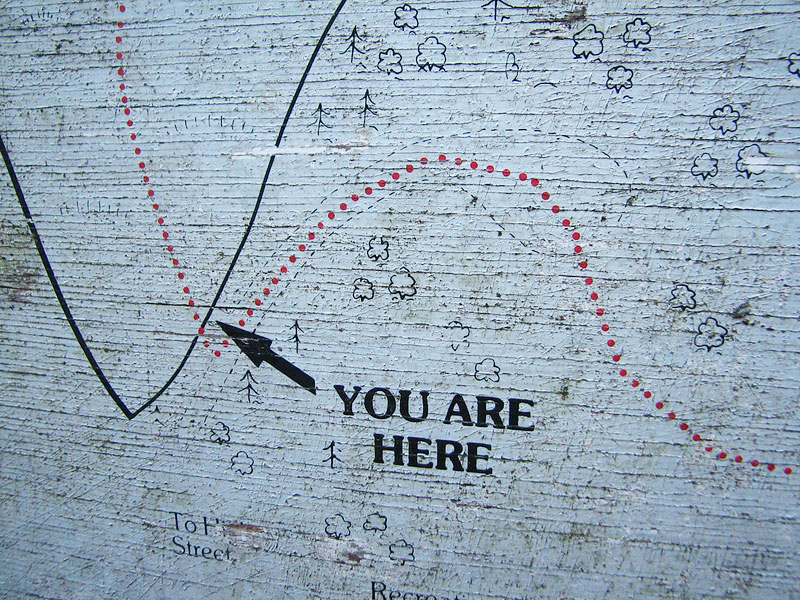

As leaders, we are naturally inclined to begin the pursuit of an important organizational goal by naming our starting place. It makes sense to us that a process roadmap should include an accurate “you are here” marker. To support us, organizational development practitioners create frameworks to use in our self-assessment. Povi-Tamu Bryant and Krystal Torres-Covarrubias recently led several hundred NPQ webinar attendees through such a framework—in this case, for locating our organizations on a six-stage continuum from exclusionary/white supremacist to equitable/anti-racist.1 Attendees whose organizations were not yet equitable, the vast majority, wanted to locate their organizations on the continuum, presumably to discern what next steps to take in their progression.

As I took in the attendees’ reactions and questions and considered my own executive, governance, and consulting experiences with numerous nonprofit organizations pursuing deeper racial equity, I reflected upon three tensions. These tensions create challenges—not insurmountable, but critical to orient around—for leaders and consultants crafting productive processes for deepening organizational equity.

To be clear, the three tensions I’ll outline are tensions that BIPOC staff and consultants—and some white staff and consultants who centered racial equity early on in their work—have been tackling for decades. Interaction Institute for Social Change, Road Map, and Change Elemental are just three examples of practitioner groups that have developed methodologies for working with and across difference in organizations and networks. What feels different about the context today is that it’s not only social movement-identified organizations that are assessing their racial justice commitment and practices; as in the broader society, a wider breadth of civil society is undertaking this work now too. So, I add these modest reflections as an offering to leaders whose organizations are currently somewhere in the midst of the transformation process.

Tension 1: There may not be one organizational location.

Some organizations are wholly white dominant or wholly equitable, but there are so many more I suspect that are, in this moment, a rather disparate collection of people and programs and systems that locate across multiple points of a racial equity continuum. In these organizations, for instance, a race equity workshop that will be enlightening to one set of staff and board will be useless, if not insulting, to another. Even a deeper, long-term consulting engagement will have to have different ways of engaging staff at various stages of their understanding and experience with anti-racist practice. Moreover, such a process will likely need to include skills-building for communicating across these staggered developmental stages, as people’s learning paths in an organization will never entirely synch up.

This reality may call for more localized assessment of leaders, teams, individual programs, and essential organizational systems such as compensation and board recruitment. Individual people, obviously, have unique lived experiences and bring to the organization their individual knowledge base and skills sets around racial equity and blind spots. Many white staff and board members bring no proximate experience of racial injustice, for instance. Many white cisgender men in positional leadership have no proximate experience of marginalization. And organizational programs and systems will locate differently on a continuum depending on when they were conceived, who has recently led them, and from how much influence by internal and external BIPOC stakeholders they have benefited.

Given the potential degree of variation in a single organization, part of our assessment as a team of leaders trying to move an organization closer to being anti-racist might include a degree-of-harm analysis. As we scan across key leaders, teams, programs, and systems,

- Which are doing the most harm to BIPOC people?

- Which are actively holding the organization back in its progress?

- Which are communicating to stakeholders that we don’t yet understand the mandate for our own transformation?

- How can we as leaders name the anti-racist intention for the whole organizational system and methodically address organizational elements in some kind of order of their urgency?

In my practice, this is what I see committed leaders doing: co-creating with their staffs and board a shared vision of their anti-racist organization and then setting about the each-by-each work of transforming key elements. To state the painfully obvious, this transformative work is intensive, and it has to be done largely as part of, not distinct from, evolving the very work of the organization itself.

Tension 2: The board, as a body, may need to catch up from the rear.

To stay with our image of a road map and the “you are here” sticker, in some historically white-led organizations, the board as a body is materially behind the staff as a body with respect to its understanding of racial equity generally, and very importantly, of how marginalization plays out in the core programs and systems of a given organization specifically. It is just true that in many, many cases, staff are closer to both the experience and consequences of the marginalization the organization perpetuates through its day-to-day work. This greater understanding by staff can be threatening to a board of directors, especially if the board members are attached to conceptualizations of a board as the primary sensemaking and direction-setting body for the organization.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Practically, how can staff and board leaders address this divide in service of the whole organizational system progressing towards anti-racism? My experience tells me to get very pragmatic here. Boards do not educate themselves and evolve on their own. Boards and staffs do not align in good time. These outcomes require intentional and intensive organizational development work. And I dare say, per my earlier suggestion that leaders conduct a degree-of-harm analysis, the board may not be the highest impact organizational element to tackle. Then again, it very well may be. This will be an organization-by-organization analysis.

For leaders who do want to close the divide, there is, I believe, a nonnegotiable ingredient. The executive director and the board chair need a partnership of trust, including the particular capacity to discuss race and power. Even if the discussions are imbalanced in terms of personal knowledge and skill, even if they are clumsy, they have to take place. I have not seen a board evolve purposefully without an executive and a board chair working together to make it happen; this feels especially true with building anti-racist perspective and ways of being on the board. In my practice, I observe executives timing what (and how much) to do with the board around race equity to when they will have a board chair with whom they can build trust.

Tension 3: Some donors and consumers may not make the trip at all.

A third tension I observe in assessing organizational equity concerns the donors and consumers who sustain an organization financially. For many organizations, a substantial percentage of financial stakeholders—be that via earned revenue or contributed support, or both—are not in alignment with them on a race equity continuum.

Consider that “liberal” foundations, corporations, major donors, and/or frequent buyers may balk at being included in an organization’s analysis of what needs to change to accelerate progress towards an anti-racist society. Is it a leader’s responsibility to confront and educate in all of these cases? Will they risk losing financial support if they do? Can we be on an authentic organizational journey toward anti-racism and not challenge our investors? I raise this because we operate in fundamental interdependence with our payors and contributors. In some real sense, we can only move so far ahead of them and expect to sustain the relationship.

In practical terms, what I observe is that just as with staff members and board members, there are some donors and consumers who are not going to make the trip with us. As our organizations become more explicit and skillful and consistent in our progress towards anti-racism, some individuals and institutions will no longer identify as stakeholders. And this has to be okay. There will be a period, likely over years, of transforming not only our organizations, but the composition of our stakeholder communities. We need to embrace this transformation and indeed, track its progress as closely as we do our own.

Thank you to Povi-Tamu Bryant and Krystal Torres-Covarrubias for their presentation of Strengthening Your Organizational Anti-Racist Practice. These reflections were inspired by that session and their wise guidance to leaders at all levels pushing organizational change.

Note

- Bryant and Torres-Covarrubias shared the “Crossroads Anti-Racist Organizational Continuum,” which is an adaptation of the “Multi-Cultural Organizational Development Continuum,” created by Bailey W. Jackson, Rita Hardiman, and Evangelina Holvino.