July 13, 2018; WGBH

The National Park Service’s website for Faneuil Hall calls the meeting place, which opened in 1743, “The Cradle of Liberty.” The Park Service’s website goes on to explain that, “For 275 years, Faneuil Hall remains a site of meetings, protests, and debate right up to this very day. Because Revolutionary-era meetings and protests took place so frequently at the hall, successive generations continued to gather at the Hall in their own struggles over the meaning and legacy of American liberty. Abolitionists, women’s suffragists, and labor unionists name just the largest of groups who have held protests, meetings, and debates at Faneuil Hall.”

Yet, as the Park Service itself recognizes, dollars earned through the sale of slaves helped finance Faneuil Hall. “There is some irony to be found,” writes the Park Service, “because a portion of the money used to fund ‘The Cradle of Liberty’ came directly from the profits of the slave trade.” Peter Faneuil himself enslaved five people, valued at £620, an amount that is more than 45 times the average annual income earned in Boston at the time. This does not include Faneuil’s active involvement in the slave trade, from which he further profited.

To acknowledge this aspect of Faneuil Hall’s history, the city of Boston “is considering a proposal for a memorial at Faneuil Hall that would recognize the victims of the slave trade and acknowledge that Peter Faneuil, the 18th-century merchant and slaveholder who is the hall’s namesake, derived his family wealth from slavery,” reports Amanda McGowan for WGBH.

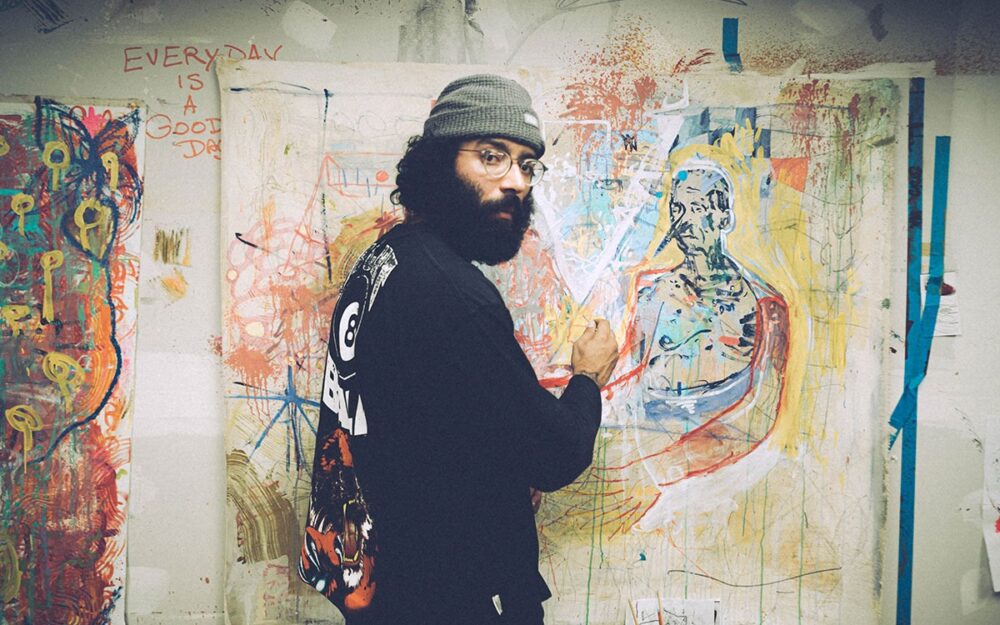

The memorial is designed by artist and MassArt professor Steven Locke. Locke’s proposed design, notes McGowan, “would take the shape of an auction block, with a small rectangle representing the auctioneer and a larger rectangle representing the people sold into slavery. The larger section would consist of a 10-by-16-foot bronze plate embedded in the surrounding brick depicting a map of the triangular trade route, which carried enslaved people, goods, and raw materials between Africa and the Americas.”

“It’s my job as an artist to walk around this city and think about resilience and racial equity,” Locke observes. “So when I walk around Faneuil Hall, I’m trained to notice what’s missing, and what’s missing is an acknowledgment of the enslaved Africans and African Americans whose trafficking financed the building of Faneuil Hall.”

McGowan adds that, “The bronze plate would be constantly heated to 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit to evoke the human beings who were bought and sold in Boston, including at Merchants Row.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“This will make touching the work an intimate and reverent experience as if you are touching a living person,” Locke says.

Boston Mayor Marty Walsh has praised the design and says he hopes it will spark conversations about Boston’s history.

“Enslaving people in 17th/18th-century Boston was not unusual,” notes the Park Service, Last month, Katharine Seelye, writing in the New York Times, pointed out that,

the trans-Atlantic slave trade played an integral role in the economy of colonial New England. The first slave ship to reach Boston arrived in 1638, when colonists traded Native Americans who had been captured in battle for enslaved Africans.

Merchants who grew wealthy from the slave trade founded and endowed several Ivy League colleges, some of which have distanced themselves from these legacies in the last 15 years or so. In 2016, Harvard Law School dropped its official seal because it featured the family crest of prominent slaveholders.

In some cases, names have been changed to redress past wrongs. For example, this past April, the City of Boston, responding to a request from the Boston Red Sox, renamed a street near Fenway Park because the street’s previous name had honored a former Red Sox team owner who “oversaw the 12-season stretch from 1947–1958 in which the Red Sox watched every other team in Major League Baseball integrate before they became the last club to do so in 1959.” In June, Seelye notes, Kevin Peterson, executive director of the New Democracy Coalition. suggested renaming Faneuil Hall after Crispus Attucks, a Black man killed in the Boston Massacre—the first casualty of what would become the American Revolution.

Locke, the artist, prefers to keep the name as is while telling a fuller story. “I understand people are wounded by the notion that a huge edifice in the city is named after a slaver. I understand the wound,” says Locke. “But I also know you can never have too much truth, and the goal is to have as much truth as possible.”—Steve Dubb