If you add First Lady Michelle Obama, “Second Lady” Dr. Jill Biden, and the weight of dozens, perhaps scores of foundation grantmakers committing to address the issues involving the reintegration of veterans into civilian life, the sum is great in both weight and merit. Last week, in an event that had echoes of President Obama’s session with foundations supporting his My Brother’s Keeper initiative, this program united the foundation community behind Ms. Obama’s and Dr. Biden’s Joining Forces effort. Joining Forces is committed to raising awareness about the service, sacrifice, and needs of military families, particularly around three priority areas for national initiatives: employment, education, and wellness.

Much of Joining Forces depends on the First Lady’s bully pulpit, encouraging the public as well as institutions from all sectors of the American economy to do what they can to boost and expand jobs, education, and health services to veterans. Four days ago, Joining Forces added its leverage with the foundation community to announce the Joining Forces pledge: 30 private, institutional, and corporate foundations committed over $174 million over the next five years to veterans programs.

The foundations’ money pledge

The pledge is simultaneously impressive and somewhat limited. Getting 30 foundations to weigh in with a cumulative commitment of $36 million a year in support of returning veterans is hardly earthshaking. There are 100,000 private, corporate, and community foundations in control of north of a half trillion dollars of tax-exempt assets. The pledge amount isn’t huge—but it is significant. For many of the types of foundations making the pledge, these were uncharacteristically large commitments. Other than the Heinz Endowments, the participating foundations aren’t among the largest, and some are hardly high profile players in philanthropy. For a pledge effort that Peter Long, president of the Blue Cross Foundation of California, told us started only a month ago with an email note to their funders, $174 million in pledges is solid.

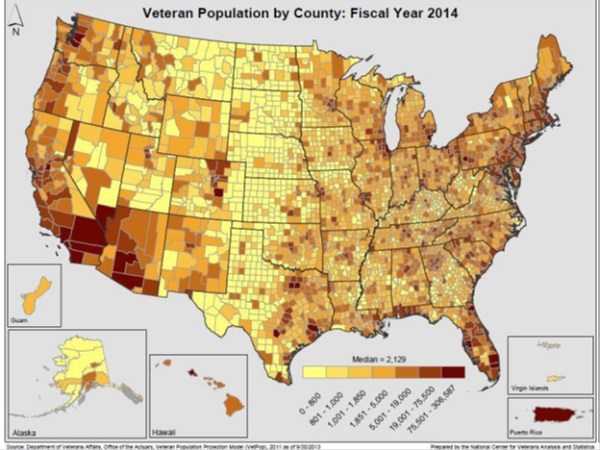

That may be part of the subtext of this initiative. Unlike the typical foundation show that trots out Gates on health or Gates and Walton on education, this one emphasizes foundations that are closer to their communities than the big national players. The “localness” of the foundation commitments is noteworthy. While many programs for veterans have been established near military bases, the current approach in the U.S. military is for a volunteer army, drawing from the Guard and Reserve in many instances. When Guard and Reserve soldiers return home, they return home to local communities, not military base centers, posing a challenge and an opportunity to local funders and service providers. The efforts of local funders, particularly community foundations, in mobilizing their resources and connecting their grantees to deliver programs and services takes on additional significance in responding to the needs of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in an increasingly volunteer military.

On the other hand, many of the big foundations, as veterans organizations know all too well, say that veterans issues are not part of their grantmaking space, even if it is patently clear that veterans are among their constituents when the fund programs in education, health, and employment. For veterans service organizations, it is good to know that foundations are putting up dollars and that the Foundation Center, as part of the COF/Joining Forces effort, is apparently committed to tracing those dollars, but the veterans charities themselves have to be let in the door to participate and not given the all-too-common refrain, “We don’t do veterans.”

A community of foundation practice

The logical follow-up question is “money for what?” A diverse collection of funders have made pledges, ranging from the Heinz Foundation and the McCormick Foundation, both making the largest pledges, to the Wounded Warriors Project, a very high-profile charity that raises plenty of dollars, runs its own programs, and on occasion makes some grants to other organizations. The First Lady’s remarks had an overtone of volunteerism, the importance of supporting organizations such as Give an Hour, and getting all Americans to volunteer somewhere and somehow for veterans.

The Obama administration has been as volunteer-focused, or stipended-volunteer-focused, as any. The government’s innovation programs have emphasized the maximization of low- or no-cost volunteers, particularly the stipended AmeriCorps members. In the Joining Forces/Council on Foundations program, Points of Light, the volunteer mobilization effort created by President George H.W. Bush, was among the central organizations in the program and seems to have been influential in the meetings that led up to this effort, something called the White Oak Steering Committee. White Oak is the name of a plantation in Yulee, Florida, historically owned by the family of Howard Gilman, a paper products manufacturer whose family foundation funded issues in conservation, the arts, and HIV/AIDS. Veterans issues could be added to this eclectic list of program priorities, due in part to the foundation’s role as host of White Oak convenings the matter, with former Gilman Foundation executive, Doug Wilson (also a former DOD Deputy Secretary for public affairs), playing a visible role.

The First Lady gave a wonderful example of positive volunteer service for veterans, an effort from Give an Hour to help veterans with mental and emotional issues by linking them to volunteer mental health providers. She noted the positive results of the specific story she told about Give an Hour in helping a young woman veteran, though that might be somewhat attributable to the fact that the Give an Hour volunteers were technically trained in the issue they were addressing; these were the mental health providers that veterans ought to have had access to, had federal and community systems operated as they should.

“We’ve got to show our veterans and military families that our country is there for them not just while they’re in uniform, but for the long haul,” Michelle Obama told the assembled funders and service providers. And the areas highlighted as key focuses of both Joining Forces and the COF veterans initiative really do take experience and expertise available over the long haul. In employment, for example, the one-day job fairs convened by a number of organizations are good information-sharing resources but do not address the long-term challenges of providing pre- and post-placement support for veterans with disabilities such as PTSD and TBI. Success in those arenas requires deep involvement that lasts for years and sometimes can be undone with inconsistent and inadequate volunteer efforts.

The answer to what should be done—and what works—may be in the substance of the program that’s more important but less showy than the announcement of nine figures in foundation funding: the Council’s Veterans Philanthropy Exchange, meant to be a networked online community of practice. It will include a resource library, mapping tools (provided by the Foundation Center), information about individual donors, best practices information, opportunities for peer-to-peer engagement and learning, and information on specific veterans-related topics such as homelessness and employment.

Our guess is that the Veterans Philanthropy Exchange is the key advancement that the Council is promoting here. Communities of practice are informal or formal gatherings of people and institutions galvanized by a common interest with the objective of gaining knowledge and sharing information and experience in their field. The Council’s Stephanie Powers has been working to launch this community of practice for a very long time and has recruited Allison Carney from the Nonprofit Roundtable of Grater Washington to be the manager of this COP. But the membership is really the key to it. Will foundations actually share? Will they do more than self-promote? Will it be more than a mechanism dominated by a few insiders? Will they take advantage of the online network to engage in real-time sharing and collaboration? Will the foundations put in real substance to make this work?

The upside could be much more funding than the $170 million in commitments announced at the Joining Forces program. But perhaps more importantly, active real-time exchanges among the foundations might help funders identify programs and services of substance and skill and get past the cacophony of organizations that claim to serve veterans but offer little of substance to move the needle.

Equally as important, however, might be to get funders in the veterans space to include real public policy advocacy in addition to support for services. It was striking in the program that with presentations from representatives of the VA, the Joint Chiefs, and the First and Second Ladies, there was scant attention to an advocacy agenda. The message one might have walked away with was that government is trying—the VA, for example, is the government’s second-largest agency, with 341,000 staff, and working with other agencies such as Health and Human Services, Labor, and the Pentagon itself—but in need of foundation help to do even more.

Maybe this couldn’t have been accomplished in the part of the program with Ms. Obama and Dr. Biden present, but there was no way that policy advocacy shouldn’t be part of the veterans’ funders community of practice, addressing opportunities such as these:

- Wiping out the backlog for veterans accessing benefits through the VA, improving and fixing the disability claims process

- Correcting whatever might be happening—or not happening—with veterans getting access to the help they need from VA hospitals

- Strengthening efforts that go after predatory for-profit institutions of higher education taking advantage of veterans benefits

- Dealing with the problem of sexual assault, which has a vast impact on women members of the military

- Strengthening the incentives for employers to hire military veterans and veterans with disabilities

- Protecting the nearly 1,000,000 veterans returning from Iraq, Afghanistan, and other foreign deployments from job discrimination at home

- Overcoming and potentially restructuring the array of federal employment and education services to veterans to make the programs more seamless and reduce or eliminate gaps

- Maintaining and increasing funding that addresses homelessness, if veterans advocates hope to see the realization of General Shinseki’s goal of eliminating veteran homelessness by 2015

- Reforming VA-funded programs administered by state agencies (such as Veterans Employment and Training Services) that should be placing veterans into sustainable jobs but often aren’t

- Making sure that the Office of Federal Contract Compliance makes the new regulations behind the Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Act strong enough to ensure that veterans, especially disabled veterans, get access to good jobs with federal contractors

The strongest stories of funders engaged in advocacy of sorts came from Nancy Jamison of San Diego Grantmakers and Don Cooke of the McCormick Foundation of Chicago. Both described foundation initiatives; in Jamison’s case, a regional grantmaker’s initiative oriented toward redesigning the array of services available to returning veterans. Both are admirable and necessary, but are difficult to draw on as easily replicable models.

For Chicago, in McCormick, you’re seeing one of the out-and-out leaders of the veterans funding world. It is difficult to remember a gathering of foundations on veterans issues that didn’t end up with Cooke in a speaking role, explaining things to others. How many other locally significant funders are willing to play the role in their communities that McCormick has played to guide efforts to rearrange the pieces on the chessboard to make the system of veterans assistance work better?

{loadmodule mod_banners,Ads for Advertisers 5}

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

For San Diego, Jamison’s story is enthralling, but limited. San Diego is probably the number-one or number-two city for returning war veterans. The fact that the regional grantmakers association and the variety of funders in the San Diego area have pulled together something as comprehensive and intensive as the San Diego Veterans Coalition and the Military Transition Support Project is impressive, but much of the need exists in areas where military and philanthropic resources are not so concentrated.

As much as any, the Iraq and Afghanistan wars have reflected the U.S. all-volunteer military posture, with repeated deployments of Guard and Reserve units. Amazingly, 37,000 service members have had five or more deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, more than a quarter of them Guard or Reserve members. As of 2012, of 1.6 million U.S. military members who served in Iraq and Afghanistan and returned home as veterans, 675,000 were from the Guard or Reserve. The challenge of identifying and reaching Guard and Reserve veterans is not to be underestimated.

The same applies to the noteworthy programs of the Robert R. McCormick Foundation, whose focus on Chicago area veterans in helping promote systems of care, capacity building for nonprofit providers, and convenings of nonprofit providers and government agencies is laudable, but dependent on the willingness of a foundation like McCormick in a big city willing to make veterans issues one of its primary areas of concentration. But outside of military concentration points like San Diego or major metropolitan areas with a committed funder, like Chicago and McCormick, much of the nation lacks any apparatus for the kind of systems design that Jamison described. The Department of Veterans Affairs map of concentrations of veterans populations makes the point visually:

The Veterans Philanthropy Exchange Community of Practice and the multi-foundation pledge are both good steps, but they have to go beyond the “usual suspects” to make sure that the advocacy and systems change demonstrated in San Diego and Chicago happen elsewhere in the nation where veterans are often more hidden, less likely to get support from the military branches, unlikely to reach out to the VA for help, and in many cases unlikely to self-identify as veterans because they were civilians before their deployments and are returning not to military bases, but to their home communities.

The fading federal role

The First Lady’s speech at the convening was nothing short of inspiring. Ms. Obama is an effective speaker and knows how to connect with an audience. Where most presenters at the event were text readers, she displayed authentic emotion in the full course of the event. But her message about Joining Forces, like all of the efforts highlighted during the event, was about reaching out to businesses, service providers, and foundations. The federal government’s role, like its function in President Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative, was hortatory, to encourage the players to do more, not to necessarily commit more on the part of government itself.

It might in truth be difficult for the Department of Veterans Affairs at this budgetary moment to ask for more resources from Congress, especially when the agency has been a troubled bureaucracy (though General Shinseki has done much to clean up the mess he inherited regarding veterans benefits processing) and recently has been hit by new charges, at first denied by the VA, that as many as 40 patients at the VA hospital in Phoenix died while on the waiting list for care at the facility. (Revelations from a whistleblower have now prompted a Senate investigation by the dogged John McCain.) Note that after the VA’s top health official, Dr. Robert Petzel, had given Congress a blanket denial that there were any signs of wrongdoing at the Phoenix facility, Shinseki quickly backtracked in light of the mounting evidence and placed the VA hospital administrator in Phoenix and two other officials on administrative leave pending a full investigation.

With no announcement of a new federal commitment to accompany the foundations’ unprecedented commitment, the federal role at the session seems to have been one of lending the First Lady and Dr. Biden to galvanize public attention and pump life into what other foundations and service providers might see as potential in this philanthropic effort. Accompanying the foundations’ pledge was the announcement of something much less concrete: Bank of America/Merrill Lynch, in partnership with Social Finance, was going to initiate a study which would be the first step toward generating approximately $15-78 million in social impact bond investment for veterans programs.

One of the Bank of America speakers, Andy Sieg, the head of the bank’s Global Wealth and Retirement Solutions section, described social impact bonds as an “emerging trend” about which the bank feels “bullish.” The emerging trend, they failed to note, comprises in the U.S. all of four social impact bond projects, according to a representative of Social Finance who spoke at a social enterprise program co-sponsored by Independent Sector and Georgetown University Law School in late April, not one of which has reached its first payment point. One of the four appears to be the private equity offering that raised $13.5 million late last year to launch a social impact bond project in a partnership between Bank of America and New York State on comprehensive reentry employment services for formerly incarcerated individuals, the programs to be delivered by the Center for Employment Opportunities.

Any number of questions arise from the Bank of America announcement. Sieg and others cited the interest of the Bank’s high net wealth clients in looking for socially relevant investments, as opposed to simply investing their assets for maximum return. But return is what the investors will get from SIBs, assuming that the projects pan out as expected and reach the expected outcomes, and BofA as the intermediary placing the investments is hardly to be expected to be without a return for the bank itself. A more significant question arises as to where the take-out for veterans SIBs will come from. If the take-out money is already there and, as the players in the Joining Forces program undoubtedly are aware, the information about “what works” is well known, why not just put those dollars to good use in support of nonprofits’ programs that need the money, rather than crafting a way for investors and intermediaries to earn extra dollars for themselves?

While the hype of social impact bonds way outstretches any of the performance to date, there’s nothing wrong with big money intermediaries like Bank of America and various promoters of SIBs such as Social Finance exploring how they might work. But as a component of a national announcement of philanthropic support for veterans services, it was a dissonant note that highlighted two things: the absence of federal financial commitment to boosting the programs that exist for helping returning veterans readjust to civilian life, and the influence of the social enterprise segment of philanthropy that needs to make a statement no matter how insignificant its track record to date and how ephemeral, in the case of social impact bonds, its promise.

Contrast the presentation of the first step in an exploration of veterans SIBs with what the foundations did with the pledge and the exchange. The foundations made concrete commitments of real money based on examples and precedents of what they have already been demonstrating, and the exchange’s community of practice will be helping connect more funders to partners and funding opportunities where their dollars can do good, right now.

Joining forces to move forward

“So if you’re watching this at any point in time, if you work with a veteran, if you worship with a military family, if there is a Gold Star classmate at your child’s school, find a way to reach out,” the First Lady said in her remarks. “Pick up a shift in the carpool. Volunteer at the VFW, or donate money to a charity that serves these families. But do something to show these families that we’re here for them, now and in the years ahead.”

It was obvious that the Joining Forces imprimatur of the Council on Foundations announcement would generate interest and impact, and the press flocked to the First Lady’s presence. But the importance of what was announced was different than Ms. Obama’s message.

One of the important takeaways from the program is the creation of a Veterans Philanthropy Exchange, which will contain white papers, 80 case studies, funding opportunities, and real-time opportunities for foundations to connect, plan, strategize, and act. Will it work? This is one of those “proof in the pudding” announcements. A new platform for a community of practice within philanthropy makes perfect sense, and one of COF’s most respected staff members, Stephanie Powers, has been behind it from the get-go, suggesting that if foundations are going to pitch in, this is the time and opportunity. But so often foundations pledging to work together don’t give as much as they could or should. The community of practice merits watching.

A second is the specific commitments made by the funders, who are in many cases the usual suspects that have been in the veterans space all along, such as McCormick, Robin Hood, Heinz, and notably Blue Shield of California, which has been responding to veterans issues beyond a narrow reading of its mission for some time. However, other funders appeared on the list of those making pledges—funders who might be less known to foundation watchers and not as consistently involved in veterans issues prior to this announcement, such as the May and Stanley Smith Charitable Trust ($17.3 million) and the Schultz Family Foundation ($20 million). Expanding the population of funders seeing veterans as an integral part of their missions is going to be essential for this initiative to have legs.

At the same time, some of the funding announcements weren’t quite from the foundation side. The Wounded Warriors Project, often seen on television with fundraising appeals, pledged to grant out $9 million over the next five years, but WWP competes in some ways with some of the groups it would be nominally supporting. Others of unusual vintage in a foundation setting were the United Way of Greater Los Angeles, committing $765,000; the Royal Foundation of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and Prince Harry, pledging $3 million for U.S. veterans programs out of $15 million committed globally for veterans programs; and the Call of Duty Endowment, with a one-year pledge of $4 million for 2014.

As much as foundations can show their mettle in making the Veterans Philanthropy Exchange a success by truly participating, the foundation sector can make money work for veterans programs in a number of ways:

- Health conversion foundations should be studying the work of the Blue Shield Foundation of California to see how the rate of suicides among veterans as well as concerns of PTSD and TBI make supporting Iraq and Afghanistan veterans returning home a public health issue that merits health foundation support, even if the arenas for the support are housing, homelessness, and jobs.

- Community foundations should be examining the work of the same already actively engaged in veterans’ programs, notably the Lincoln Community Foundation, which was identified as one of the key instigators of the effort to make coordination and systems change of services serving veterans a top concern of every community foundation, particularly those in areas where the veterans are significantly Guard and Reserve.

- Regional grantmaker associations should be studying the San Diego Grantmakers model to figure out how they can serve as facilitators and intermediaries for multi-foundation commitments to elevate programs for veterans.

- Pharmaceutical companies’ philanthropic arms should be examining the role of Bristol-Meyers Squibb Foundation, who has committed $17.5 million to this effort, to see how they can deploy their enormous resources in this arena with its health implications.

- All foundations, especially through the Exchange, should be exploring the advocacy roles they can play to spur the federal government to fix the broken elements of veterans services, to make programs such as the VA’s Veterans Rehabilitation and Employment program (VRE) work better with the nonprofit sector, and to put some muscle and teeth behind employment regulations like the Department of Labor’s Section 503 mandates for federal contractors to hire (and not discriminate against) persons with disabilities and Labor’s VEVRAA rules for hiring (and not discriminating against) protected veterans.