July 21, 2017; Seven Days, Los Angeles Times, and Business Insider

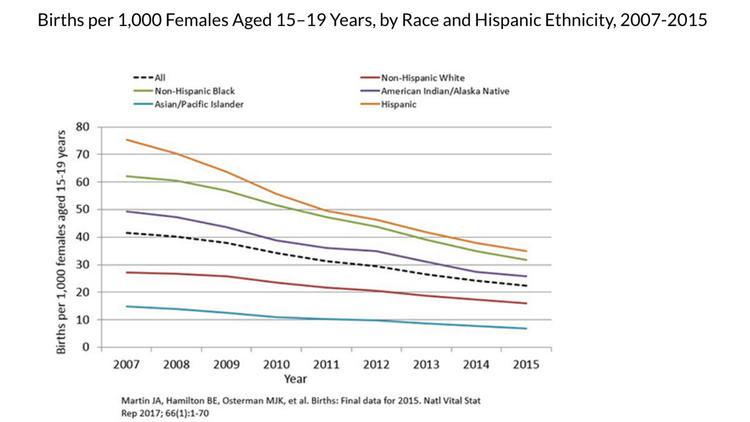

Many programs that work in prevention face a Catch-22: How do you measure success when something doesn’t happen? But this is not the case with programs that work to prevent teen pregnancies. Data on the number of women under the age of 20 who give birth have been carefully collected over the years. The data from 2007 to 2015 paint a success story of teen birthrates falling across all ethnicities and socio-economic sectors. According to Business Insider:

In the U.S., one in 19 girls gets pregnant before her 20th birthday—a number that is much higher than most other industrialized countries. The teen pregnancy rate, now at historic lows, has declined considerably over the last three decades, mostly as more young women have started using contraceptives and, to a lesser degree, waited to start having sex.

Despite this success, the Trump administration has quietly cut nearly $214 million in grants to pregnancy prevention programs across the nation. Eliminating the funds for prevention programs isn’t only bad social policy; it’s also bad fiscal policy. Adam Thomas of Georgetown University showed in 2012 that such programs pay for themselves many times over. Every dollar spent returned from $2.50 (for evidence-based teen pregnancy interventions) to $5.60 (for expanded access to Medicaid family planning services).

In digging for causes for this action beyond Trump administration campaign promises, grant recipients and others point to three recent appointments to the Department of Health and Human Services:

- Charmaine Yoest, the former head of a prominent anti-abortion group who is now assistant secretary for public affairs at the Department of Health and Human Services

- Teresa Manning, a former lobbyist for the National Right to Life Committee and legislative analyst for the Family Research Council who is deputy assistant secretary for population affairs

- Valerie Huber, the former president of Ascend, a Washington group that advocates for abstinence-only sex education, who is chief of staff to the assistant secretary for health

With these appointments, the Department that oversees these grants seems poised to push “abstinence-only” programs, which have been proven ineffective compared with programs that are being cut.

Reveal, the site for the Center for Investigative Reporting, obtained copies of the grant letters that the program organizers receive every year: This year, the letters also included a line saying the grant money would stop coming on June 30, 2018—two years earlier than the Obama administration had intended.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

An HHS spokesperson confirmed the cuts in funding to Reveal but did not elaborate on the reasons for doing so. That said, some of the organizations receiving the grants said they were told that the move was brought forward by Valerie Huber, who favors abstinence-only education instead of sexual health awareness.

Whatever the reasoning, the impact was immediate for many of the more than 80 programs that provide successful teen pregnancy prevention programs to the populations with the most vulnerability in this area. While some will have their grants continue through 2018, for many, their funds end with the letter they received on July 5th.

Some of the notices were chilly indeed. “Due to changes in program priorities, it has been determined that it is in the best interest of the federal government to no longer continue [your] funding,” read a July 5th letter sent to Meagan Downey, the head of Vermont-based Youth Catalytics, which has been coordinating a project involving Children’s Hospital of L.A. and four other institutions, including the University of Michigan and the University of Massachusetts. She says the notice blindsided her, because as recently as last month the program had been praised by federal officials.

“There’s been no substantive change in the federal government’s ‘best interest,’” Downey told the Los Angeles Times. “The only thing that has changed is the appointment of some very extreme, misinformed appointees in HHS.”

As these programs begin to rethink how and if they can continue to provide proven, evidence-based teen pregnancy prevention programs, there is a glimmer of hope.

“We’d been expecting that funding could be cut,” says Luanne Rohrbach of the Keck School of Medicine at USC, which is in the third year of a $10-million grant to provide educational outreach to as many as 20,000 teens in South Los Angeles and Compton who are at risk for unintended pregnancies. “But we didn’t think it would happen this way, and expected that there would be discussion about it. We thought there would be an opportunity at least for the program to be deliberated.”

That deliberation may come via Congressional action on the budget. This cut is part of President Trump’s budget proposal—and that word “proposal” is important. As long as this budget has not been enacted by Congress, there is the hope that senators and representatives can be lobbied and convinced of the value, both economic and social, of the current prevention programs. The futures of many young women may rest with their decisions.—Carole Levine