July 10, 2017; Chicago Reporter

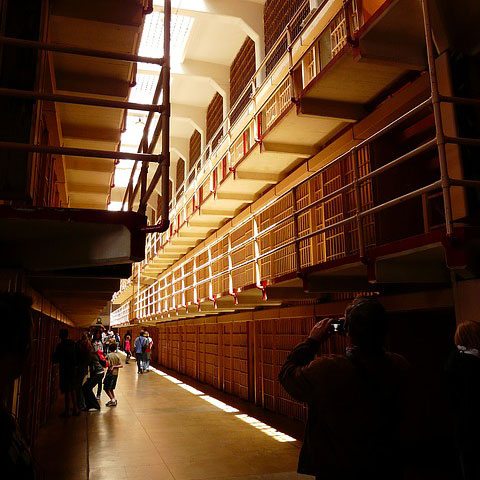

Hidden away in cinderblock cells across the country, disenfranchised voters wait to be given their turn to exercise their constitutionally mandated rights. Even when the law allows inmates to vote, they are often not given the opportunity to do so. A recent Illinois law allows people who are in jail awaiting trial but have not yet been convicted to vote in person, rather than by mail.

According to the Chicago Reporter, “On March 28, for the first time in nearly a decade, eligible inmates were allowed to vote in person and submit their ballots to election officials rather than mail them in,” a practice that increases voting rates. “Cook County Jail is among a few places in the nation that permits in-person voter registration and voting. The county clerk’s office and volunteers worked with jail officials to set up polling places—in the gym for women, in a chapel for men in maximum security.”

Is this an overlooked opportunity for nonprofit advocacy?

Voting laws for people accused or convicted of crimes vary from state to state. Maine and New Hampshire allow anyone, even incarcerated felons, to vote. Eleven states, including Nevada, Florida, and Louisiana, do not allow either incarcerated people awaiting trial or felons who’ve been released to vote. Most states are in the middle, and restrict only inmates and parolees.

The Chicago Reporter noted that “in the 2016 general election, nearly 1,200 ballots came from Cook County Jail, whose population hovers around 7,000 and is 74 percent black.” The rest of the state’s inmates were not so lucky; the paper also noted that “the law doesn’t require election authorities to report vote totals from the state’s jails. As a result, only 23 of 109 election authorities in Illinois reported the votes [from jails] from the 2016 general election, according to records from the Illinois Board of Election.”

According to The Sentencing Project, a reform advocacy group, one in 40 adult Americans loses the right to vote because they’ve broken the law. But the deeper story has to do with America’s racially biased justice system and the continued exclusion of people of color from equal rights and participation.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The racially biased criminal code and sentencing laws in the U.S. means that a higher proportion of people of color are behind bars or otherwise disenfranchised. Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow explains how the criminal code was written to target people of color. The Sentencing Project states that “Black males born in 2001 had a 33 percent chance of serving time in prison at some point in their lives; Hispanic males had a 17 percent chance; white males had a six percent chance. According to the American Civil Liberties Union, “sentences imposed on Black males in the federal system are nearly 20 percent longer than those imposed on white males convicted of similar crimes.”

This carries over into voting rights: The Sentencing Project reports that “2.2 million African Americans, or 7.7 percent of black adults, are disenfranchised, compared to 1.8 percent of the non-African American population.”

Though it’s hard to argue that disenfranchising voters “benefits” the country in any way, of the estimated 6.1 million missing votes, most would likely have been Democratic, giving Republican state legislatures little party-based incentive to change the laws or the practices that keep inmates from voting. Business Insider noted that “one study even suggested that allowing felons to vote in Florida could have tipped the 2000 presidential election to Democrat Al Gore.”

Most Republican-leaning states have stricter voting and sentencing laws. In fact, this year, Attorney General Jeff Sessions, originally an a Republican senator from Alabama with a strong anti-civil rights record, made it harder to give any leniency to those accused or convicted of crimes, despite bipartisan support for criminal justice reform.

So, what are nonprofits to do? Part of the problem is, even in states where they’re allowed to vote, inmates often don’t know their rights; it’s often up to prison or jail officials to enforce the right to vote or provide an opportunity for inmates to do so. The Chicago Reporter found that “in Will County, election officials have no process to go inside the local jail to register inmates and have never been asked to do so”—and that’s just one county. The Sentencing Project’s executive director Marc Mauer said that “in most cases it hasn’t occurred to [prison officials] that this is something that they should be considering in their local jails.”

This is one area where, in many cases, laws may not have to change; programs just need to be initiated. Volunteers in Cook County set up tables in the gym to register inmates and got 1,200 voters on the rolls. It may be more difficult in some places, but the cost of inaction is too high to leave this issue alone.—Erin Rubin