transformational commitment from the Blavatnik Family Foundation that will support discovery at HMS propelling the school’s mission to transform human health.”

The Hudson Institute should be more sensitive to how Blavatnik earned his fortune. Its Kleptocracy Institute was formed to study “the corrosive threat to American democracy and national security posed by imported corruption and illicit financial flows from authoritarian regimes.” The gift was so questionable that the Institute’s founder, Charles Davidson, resigned in protest. Explaining his decision, he told the New York Post that “Russian kleptocracy has entered the donor pool of Hudson Institute…Blavatnik is precisely what the Kleptocracy Initiative is fighting against—the influence of Putin’s oligarchs on America’s political system and society—and the importation of corrupt Russian business practices and values.” Yet the Institute saw no reason not to cash the foundation’s check, saying in a statement, “The Blavatnik Family Foundation sponsored a table to our annual gala. We are grateful for all those who are supporting Hudson’s work.”

Marlowe is not the first person to ask nonprofit organizations to set a higher standard even when the need for philanthropy is great when she observes, “Accepting gifts—especially naming gifts—from people with dubious sources of funds or close ties to despotic regimes encourages the view that dirty money can be cleansed by charity. What lessons does that teach…what message does it send to citizens of countries troubled by kleptocracy and corruption?”

There is a history of this question rising to the surface after each instance of a large donor with a legal or ethical problem coming to the forefront. It was the same not too long ago when Harvey Weinstein’s depravity caused headlines. The pattern appears to be that if public outrage is not too great, the source of philanthropic giving does not matter. Is this how it should be?—Martin Levine