Editor’s Note: The Nonprofit Quarterly and the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) are pleased to present the second in a series of articles based on insights and lessons from Philamplify, NCRP’s new initiative that combines expert assessments with stakeholder feedback to help improve the effectiveness and impact of the country’s foundations.

When I was in college, I was intimidated by speaking with professors during their office hours. It wasn’t their personalities that scared me; rather, it was their positions of authority. The thought of having to interact with them one on one and the pressure to sound like I knew what I was talking about was terrifying. Then in graduate school, when I was invited to address my professors by their first name, I came to see them more as thought partners than judges of my intellectual worth. Thinking back, part of what allowed that shift in attitude to happen was feeling less pressure to produce great grades and more freedom to focus on learning.

Similarly, when I first started writing grant proposals, I was daunted by my interactions with grantmakers. It felt like there was a lot at stake, and I was afraid of making a bad impression. When I became a consultant and started working with foundation clients, I was able to see them as peers. I realized that they, like me, still had things to learn and I was helping them do that by gathering data and analyzing the impact of their grantmaking. Grantees were frequently an important resource in that information gathering process.

To what extent is shared learning at the heart of foundation-nonprofit relationships? I would say, based on what we’re hearing through our Philamplify assessments to date, that it should be.

In this month’s post, I take a look at one of the recurring themes among the results of the first set of assessments: how nonprofits rate and describe the effectiveness of foundation-nonprofit partnerships.

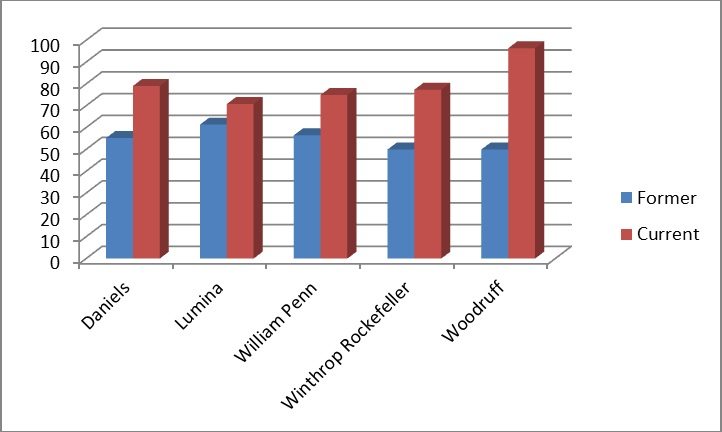

In reviewing the data from our grantee surveys for our Philamplify assessments of the Daniels Fund, Lumina Foundation for Education, Robert W. Woodruff Foundation and William Penn Foundation, as well as our pilot assessment of the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, we observed that a majority of surveyed leaders rated the nonprofit-foundation partnership as “very effective.” We also noted that current grantees view foundation partnerships more favorably than former grantees.

Percent of Grantee Survey Respondents who Rated Foundation Partnership “Very Effective”

Perhaps this is not surprising. Current grantees may be appreciative of the funds and therefore more inclined to feel positively toward the foundation; former grantees may be disappointed that they are no longer receiving funds and therefore feel less positively. I would argue that both perspectives are useful. Having taken off their rose-colored glasses, former grantees may be able to offer a more clear-eyed view of the foundation. Current grantees experience how the foundation behaves today, which may be different than how it behaved a year, two years, or even three years ago.

Whether nonprofit leaders view a foundation as a very effective partner or not, they tend to agree on the most important attributes of that relationship. Four characteristics are most frequently cited as key to effective donor-grantee partnerships:

- Relationship with foundation staff, rooted in dialogue and trust

- Clear, consistent foundation communication with grantees

- Foundation understanding of the mission of the nonprofit and willingness to fund its objectives and needs

- Application processes that support mutual goals and help the applicant organization develop and refine its plans

This finding echoes the extensive survey data that the Center for Effective Philanthropy has collected from Grantee Perception Reports. These found that key predictors of strong relationships are: understanding of grantee’s goals and strategies, helpfulness of selection process and mitigation of pressure to modify priorities, expertise/understanding of the field and community, and initiation and frequency of contact. CEP offers concrete advice to foundation staff in each of these areas.

The amount and flexibility of grant funding were also frequently cited, but not as much as these other characteristics. This raises questions: Why do many grantees want more than just a check from foundations? And why is this good news for grantmakers?

Many grantees realize that foundation staff can offer resources beyond the check. For example, three of the five sets of survey data showed that grantees placed a high value on the knowledge and expertise of foundation staff and their role as thought partners. Four of the five foundations whose grantees we surveyed have a strong local or regional focus to their grantmaking, and their grantees appreciated when foundation staff took the time to show their support by coming to grantee events and publicizing their work.

But thought partnership goes two ways, and many grantees value the opportunity to bring their own ideas to foundation staff and show them firsthand the kinds of issues they are addressing as well as the positive impact on the ground. A grantee suggestion from one survey hints at this dual purpose:

“Continue to encourage individual grant officers to create a meaningful relationship with the grantees; this is constructive feedback and helps in shaping the program both to achieve the goals of the foundation [and] achieve greater success in our organization.”

Grantees know they have a lot of experience and knowledge that can inform foundation strategy. They want structured occasions to provide such input. As another survey respondent suggested, “I would develop an advisory group of grantees to provide feedback on future direction. This group could help the foundation [with] understanding the issues and changing needs of the organizations it supports.” That’s why three of our most recent assessments—Lumina Foundation, Daniels Fund, and the California Endowment—specifically recommended that the foundation seek grantee input when developing and refining goals and strategies.

And that’s the good news for grantmakers: Strong relationships with grantees are essential components of effective foundation strategies, offering learning opportunities that can lead to better outcomes and transformative impact on communities and issues we care about.

The Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation (WRF) and William Penn Foundation both held local focus groups and meetings with grantees and other stakeholders when they each undertook strategic planning processes a number of years ago. WRF held a meeting with grantees to get input on strategy adjustments for its “Moving the Needle” agenda, sharing its NCRP assessment to inform discussions.

It is necessary but not sufficient for foundation staff to have a strong relationship with nonprofit leaders. Our Philamplify research found that when there is a disconnect between program officers and top decision-makers within a foundation, or when a major change in foundation strategy—sometimes resulting in staff turnover—is poorly communicated, the relationship and bond of trust with grantees often falters. Grantmakers need to ensure internal alignment of goals and healthy internal communication as they seek mission alignment and strong two-way communication with external partners.

Developing and implementing a grantmaking strategy to effectively achieve certain goals is, by its nature, both relational and iterative. It involves getting to know your intended beneficiaries’ community, understanding how the issues you are trying to address affect them, and getting real-time data about what’s happening on the ground to make mid-course adjustments. Your grantees are the perfect resource for this type of learning. But to get reliable information, you need your grantees’ trust—the kind that is built over time through strong two-way communication, honest dialogue, alignment of mission, and shared strategy development.

Lisa Ranghelli is director of foundation assessment at NCRP. She also served as the primary researcher for the Philamplify assessment of the William Penn Foundation. Follow @ncrp and #Philamplify conversations on Twitter.

v:* { behavior:url(#default#VML); } o:* { behavior:url(#default#VML); } w:* { behavior:url(#default#VML); } .shape { behavior:url(#default#VML); }

What “effective nonprofit-foundation partnership” means and why it’s good for foundations.

Beyond the Check

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

By Lisa Ranghelli

Editor’s Note: The Nonprofit Quarterly and the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) are pleased to present the second in a series of articles based on insights and lessons from Philamplify, NCRP’s new initiative that combines expert assessments with stakeholder feedback to help improve the effectiveness and impact of the country’s foundations.

When I was in college, I was intimated by speaking with professors during their office hours. It wasn’t their personalities that scared me; rather, it was their positions of authority. The thought of having to interact with them one on one and the pressure to sound like I knew what I was talking about was terrifying. Then in graduate school, when I was invited to address my professors by their first name, I came to see them more as thought partners than judges of my intellectual worth. Thinking back, part of what allowed that shift in attitude to happen was feeling less pressure to produce great grades and more freedom to focus on learning.

Similarly, when I first started writing grant proposals, I was daunted by my interactions with grantmakers. It felt like there was a lot at stake, and I was afraid of making a bad impression. When I became a consultant and started working with foundation clients, I was able to see them as peers. I realized that they, like me, still had things to learn and I was helping them do that by gathering data and analyzing the impact of their grantmaking. Grantees were frequently an important resource in that information gathering process.

To what extent is shared learning at the heart of foundation-nonprofit relationships? I would say, based on what we’re hearing through our Philamplify assessments to date, that it should be.

In this month’s post, I take a look at one of the recurring themes among the results of the first set of assessments: how nonprofits rate and describe the effectiveness of foundation-nonprofit partnerships.

In reviewing the data from our grantee surveys for our Philamplify assessments of the Daniels Fund, Lumina Foundation for Education, Robert W. Woodruff Foundation and William Penn Foundation, as well as our pilot assessment of the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, we observed that a majority of surveyed leaders rated the nonprofit-foundation partnership as “very effective.” We also noted that current grantees view foundation partnerships more favorably than former grantees.

Percent of Grantee Survey Respondents who Rated Foundation Partnership “Very Effective”

Perhaps this is not surprising. Current grantees may be appreciative of the funds and therefore more inclined to feel positively toward the foundation; former grantees may be disappointed that they are no longer receiving funds and therefore feel less positively. I would argue that both perspectives are useful. Having taken off their rose-colored glasses, former grantees may be able to offer a more clear-eyed view of the foundation. Current grantees experience how the foundation behaves today, which may be different than how it behaved a year, two years, or even three years ago.

Whether nonprofit leaders view a foundation as a very effective partner or not, they tend to agree on the most important attributes of that relationship. Four characteristics are most frequently cited as key to effective donor-grantee partnerships:

1. Relationship with foundation staff, rooted in dialogue and trust

2. Clear, consistent foundation communication with grantees

3. Foundation understanding of the mission of the nonprofit and willingness to fund its objectives and needs

4. Application processes that support mutual goals and help the applicant organization develop and refine its plans

This finding echoes the extensive survey data that the Center for Effective Philanthropy has collected from Grantee Perception Reports. These found that key predictors of strong relationships are: understanding of grantee’s goals and strategies, helpfulness of selection process and mitigation of pressure to modify priorities, expertise/understanding of the field and community, and initiation and frequency of contact. CEP offers concrete advice [LR1] to foundation staff in each of these areas.

The amount and flexibility of grant funding were also frequently cited, but not as much as these other characteristics. This raises questions: Why do many grantees want more than just a check from foundations? And why is this good news for grantmakers?

Many grantees realize that foundation staff can offer resources beyond the check. For example, three of the five sets of survey data showed that grantees placed a high value on the knowledge and expertise of foundation staff and their role as thought partners. Four of the five foundations whose grantees we surveyed have a strong local or regional focus to their grantmaking, and their grantees appreciated when foundation staff took the time to show their support by coming to grantee events and publicizing their work.

But thought partnership goes two ways, and many grantees value the opportunity to bring their own ideas to foundation staff and show them firsthand the kinds of issues they are addressing as well as the positive impact on the ground. A grantee suggestion from one survey [y2] hints[LR3] [y4] at this dual purpose:

“Continue to encourage individual grant officers to create a meaningful relationship with the grantees; this is constructive feedback and helps in shaping the program both to achieve the goals of the foundation [and] achieve greater success in our organization.”

Grantees know they have a lot of experience and knowledge that can inform foundation strategy. They want structured occasions to provide such input. As another survey respondent suggested, “I would develop an advisory group of grantees to provide feedback on future direction. This group could help the foundation [with] understanding the issues and changing needs of the organizations it supports.” That’s why three of our most recent assessments—Lumina Foundation, Daniels Fund, and the California Endowment—specifically recommended that the foundation seek grantee input when developing and refining goals and strategies.

And that’s the good news for grantmakers: Strong relationships with grantees are essential components of effective foundation strategies, offering learning opportunities that can lead to better outcomes and transformative impact on communities and issues we care about.

The Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation (WRF) and William Penn Foundation both held local focus groups and meetings with grantees and other stakeholders when they each undertook strategic planning processes a number of years ago. WRF held a meeting with grantees to get input on strategy adjustments for its “Moving the Needle” agenda, sharing its NCRP assessment to inform discussions.

It is necessary but not sufficient for foundation staff to have a strong relationship with nonprofit leaders. Our Philamplify research found that when there is a disconnect between program officers and top decision-makers within a foundation, or when a major change in foundation strategy—sometimes resulting in staff turnover—is poorly communicated, the relationship and bond of trust with grantees often falters. Grantmakers need to ensure internal alignment of goals and healthy internal communication as they seek mission alignment and strong two-way communication with external partners.

Developing and implementing a grantmaking strategy to effectively achieve certain goals is, by its nature, both relational and iterative. It involves getting to know your intended beneficiaries’ community, understanding how the issues you are trying to address affect them, and getting real-time data about what’s happening on the ground to make mid-course adjustments. Your grantees are the perfect resource for this type of learning. But to get reliable information, you need your grantees’ trust—the kind that is built over time through strong two-way communication, honest dialogue, alignment of mission, and shared strategy development.

Follow @ncrp and #Philamplify conversations on Twitter.