September 16, 2017; Guardian

Readers will recall we recently published excerpts from a letter written by Darren Walker of the Ford Foundation which advances the prospect that if this country is unable to acknowledge its past, a future free from systemic and embedded racism will be almost impossible. In that light, this Montgomery museum takes on a significance that could not be more important in the moment.

In February 2015, the Equal Justice Institute, a nonprofit founded and led by activist and author Bryan Stevenson, released “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror,” a report that documented more than 4,000 lynchings of black people between 1877 and 1950. This report and one published by Stevenson two years earlier, “Slavery in America,” have become the basis for what will soon be a museum and memorial designed to document this history.

The museum itself is being called “From Enslavement to Incarceration.” It will be housed in a 11,000-square-foot facility “at the site of a building that once warehoused enslaved people before they could be sold at auction in the town square.” It is expected to open next year.

Construction began in April 2017. The museum aims to “trace the untoward history of racial capital through generations and simultaneously shine a light on the legacy of US racial terrorism.” Already, Stevenson’s organization has created a virtual museum that allows users to explore the history of lynching in America, which NPQ profiled this past June.

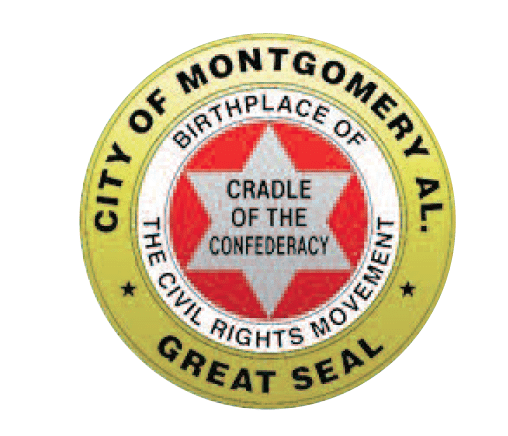

Montgomery has a complicated, contradictory, and contentious history, as Guardian reporter Jamiles Lartey relates. Indeed, Lartey points out, one does not have to go farther than the official city seal above to see the contested historical ground on which the city stands. Lartey notes that this juxtaposition of the Confederacy and the Civil Rights Movement applies to far more that the city seal. As Larety writes,

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

It was at the statehouse in Montgomery that Jefferson Davis was first inaugurated as the president of the Confederacy in a bid to preserve the institution of slavery and in defense of the inferiority of the black race. It was here too, nearly a century later, that Rosa Parks famously refused to give up her seat, and a young Martin Luther King launched his first direct action campaign: The Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Lartey relates the deep impact that the slave trade had on Montgomery: “By 1860, warehouses, slave depots, and slave pens had sprung up all over the city of Montgomery.” Stevenson observes that at the dawn of the Civil War, Montgomery “had more slave pens, depots and warehouses than banks, hotels or commercial establishments.”

Lartey adds:

That’s part of the legacy Stevenson hopes the museum can capture, ushering visitors through a dungeon-type space populated with holographic apparitions of enslaved people awaiting sale. Guests will hear readings of real slave narratives by those caught in this purgatory before moving into a space that redirects their attention to the racial terrorism of lynching that pervaded the decades after the civil war and reconstruction.

The museum will also connect to a “second site being developed a few blocks away as a six-acre national lynching memorial slated to open in mid-2018. The memorial will honor the lives of more than 4,000 black Americans lynched from 1877 to 1950, whose names will be engraved on duplicate sets of more than 800 columns, two for each county in the U.S. where a lynching was recorded.” A rendering is below:

For each county, one of the twin columns being built will stand at the memorial in Montgomery. Project organizers are asking that counties claim their columns and install them as historical markers at original lynching sites. According to the Equal Justice Institute’s detailed research, roughly one in four U.S. counties has a history of at least one lynching between 1877—the official end of the post-Civil War Reconstruction period—and 1950.

For each county, one of the twin columns being built will stand at the memorial in Montgomery. Project organizers are asking that counties claim their columns and install them as historical markers at original lynching sites. According to the Equal Justice Institute’s detailed research, roughly one in four U.S. counties has a history of at least one lynching between 1877—the official end of the post-Civil War Reconstruction period—and 1950.

Stevenson observes, “There are 59 markers and monuments to the Confederacy in [Montgomery], but yet a few years ago you couldn’t find hardly a word about slavery.” Stevenson said he drew inspiration for the museum launch from the Apartheid Museum in South Africa. Stevenson has also noted that likewise Rwanda and Germany have cultural institutions that address their violent histories.

“I do think our nation is a nation that needs truth and reconciliation,” Stevenson said to the Guardian. Stevenson added, however, that, in his view, the light of truth must shine first in order that honest reconciliation might follow.—Steve Dubb