September 16, 2020; Urban Institute

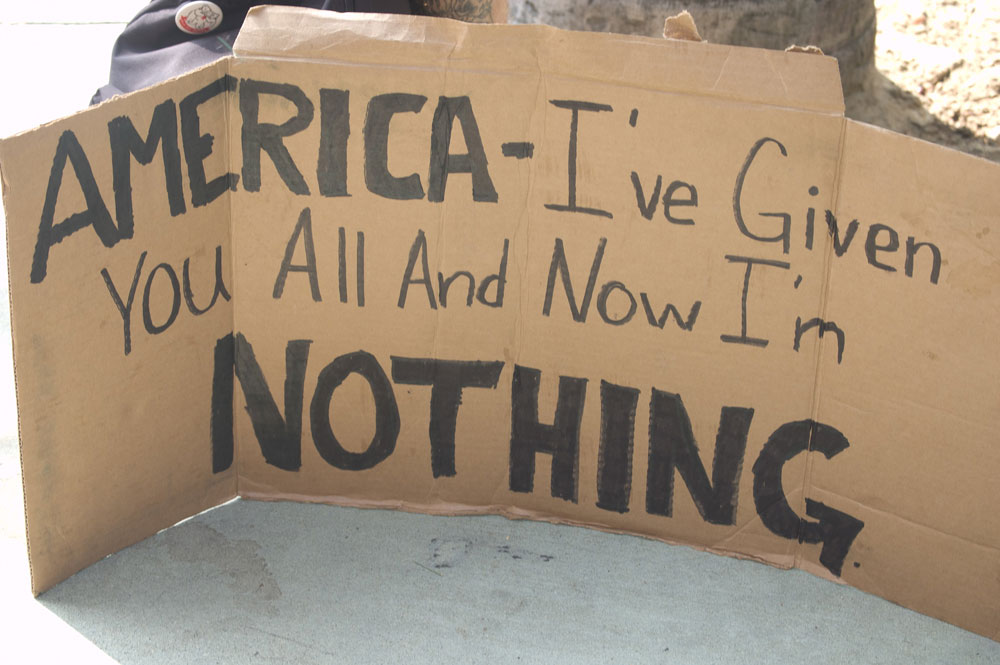

For many people in the US, being unhoused and getting caught up in the criminal justice system often seem like neighboring seats on the same abominable merry-go-round. In this vicious cycle, those who have run-ins with the law are more likely to end up homeless, and those who are homeless are more likely to have run-ins with the law. The fight to break this cycle is an opportunity for communities to redefine their values in support of individuals living on the streets. It also has everything to do with the call to defund the police.

The relationship between homelessness and incarceration is truly that of the proverbial chicken and egg: it’s nearly impossible to talk about one without addressing the other. The Urban Institute recently published several charts outlining the links between being unhoused and being entangled in the criminal justice system. To begin with, individuals experiencing homelessness are far more likely to have interactions with the police while carrying out what would otherwise be normal day-to-day activities—sleeping, sitting, and even talking to oneself. One researcher in San Francisco found that in 2018, more than 12 percent of all calls made to 311 were in regards to “homeless concerns” or “encampments.” As the budgets and responsibilities of police departments continue to grow, these calls often lead to the involvement of law enforcement, and at the worst can result in unhoused people being arrested and incarcerated, further trapping them in the cycle.

Once incarcerated, the likelihood that an individual will be homeless increases drastically. People who have been incarcerated once are seven times more likely to experience homelessness; those who have been incarcerated more than once are a staggering thirteen times more likely to experience homelessness (Prison Policy Institute). Individuals transitioning out of incarceration are less likely to have access to stable housing for a myriad of reasons, from rental policies that discriminate against those with criminal records, to family members who no longer trust a relative after they’ve served time. Unfortunately, the short-term shelters that are touted as a solution to the growing number of homeless individuals are often no solution at all. In addition to being nearly as dangerous and unpleasant as sleeping on the streets, the housing provided by shelters is rarely long-term enough for individuals to get their footing.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While the current circumstances present a grim picture of how our housing crisis feeds a deeply unjust criminal justice system, there are steps that communities can take to stand up for their homeless neighbors. In Denver, several initiatives are underway that address homelessness by limiting interactions with law enforcement and addressing the immediate needs of unhoused individuals. For example, the STAR van (short for Support Team Assisted Response) is a pilot project that seeks to give homeless neighbors the resources they need while reducing their interactions with police officers. Individuals making 911 calls related to homelessness can request the STAR van instead of law enforcement. Upon dispatch, the STAR team can provide everything from water to mental health care to a ride to a different location—all without ever involving law enforcement.

Though the program only has a short six months to prove its efficacy, the model is promising and provides a blueprint for other cities looking for ways to address their homeless population without criminalizing individuals. And even in cities where there is no current infrastructure for addressing these issues, organizers are creating guides for how the average person can stop calling the police; this small step toward community-oriented problem solving can prevent homeless individuals from getting ensnared in the cycle of incarceration and homelessness.

Addressing the issue of long-term housing is a greater challenge. Another Denver initiative, the Denver Social Impact Bond (SIB), is using funds from private and philanthropic lenders to provide long-term housing and case management services to individuals experiencing homelessness in Denver. The program was born from the realization that providing housing for individuals might be more cost-effective than the alternative: according to the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, the city of Denver spends more than $7 million per year on criminal justice and safety net programs for just 250 homeless individuals (the total homeless population in Denver is estimated at nearly 6,000). In a moment where calls to defund the police are growing ever louder, the SIB suggests that money diverted away from criminal justice could easily be used to address homelessness. By providing long-term, stable housing and other support services, communities can set individuals on a path toward success that jail sentences and overnight shelters will never provide.

These solutions being tested in Denver are in the early stages, but they provide much-needed hope that an end to the homelessness-incarceration cycle is possible. Perhaps most hopeful of all is that these solutions address the humanity of individuals who are so often overlooked and rely on drawing them back into community—reminding all of us that we are strongest when we are good neighbors.—Tessa Crisman