This is the fourth article in NPQ’s series, The Vision for Black Lives: An Economic Justice Agenda. Co-produced with the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), this series will examine the many ways that M4BL and its allies are seeking to address the economic policy challenges that lie at the intersection of the struggle for racial and economic justice.

The uprisings in the summer of 2020 led to highly localized, specific demands, and calls for budget transparency and budget justice took center stage. Previously ignored or overlooked calls to divest from systems of harm and invest in communities became ubiquitous. Everyday people dug into the processes behind their local budgets and demanded community control and self-determination.

Today, over 7,000 local authorities worldwide use [participatory budgeting] to decide budgets in various settings.

“Budgets are moral documents” is a common refrain. Deeply embedded racism and systemic inequality are clearly reflected in government budgets through the ways certain communities receive investment while others do not. Participatory budgeting, better known by its initials PB, arises as a key tool for intervention because it shifts decision-making power to communities, giving residents a direct say in where their tax dollars go.

How Participatory Budgeting Works: Nuts and Bolts

In participatory budgeting, community members decide together how public funds are allocated and spent in their communities. Its origins are deeply intertwined with economic justice. In 1989, when the PB form was first developed in Porto Alegre, Brazil, the central aim was to reduce poverty by changing how budget decisions were made. Studies in Brazil credited PB with helping reduce child mortality by nearly 20 percent.

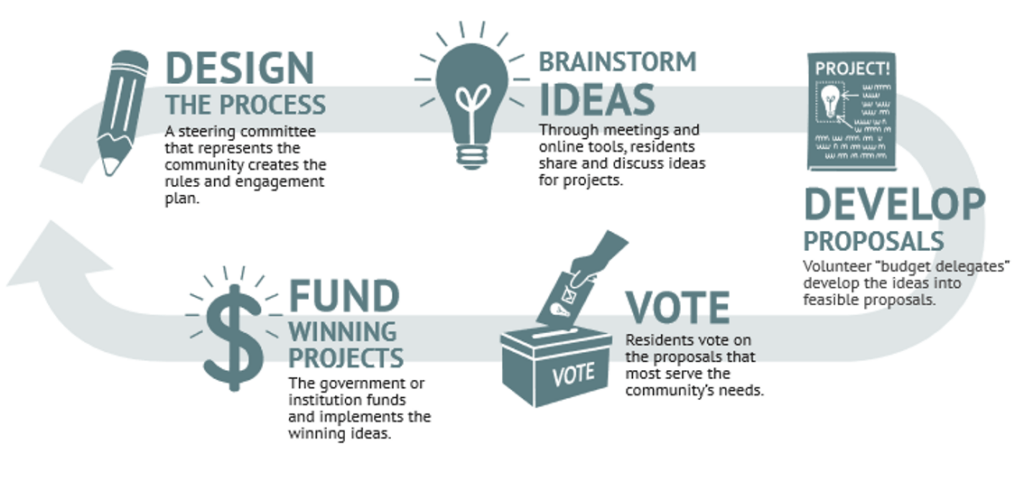

Today, over 7,000 local authorities worldwide use PB to decide budgets in various settings, from cities and counties to housing authorities and schools. The graphic below illustrates how the process works:

PB first emerged in the United States in 2009 in Chicago and is now used in over 100 US cities. It adapts to the community’s specific needs—no two communities are the same, so no two processes are the same. That said, there are five core design elements:

- Process Design

This is where a community steering committee comes together to write the rules that will govern the process. This initial rule-writing phase establishes transparency so that everyone knows what the process will look like, what their role will be, and what the process will decide. During this phase, the priorities and grounding principles for the process should also be established and codified.

- Idea Cultivation

After the rules are written, we enter the idea cultivation phase. Typically, ideas are collected through a series of community events at locations where people are, such as train stations, schools, and markets. Ideas can also be collected online through a growing number of online engagement tools.

- Proposal Refinement

Once those ideas are collected, the proposal development phase begins. This is when community volunteers work with city and agency staff to distill community-generated ideas into proposals based on need, feasibility, and impact. Those ideas are distilled into a workable plan, with associated costs. In some cases, proposals may be merged before they end up on the final ballot.

- Vote

Communities then decide which projects to support. Back in the design phase, the design committee established logistics such as vote duration, voter eligibility, and outreach plans. One primary goal is to make sure that everyone in the community is given an opportunity to have their voice heard and cast a vote on a project they would like to see funded. The projects that receive the most votes get funded.

- Implementation and Evaluation

Last but not least, it is time to implement the selected projects—and evaluate the process with the grounding from the design phase in mind. It is also important to keep the community updated regarding implementation timelines and evaluation findings, and prepare to start the next PB allocation round.

Achieving transformative change requires altering governance structures and building power.

Complexities of Implementation

Of course, engagement processes may make community members feel good, even as they fail to lead to meaningful change. Put simply, participatory budgeting creates a possible path to budget justice and community-led decision-making. But success in this area isn’t automatic. Achieving transformative change requires altering governance structures and building power.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Political scientist Celina Su defines budget justice as “public budgets that give historically marginalized communities resources to address their needs.” Su goes on to describe PB as a “node in a larger ecosystem of participation and mobilization for budget justice.” Whether PB is an effective tool in this direction must be tested, not assumed. Ensuring that PB acts as a mechanism of liberation requires regular evaluation, iteration, and equity-focused design.

If these principles are taken to heart, then PB can serve as an integral piece of a broader movement for economic justice, self-determination, and ultimately, liberation.

What Does Repair Look Like?

PB is a tool in a larger tool belt of dismantling economic oppression and building a liberated future. One example is the city of Los Angeles’ pilot PB program, LA REPAIR, which stands for Los Angeles Reforms for Equity and Public Acknowledgment of Institutional Racism.

Through this program, community residents, using a PB process, will make binding decisions to allocate $8.5 million in nine neighborhoods. The so-called “REPAIR Zones” are neighborhoods most impacted by institutional racism and economic injustice, as identified by the city’s Civil + Human Rights and Equity Department. In each zone, at least 87 percent of residents identify as BIPOC and at least 16 percent of residents are living below the poverty line.

The nonprofit I work for, the Participatory Budgeting Project, is supporting local partners on LA REPAIR. In this instance, the pilot program is intentionally focused on key neighborhoods, centers a need for acknowledgment of institutional racism, and is only one piece of a liberatory framework that mandates those closest to the issues must be closest to the levers of decision-making.

The Los Angeles effort, clearly, has major limitations. As one leader pointed out to local writer Piper French in Noēma, the $775,000 allocated to the Boyle Heights neighborhood, a quickly gentrifying area where economic disparities are in stark relief, is barely enough to buy a house there. The scope and scale of PB in this case do not match the lofty goals set forth by the REPAIR mandate.

A strong, intentional, and equity-focused design phase is…critical to setting the stage by designing with not for participants.

However, the community-based process of PB provides a strong opening for community organizing. As French herself concludes, even modest investment had helped strengthen the community fabric and set up the groundwork for an increased scope for community-based resource allocation decisions in future years.

Challenges and Opportunities

Often when we talk about opportunities for public engagement—be it on housing development, police spending, or any project proposals—BIPOC communities recognize that these spaces are not built for us. Recent research confirms this. Local government and zoning decisions often favor people who are White and wealthy, as a recent book published by three Massachusetts-based professors titled Hometown Inequality demonstrates. This pattern not only recreates but strengthens existing oppressive structures by seemingly fulfilling well-intentioned criteria and metrics for equity and engagement without shifting power.

An example of this can be seen in the American Rescue Plan Act’s inclusion of a reporting requirement for “community engagement,” which stops just short of true engagement by defining it as input and feedback rather than community control with opportunities for engagement at all steps of the process. (Sherry Arnstein’s classic ladder of participation graphically illustrates the difference.) While some municipalities (like Grand Rapids, MI) and school districts (like Central Falls, RI) seized upon this opportunity to engage their communities in PB processes, countless others have seen ARPA “engagement” come and go with surveys and ticked boxes.

Of course, PB is not exempt from these challenges. However, its core principles seek to combat them preemptively. A strong, intentional, and equity-focused design phase is therefore critical to setting the stage by designing with not for participants. Additionally, evaluation and iteration is critical, to make sure that PB does not fall into a novelty trap rather than representing a fundamental shift in status quo, and to make sure that evaluation elements have an opportunity to be incorporated and built upon by community wisdom.

Community control requires a radical reimagination of democracy—of how decisions are made and how impact is measured. PB offers a framework where real decisions over real money create real impact—not just in what gets funded, but in how community members relate to and wield public power.