July 17, 2019; Vox and the New York Times

In an unprecedented move, the Louvre, the world’s largest art museum, has removed the Sackler name from the entrance to the former Sackler Wing of Oriental Antiquities. All other references to the family donations have been taped over; all references to the Sackler name have been deleted from the Louvre’s website. Given the Louvre’s heft and gravitas, will other institutions take its lead?

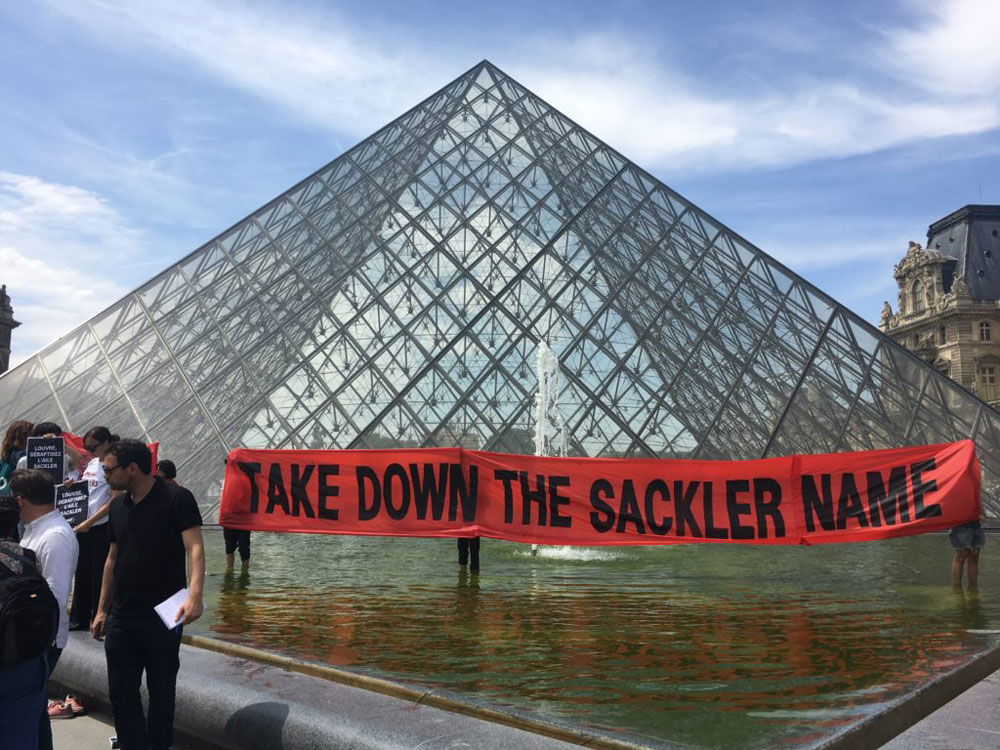

That the Louvre took the lead on erasing the name from its facilities is particularly notable because the opioid crisis is so much worse in the United States than it is in France. The Louvre had already committed to not receiving additional gifts from the family, but earlier in July, protesters from Nan Goldin’s group PAIN picketed in front of the Louvre, calling for the museum’s complete disassociation. In its statement, PAIN said, “As the most visited museum in the world, the Louvre should set an example of the irreproachable ethics by disengaging from its links to this criminal philanthropy.”

A week later, the Louvre has complied. Will others, especially here in the United States, follow? Elizabeth Harris, writing for the New York Times, doesn’t think so. Other arts institutions, like the Tate group of museums in Britain, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum of New York, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, have stopped just short of removing the Sackler name, and Harris points out a number of potential barriers to doing so. Among them are the strings that sometimes accompany these gifts in contract form. Apparently, the Louvre had the foresight to put a 20-year cap on such naming commitments, but not all do. Some, in fact, grant naming rights in perpetuity. She cites a recent instance of such a problem at the Smithsonian:

In June, Senator Jeffrey A. Merkley, Democrat of Oregon, demanded that the Smithsonian change the name of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, saying the family name “has no place in taxpayer-funded public institutions.” In a letter to Mr. Merkley, Lonnie G. Bunch III, the secretary of the Smithsonian, said the donation was made in 1982, and as was its custom at the time, the Smithsonian granted the naming rights in perpetuity.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Mr. Bunch said the gift policy was revised in 2011 and now limits naming rights to a term of 20 years or until the next significant renovation of the space.

Beyond the legal considerations, some institutions may hold off scrubbing the walls for fear of scaring off other large donors. Harris says worries over naming the living among your heroes are not exactly new.

The “damnation of memory”—as the Romans used to call it—of a generous party of the past could have a chilling effect on donors that might be concerned the history of their family, or an individual associated with them, might elicit a rebuke, said Maxwell L. Anderson, a longtime museum leader.

If someone is in an “adventurous part of the economy,” Mr. Anderson continued, like genetic engineering or bio farming, it’s difficult to know how that work is going to look in the future. Take Facebook, for example, which was a national darling just a few years ago, and is now being admonished on Capitol Hill.

Thus, fundraising meets corporate accountability, each with the need to adjust to new public expectations. How will museums resolve this ethical dilemma? One thing is certain: the public increasingly demands transparency and an end to reputation laundering.—Meredith Betz and Ruth McCambridge