March 30, 2017; Des Moines Register

The key to economic wellbeing, we are told, is hard work. Economic success comes to those who strive for it and take advantage of every opportunity that comes before them. Every job, even those that pay the least, is one step upward. Last week, we were reminded just how wrong this perspective can be, especially for African Americans.

According to Valerie Wilson and Janelle Jones, writing for the Economic Policy Institute, low-wage workers, especially those of color, have been working longer and harder but seeing very little benefit for the effort. Though working hours have gone up, the economic divide between rich and poor has grown wider.

Over the last several decades, black workers have been offering more to the economy and the labor market to incredibly disappointing results in pay and unemployment. Some have argued that the disparity in wages between blacks and white is the result of white workers working longer and harder than black workers. They blame black workers for racial wage gaps, saying that they should do anything from getting more education to simply working harder. Such explanations minimize the role of racial discrimination on labor market outcomes, while perpetuating racial bias and stereotypes of black workers as unmotivated and lazy.

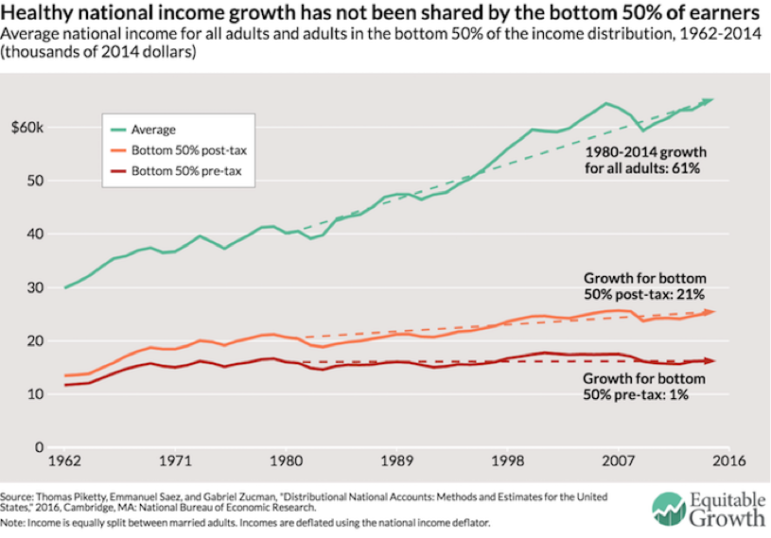

Workers who earn the least have been increasing the hours they work faster than those higher up the earnings ladder over a 36-year span (1979-2015). But working harder has not paid off. According to a just-published paper by Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, “From 1980 to 2014, average national income per adult grew by 61 percent in the U.S., yet the average pre-tax income of the bottom 50 percent of individual income earners stagnated at about $16,000 per adult after adjusting for inflation. In contrast, income skyrocketed at the top of the income distribution, rising 121 percent for the top 10 percent, 205 percent for the top one percent, and 636 percent for the top 0.001 percent.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

These results might be disturbing, but they should not be surprising. In fact, many legislators and policymakers think our labor market should be operating just this way. It has been a goal at all levels to oppose increasing the minimum wage. Last week, the governor of Iowa signed a bill that rolled back the pay of low-income Iowans. The new law, according to the Des Moines Register, “rolls back minimum wage increases already approved in five Iowa counties, including in Polk County, where the new wage of $8.75 an hour was set to take effect April 1st. Johnson, Linn, Wapello and Lee counties also have raised their minimum wages.”

The impact of this decision is not theoretical; an estimated 85,000 workers in Iowa will see their pay reduced. Among these are “29,000 workers in Iowa’s Johnson and Linn counties, who have received raises thanks to higher local minimums enacted in the last two years, will be reduced to the poverty-level federal minimum of $7.25 from $10.10 and $8.25 respectively. […] Eighty-four percent of these workers are 20 years of age or older. Nearly 60 percent work full-time. More than half are women. Thirty-one percent are parents. Almost a third are at least 40 years old. And now they face not only low pay, but pay cuts.”

At the federal level, a decision made in the last year of the Obama administration to expand the number of exempt employees eligible for overtime pay drew much opposition, including from many in the nonprofit community. A federal judge stayed the implementation of the new rule, and it’s unlikely that the Trump administration will oppose this ruling, effectively killing this effort to increase the take-home pay of as many as 4 million workers.

Workers at the bottom of the economic ladder are doing what they’ve been told they should be doing—working harder. But the math doesn’t add up: Working a standard 40-hour workweek at Iowa’s current minimum wage of $7.75 an hour ($16,120 per year) doesn’t provide a decent standard of living. What is the public policy logic of keeping salaries down to such minimal levels?—Martin Levine