This article is from the Nonprofit Quarterly’s winter 2017 edition, “Advancing Critical Conversations: How to Get There from Here.”

Every leader and organization wants to make a difference. We call this mission results. BoardSource described that desire in the name of its annual survey: “Leading with Intent.” As leaders, organizations, networks, and communities, we have choices, and this article is about broadening the lens of our choices so that we can make more of a difference and speed up change for good in our world—expanding each leader’s capacity and will to lead with intent.

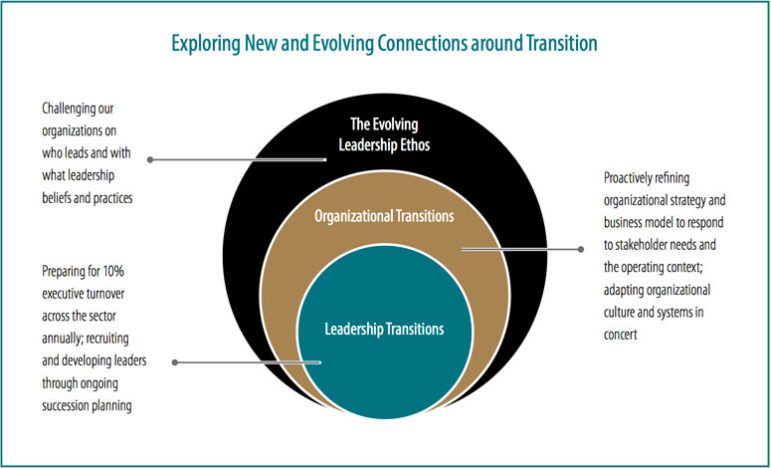

What follows will examine how what we (nonprofit leaders) believe about leading and change impacts how we traverse the unavoidable changes and transitions every organization faces. Our aim is to offer a path to connect the dots between what we broadly refer to as leadership and organizational transitions and leadership ethoses. It is our experience and conviction that mission results are better sustained and increased by intentionally paying attention to and managing well the predictable and unpredictable changes in leadership and organizations. And what we believe about who leads and how they lead influences our options and success in growing mission results over time. In this article, we will point out both what seems to work and what doesn’t.

There are reasons why not every leader and organization makes a difference. Most would like to make more of a difference; some are frustrated about it and wonder what to do. We know a lot about why some organizations get much better results than others, and we know some things about how to support boards, executives, and staffs to increase results. But we have a few barriers to overcome in order to fully use what we know, and to learn more:

- We are too often surprised and forced to act reactively to predictable organizational changes. Every executive and board leader will leave some day. Every person who adds value will, as well. What our mission is, and how we achieve it, is changing and will continue to change. Short-term success is very different from long-term sustainability and progress on mission. We deal with these and other facts of organizational life one at a time and typically only when forced to by circumstances, funders, or regulations. We are reluctant to accept that change is ubiquitous, permanent, and unavoidable, and that developing competencies in leadership and organizational changes and transitions is critical to sustaining high-performing organizations and excellent mission results.

- Leading a nonprofit organization requires passion, commitment, skills, and discipline. We are too often less than clear about the skills and discipline needed to make the most of the passion and commitment, and expect leaders to acquire these skills and discipline innately or miraculously.

- Organizations operate in a community and world with a culture and set of beliefs about leadership and who leads. There are many different views and beliefs about leadership, and these beliefs influence how well we lead, as well as our results.

Our (the authors’) experience with hundreds of organizations and research-based data make a compelling case for:

- Leaders becoming more proactive in ongoing attention to leadership and organizational transitions as a way to expand and ensure long-term mission results;

- Leaders making attention to leadership beliefs and practices (our leadership ethoses) an essential part of all transition planning, because these beliefs influence and limit or expand possible mission results; and

- Leaders—board, staff, funders, advisors, and consultants—learning continuously about the practices, disciplines, and competencies required to make the most of leadership and organizational transitions and build a culture of leader development and intentional attention to leadership beliefs and practices.

The Case for Action

In fact, there are two cases for action: what is not working and what is working. First, a look at what is not working:

- We have over twenty years of data on the predictability of executive transition and the sector’s limited attention to seeing transition as more than a search for the next leader. When key leaders leave, there is much more going on than just filling a position. Twenty to 30 percent of organizations take advantage of leadership transitions to advance mission results. Seventy to 80 percent largely miss or underuse the opportunity.

- Twenty years of talk about the racial diversity of nonprofit board and staff leadership has not increased diversity. In fact, recent data indicate that despite the stated desire by boards to expand their racial diversity, their composition has stayed the same—and the data offer little evidence that anything will change any time soon.1 Another recent study suggests that we are addressing this goal with a set of faulty assumptions.2

- Recent studies point to the need to make organizational sustainability a critical issue in annual and strategic planning and in looking at how to best increase mission results.3

In terms of what is working, there is a lot of progress that offers both hope and a guide to what competencies and disciplines have the most potential for increasing organizational results and board and staff satisfaction. What’s working is:

- Despite the complexity and generally accepted unique challenges of founder executive transitions, the combined attention to transition, sustainability, succession, and search greatly increases the odds of successful transition and sustained mission success.4

- Organizations that use trained external interim executives are able to use transition to advance organizational capacity and results.

- Organizations that engage in partnerships, collaboratives, and other types of association with others increase impact and appear to be more sustainable.5

- Organizations that go deeper in their exploration of diversity (beyond recruiting someone to that end for the board or an executive position) are able to define and build an inclusive, diverse organization and sustain and build results over time.

- Organizations that are open to shared leadership and pay attention to who leads and how each leader is supported and encouraged have an opportunity to advance internal leader development and potential succession.

If as a sector we want to speed up mission results and manage predictable and unpredictable changes better, leading with intent means: accepting that leadership and organizational changes are constant; learning how to lead and manage this change for good; and paying attention to how our beliefs about leadership may need to transform as we change direction, organizational culture and habits, and leaders.

Leadership and Organizational Transitions

For most leaders, our first reaction to possible change is to deny or avoid it. Sure, some people love change (and the churn and adrenaline that come with it), but in any board or staff or community there is typically a powerful constituency for not changing, or not changing “now.” Hence, we experience some of the challenges noted above, where we say we want something different and nothing changes.

For example, when a board hears month after month that there is a budget deficit, the focus is on the symptoms—raise more money and cut expenses. The board may accept the need to change because there is not enough operating money. In reality, the problem usually goes deeper than that. Behind the money challenge is a range of possible causes: lack of clear mission and strategy, so no compelling case to engage donors; lack of consistent results due to staffing or leadership issues; failure to see the need to change programs to better serve a new constituency. Thus, accepting that change is needed is the first step and requires a second step of making the connection between the symptom and the real problem.

In several books on change and transition, William Bridges offers some basic guidelines to leading with intent through predictable organizational challenges. Bridges’s core belief is that leaders need to appreciate the difference between change and transition. Change is an event that happens externally at a specific moment; transition is an internal psychological process that happens over time. The transition process, Bridges suggests, requires an ending or a letting go of old beliefs or behaviors and a time of uncertainty while we head into something new, which he calls the neutral zone. To complete a transition and arrive at a new beginning (new executive fully operating, new strategic plan implemented, and so forth) requires journeying through all the uncertainties of the neutral zone while completing the ending and the transition to new beginnings.6 Failure to pay attention to the transition process often undermines or derails the change effort.

When a board is faced with an executive who is leaving, there is a choice. If the challenge is perceived as finding the next executive as quickly as possible, there is little attention paid to either the ending with the outgoing executive (what needs to change, what opportunities are involved in bringing a new executive into the organization) or defining what is beginning (other than that there is a new person in the executive’s office). While this approach may seem simpler and commonsensical, it misses much of the opportunity to advance mission results when transitioning an executive.

Every change of executive happens in a broader context. Understanding this context is essential to managing the ending well, understanding your unique neutral zone (and how long it might last), and defining and heading into the new beginning with the right new leader. And this important—not necessarily long—organizational pause also provides an opportunity to review what the right leader (or leaders) means, given your changing aspirations and challenges. Executive transition is an obvious time to revisit your leadership ethos and how it impacts both the process and decisions of hiring the next executive. Pause for a moment and think about the nonprofit organizations you know. How many have experienced the following in the last few years?

- The unexpected resignation/departure of a key board or staff leader. Sometimes it happens because of a job change, new family responsibilities with children or aging parents, or (perhaps more often than we would like to admit) through sudden death.

- The expected departure of a founder or long-tenured executive, or one who turned around and transformed the organization.

- An organization whose community has changed and whose leadership has become disconnected from the community, while service demand and customer satisfaction are decreasing because of the culture and/or language disconnect.

- A board with values of diversity and inclusion that has been unsuccessful in adding board members of color who stay involved for more than a year or two.

- Suggestion by a funder or group of board members that the organization is stuck and needs to move to the next level—but not knowing what that could actually involve.

- An organization thought to be solid as a rock collapsing with the departure of some key leaders or funding.

- An organization struggling to diversify revenue and being unsuccessful in that attempt.

These are examples of how leadership and organizational transitions are happening all around us.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Leadership Beliefs and Practices—Our Leadership Ethos

The capacity of an organization to sense a needed shift in its approach to leadership is as important as ongoing readiness for the inevitable transition of leaders. The structures and processes of leadership also typically need to evolve as the organization’s mission and work evolve. We can think of this as the evolving leadership ethos of the organization.

For instance, a top-down form of leadership may have been appropriate when the founder was establishing the organization and leading it through its initial phase of maturation, but it’s likely that style of leadership will not resonate for a diverse and more broadly expert staff as the organization grows. In this case, the beliefs about what leadership should look and feel like will have changed, and the staff will likely demand more shared authority and strategic influence. For groups with explicit social change missions, their leadership ethos may include very conscious choices to experiment with shared leadership and distributed decision making, because they view their internal work as part and parcel of what they are working to achieve outside the organization. For groups that intentionally center the voices and perspectives of a particular group or population—youth-led organizations, for instance, or any group that prioritizes those most impacted by the issue they are addressing—this will necessarily impact the culture, structures, and practices of leadership in specific ways.

So, there is a leadership ethos in every organization—a set of beliefs, customs, or practices that are prevalent in how leadership is expressed—though for many organizations this ethos goes unarticulated. We believe that to fully leverage moments of organizational and leadership transition, staff and board should reflect on any shifting assumptions about leadership that may have emerged. Is there something shifting in the organization’s understanding of what’s needed from leadership? Before we hire our next executive director, for instance, do we want to consider whether we have done a good enough job at developing diverse talent inside the organization during the current executive’s tenure? Why or why not? Do we want to explore whether the board of directors wants to be in a very different kind of partnership with the staff going forward? Do we want to explore whether hiring another single executive for a job that we know is well beyond forty hours a week aligns with our values?

These are just examples of the kinds of questions that would come up at times of transition if we thought not just about who leads next but also about how we want him or her to lead going forward.

How to Get Started

This is the moment when you make a commitment or not. It is your opportunity to lead with intent. It is a decision, and a half-hearted decision will not change much. Given all the demands on your time, a half-hearted decision to “think about it” is by default a decision for the status quo and for not increasing mission results.

It is hard to make progress on building skills and disciplines without a multiyear commitment. You might not sell the rest of the board or the staff right away on making that multiyear effort, but you can start with one pressing challenge or opportunity. However, as a board leader or executive, if you begin to see this as one step toward making attention to leadership, organizational transitions, and ethos part of the organizational culture, you will significantly speed up the results and benefits. We are all disposed to the flavor or opportunity or crisis of the month. They are tempting and often all consuming. The decision to see these changing obsessions as choices in this larger context of leadership and organizational transitions makes it easier to pay attention to them or ignore them—as your plan to increase mission results dictates.

Is there a guarantee that mission results will increase if your organization gets more skilled and proactive at seeing and managing leadership and organizational change moments through the lens of a strong leadership ethos? What do you think? Think about the connections among your mission, strategy, revenue, and leadership. If you were more intentional about these connections, wouldn’t it make sense for your results to increase? Think about the beliefs and values—both stated and unstated—that guide the behaviors of your board and staff. This shapes your culture, and underneath the culture are beliefs about leadership. Is it possible these beliefs are limiting your results? Might attention to them lead to better connecting what you want to achieve with how and with whom you will achieve it?

Here are some examples of situations you might face that could bring an opportunity to make a long-term commitment and get started on a path toward more intentional leadership:

- If you are about to begin a new strategic or operational plan, call a time-out and ask how your beliefs about who leads is impacting the plan. Consider how you might improve your long-range impact and the development of your board and staff leaders with this plan.

- If you are about to nominate new leaders for the board, consider the competencies and connections needed to increase mission results, and consider recruiting for those skills and relationships. Ask leaders of an organization that is more diverse and inclusive than yours how they achieved that result, or seek help from an HR person or consultant who is skilled in deeper exploration of these issues before recruiting new members.

- If your executive has recently announced (or soon will announce) his or her departure, consider how to pay attention to the context and key issues that will influence the transition as well as the search, and get the help needed to do this. Also, look at your internal leaders and see if there are opportunities to explore shared leadership, an internal successor, or other creative approaches that serve your culture, values, and talent.

- If you have an executive who is the founder, served for ten or more years, or led a major turnaround, who may be considering departing or retiring in the next three to five years, consider focusing on how to make the most of these last years through an intentional succession and sustainability review and planning process. Consider investing in outside assistance in order to ensure a fresh look at what is possible.

- If you have had a deficit for the last three years or are facing a big shift in funding, consider calling a time-out to look at the connections among strategy, leadership, culture, and how you secure revenue, in order to develop a set of priority actions that sustain mission results within available resources.

- If your organization is large enough to have a management team, engage the team in discussion of leadership beliefs and practices, and expand your attention to leader development. If yours is a smaller organization, explore how you can best combine the talent of staff, board, and volunteers for mission results, and what shifts in leadership beliefs and behaviors will advance your team and the results.7

…

Humming organizations get and stay that way through passion, commitment, smart work, discipline, and luck or grace. We cannot influence the luck or grace. We can continue to learn more about leadership and organizational transitions and our beliefs about leadership, and use this learning to guide the day-to-day and year-to-year work of the organization. The result is greater odds of becoming or remaining a high-performing organization, and more joy and satisfaction in the time spent in the organization. It is one compelling way to speed up the change-for-good curve.

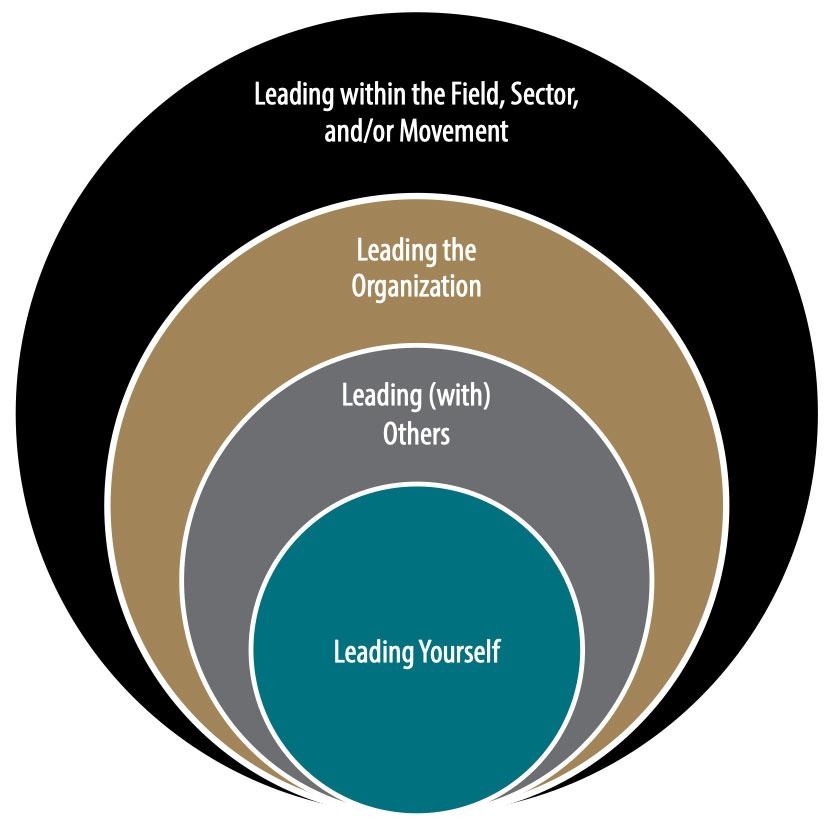

What’s Different? Leading for Mission Results

The following are examples of conscious or unconscious decisions and approaches to leading and managing a nonprofit. The first list sees leadership as managing a number of largely unconnected and episodic events in the annual and ongoing life of the organization. The second list and accompanying graphic offers a way to connect decisions into a proactive and holistic approach to leading and managing that increases mission results.

EPISODIC OR REACTIVE APPROACH

- Dealing with leadership change (executive director, board chair, board finance chair/treasurer, key managers) when it happens.

- Looking at leadership change as an isolated event—finding the next leader without attention to how the context of the organization informs requirements of leaders.

- Dealing with finances through budget and audit reviews with little connection to leadership and strategy.

- Assuming that the current beliefs and behaviors about leadership and culture will continue to work.

- Showing commitment to diversity through recruitment of one or two people of color.

- Dealing with unexpected departures of managers or board leaders when they happen.

- Assuming that there is one right approach to leading and managing regardless of organizational size, the community culture, or where the organization is in its development and organizational life cycle.

- Minimizing the importance of process and engagement through disregard of the difference between a desired change (an event) and transition (the process to get to the change).

- Relying on the leaders present and having difficulty asking for help or considering a different approach.

CONNECTED OR PROACTIVE APPROACH

- Planning for leadership change in advance, because it is predictable with review of leadership beliefs and succession planning.

- Using each leadership decision to review what is changing in how you get mission results and how the skills and relationships of new leaders might add to your capacity to improve mission results.

- Considering finances and other key systems as strategic tools to be fine-tuned to support desired mission results.

- Including discussion of leadership beliefs and culture in all planning.

- Exploring and developing a shared understanding of the values that guide the organization and how diversity and inclusiveness add value to mission results. Getting the necessary help to ensure all points of view are heard and that all are part of carrying out the values in leader recruitment, support, and mission implementation.

- Committing to defining the competencies and skills needed for leadership for mission results, assessing backup for key positions in light of the required roles and responsibilities, and developing an action plan to increase backup and decrease disruption of unplanned absences of leaders.

- Including in annual and strategic planning a broader look at how strategy and business model, leadership resources (people, money, and systems), and culture change as the organization develops, and at the implications for leadership beliefs, strategy, and culture.

- Paying attention to both the transition process and the recruitment when hiring or selecting leaders. When leading a change effort, ask what leaders are losing in the change, and make time to support the change process.

Speak up when you feel stuck or disconnected, and ask for help to regularly revisit how to best advance this mission. Consider how partnerships, collaborations, and/or other ways of working together might speed up mission results.

Notes

- Leading with Intent: 2017 National Index of Nonprofit Board Practices (Washington, DC: BoardSource, 2017), 9, 12–14.

- Sean Thomas-Breitfeld and Frances Kunreuther, Race to Lead: Confronting the Nonprofit Racial Leadership Gap (New York: Building Movement Project, 2017).

- Hez G. Norton and Deborah S. Linnell, Essential Shifts for a Thriving Nonprofit Sector (Boston: Third Sector New England, 2014), 9.

- Unpublished retrospective study of thirty transitions completed by The Foraker Group, TransitionGuides (now Raffa PC), and CompassPoint Nonprofit Services, conducted by the transition consultants involved.

- “Sustainability Model: What does sustainability really mean to a nonprofit?” The Foraker Group, accessed November 29, 2017.

- William Bridges, Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change, 3rd ed. (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2009), 3–6.

- For a summary of resources by topic, go to compasspoint.org, raffadomore.com/category/search-succession/, or search the Nonprofit Quarterly’s archive of webinars and articles at dev-npq-site.pantheonsite.io.