February 19, 2019; Teen Vogue

As we noted recently in NPQ, “Museums, as repositories of historical artifacts, contain interpretations of culture, history, and the natural world, traditionally through the lens of the monied class.” As such, they often reinforce dominant narratives and cultural perceptions with “authority” and “gravitas.”

Of course, many are seeking to upend those narratives and perceptions. Over the past year, we have covered several such stories, whether it is the Lummi Nation developing a traveling exhibit that highlights Native American environmental values, programs at the Smithsonian’s Museum of the American Indian to change school curricula around Thanksgiving, an exhibit at the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum that lifts up struggles in the nation’s capital around gentrification, the opening of the art world to more curators of color, or the launch of a museum in Montgomery, Alabama that scrutinizes the nation’s long history of lynching.

But just in case we needed a reminder that the dominant narratives remain, well, dominant—Somáh Haaland in Teen Vogue tells a story about her recent visit to the Jamestown Settlement, a so-called “living history” museum located near the site of the first permanent English colony in what would become the United States.

Haaland was in southeastern Virginia, she explains, because she was accompanying her mother, Deb Haaland, who had just become one of the first two Native American women in US history to be elected to Congress. “All of the freshman members of Congress, along with their families, were invited to Williamsburg, Virginia, for a New Member Seminar,” she said. “While members attended workshops, family members were given options for activities, including historical tours.” Haaland visited nearby Jamestown.

The Jamestown Settlement and the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown is managed by the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, “an educational agency of the Commonwealth of Virginia.” You can get a flavor for their take on history from the museum’s website. As its home page explains, “In 2019, Jamestown Settlement will be a stage for engaging events and programs as part of the 2019 Commemoration, American Evolution, marking the 400th anniversary of key historical events that occurred in Virginia in 1619 that continue to influence America today.” Somehow, the word slavery is omitted, replaced by the phrase, “the arrival of the first recorded Africans to English North America”—as if the Africans came to America by choice.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Describing her visit, Haaland notes that she “saw several signs with information that claimed, ‘Africans were brought to Virginia…this process helped shape African American culture,’ and, ‘The founding of Jamestown sparked…cultural encounters that helped shape our nation and the world,’” ignoring the violence behind said “encounters.”

Haaland adds:

I stood at the back of my group and fought the urge to correct our guide, demanding that they speak the truth about atrocities committed against Natives and Africans. I was suddenly brought to tears, both by the thought of pre-colonization and by the concept that this is how Indian people are still showcased: as primal, exotic attractions. These people, my people, continue to be talked about like far-off legends who lived in the past and no longer exist.

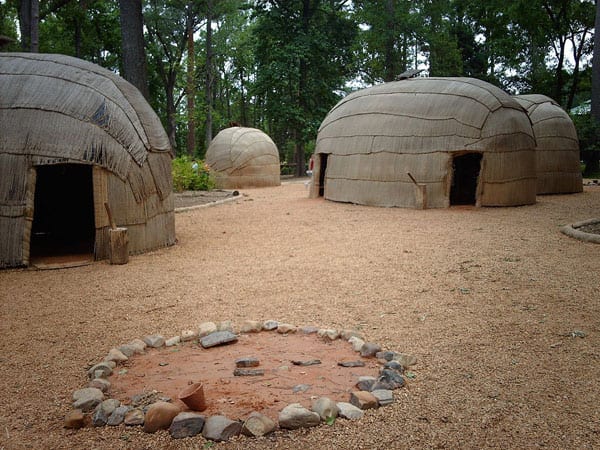

The museum also includes an outdoor “Indian Village” where, Haaland explains, “multiple employees, several of whom appeared to be white, dressed as Indians in buckskin robes, rattlesnake tails, and red face paint.” Haaland adds that, “There are many reasons why this type of display isn’t okay. First, it promotes the idea that Native people are extinct…. Similar to blackface, these types of exhibits make a mockery of Indigenous identities. The reason we wore our traditional clothes to the swearing-in was to honor our ancestors. It’s not okay to dress up, using another culture as a costume. It’s not okay on Halloween. It’s not okay at Coachella. It’s not okay in a history museum.” Haaland emphasizes that these (mis)representations matter “because so much of America still sees us as savages in glass cases and our traditional dress as costumes to be worn.”

Haaland concludes, however, on a hopeful note: “My mother, standing on the floor of the US Congress in moccasins and turquoise jewelry, is a tangible symbol that we have survived. It’s past time for us to take ownership of our history, and the beginning of the 116th Congress is the perfect place to start.”—Steve Dubb