January 9, 2015; Al Jazeera

The new mayor of Newark, New Jersey, Ras Baraka, was elected as a political progressive, an ostensible advocate for the city’s poor after the administration of Cory Booker, who was seen as strongly oriented toward downtown development. As a progressive, Baraka now has to explain why he quadrupled the fee that the Newark Municipal Court charges low-income defendants for the assistance of a public defender.

Essentially, Baraka is adopting an increasingly popular means of funding public services—charging the users of public services higher and higher “user fees.” The new fee for criminal defendants is going to be $200, up from $50. Office of the Public Defender attorney Anthony Cowell pointed out that most of the clients he represents don’t have $200 to pay as a fee. “It’s been said it’s a revenue-generator, but you’re charging people who absolutely can’t afford it,” Cowell said. “They’re homeless, they’re mentally ill, they’re in shelters…”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This new policy, along with a host of new fees being charged in the New Jersey Superior Court system, puts Newark and the state of New Jersey into the company of Alabama, Mississippi, Missouri, and Texas, which Al Jazeera’s E. Tammy Kim writes have been using “‘cash register’ courts more focused on padding local budgets than carrying out judicial functions.” As Kim correctly noted, this was the situation in St. Louis County, Missouri, where 40 percent of local government revenues come from fines for traffic tickets and petty crime.

Baraka’s office emailed Al Jazeera that the fee wouldn’t be a problem because municipal court judges have the authority to reduce or even waive the fee. However, a municipal court staff person who declined to be identified said that “most judges do not bother making decisions about the application fee.” In practice, the municipal court user fee gets lost in the “bureaucratic shuffle,” but relying on bureaucratic incompetence as an out for people who would be otherwise be hit with the fee is haphazard and inadequate public policy making.

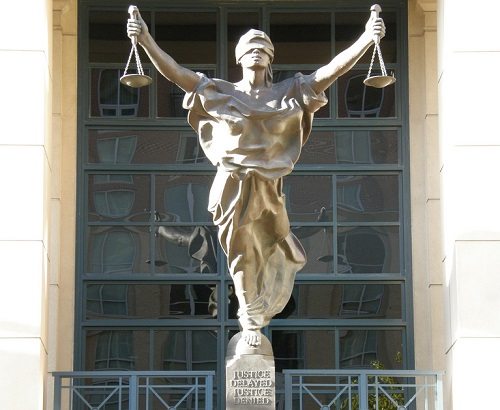

Put this into a broader context. The law of the land regarding legal representation emanates from the Gideon v. Wainwright decision of 1963, in which states were required, per the U.S. Constitution, to provide legal representation to criminal defendants who couldn’t afford to hire lawyers for themselves. States like New Jersey found ways of limiting where and when it would provide public defenders and charged the initially small user fee despite the nomenclature that public defenders were “free.” Charging criminal defendants $200 makes the notion of “free” public defenders for indigent defendants sadly laughable. In some states, defendants face not only user fees for attorneys, but payments for fines, court costs, and even probation services.

In 2012, Louisiana was charging $35 to indigent criminal defendants who were later convicted and was threatening to raise the fee levels. The Brennan Center for Justice concluded that the Louisiana fee structure “creates a system that undermines the Constitutional right to conflict-free counsel by forcing attorneys to rely on their clients’ convictions for much needed funding…[and] acts as an illogical tax on indigent defendants.”

Louisiana is hardly alone; the Brennan Center found that “of the 15 states with the largest prison populations, 13 allow low-income defendants to be charged fees for exercising their right to counsel.” But Newark, on its own, under the guidance of its new, progressive mayor, is moving the “Brick City” into the unwanted echelon of governments that through user fees are taxing the poorest of the poor.—Rick Cohen