This article is from the Nonprofit Quarterly’s fall 2017 edition, “The Changing Skyline of U.S. Giving.”

Responsible investment means incorporating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors into investment decisions to generate sustainable returns and better manage risk. On a human level, it means incorporating the desire to make a difference in the world into the investment process. Green bonds, fixed income instruments that fund projects with environmental and/or climate benefit, are a type of responsible investment.1 More broadly, they are an example of leadership from the investment community in addressing the threat of climate change. In the wake of recent catastrophic hurricanes, this article provides an overview of the green bond market for potential investors and issuers seeking to do more to protect the planet.

Market Size and Trajectory

Green bonds have grown rapidly since they were invented by investors in 2007 to fund projects with climate or environmental benefits. Since then, two categories of green bonds (labeled and unlabeled) with four main structures (use of proceeds, revenue, project, and securitized) have emerged from a broadening range of issuers. Global green bond issuance is projected to double in 2017 from $93.4 billion of issuance in 2016,2 after doubling from $42 billion in 2015.3 With the Paris Climate Agreement and China’s clean energy campaign as drivers of continuing growth, this deep dive into the emerging asset class is warranted. By way of background: under the Paris Climate Agreement, investors with an aggregate $11 trillion of assets under management (AUM) committed to build a green bond market,4 and the United States committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions 26 to 28 percent below the 2005 level by 2025.5

Despite U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, over a thousand U.S. mayors, governors, college and university leaders, businesses, and investors pledged to continue to work toward the United States’ nationally determined contribution to mitigate global warming.6 Among states, California, Washington, and New York are leaders in taking aggressive action on climate change.7 Green bond issuance facilitates countries and states alike in funding their carbon-reduction targets. Last year, China accounted for approximately 40 percent of global green bond issuance,8 including China’s Bank of Communications’ record ¥30 billion ($4.3 billion) two-tranche green bond issuance in November 2016.9

Green Bond Sectors, Proceeds, Standards, and Structures

There are five sectors of green bonds: renewable energy development, energy efficiency improvements, climate-smart agriculture, transport improvements, and water resource management and climate-smart water infrastructure. The energy sector generates about 40 percent of global CO2 emissions. Agriculture, including associated deforestation, is the largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, and transport contributes 15 percent of greenhouse gas emissions.10 Green bond proceeds run the gamut from climate change mitigation to climate change adaptation. Climate change mitigation projects facilitate reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, among other things. Climate change adaptation projects reduce suffering caused by climate change and build resilience, including protection against flooding.11 Labeled green bonds are certified as green, while unlabeled green bonds simply have issuances linked to projects that produce environmental benefit.12 The Climate Bonds Initiative estimated $576 billion of unlabeled green bond issuance in 2016 across transport, energy, buildings and industry, water, waste and pollution control, and agriculture and forestry.13

Green Bond Principles, Climate Bonds Standard & Certification Scheme, and external reviews mitigate the risk that green bond proceeds are used for projects with limited environmental benefit.14 Although there is no universal approach to designating use of proceeds as “green,” issuers, investors, and rating agencies have established frameworks, and approximately 60 percent of green-labeled bonds are subject to external review. For example, Green Bond Principles are voluntary guidelines on use of proceeds, project evaluation and selection, management of proceeds, and reporting crafted in part by the International Capital Market Association.15 In addition, the Climate Bonds Standard & Certification Scheme, administered by the Climate Bonds Initiative, entails third-party verification pre- and post-issuance to ensure that the bond meets the requirements.16 Climate Bonds Initiative, an investor-focused nonprofit governed by a board that represents $34 trillion in AUM, maintains the Climate Bonds Standards. Lastly, mainstream ratings agencies S&P and Moody’s have developed methodologies to rate green bonds on their “greenness.”17

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

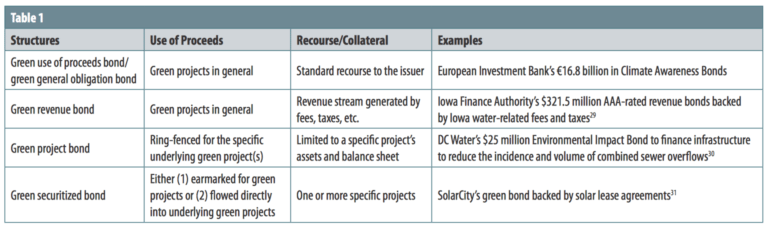

Most of the approximately $160 billion of green bonds outstanding globally are use of proceeds bonds.18 The four major green bond structures are set forth in Table 1.19

Structural innovations include environmental impact bonds (in which the performance risk of the green bond is shared among the issuer and the investors),20 and sharia-compliant green sukuks (which harness Islamic finance for climate-friendly investments).21 China-owned Edra Power Holdings Sdn Bhd’s unit, Tadau Energy Sdn Bhd, issued the world’s first green sukuk this past June.22

Issuer Types

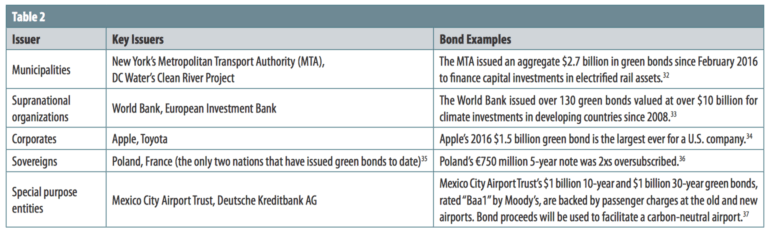

Green bonds were primarily issued by supranational issuers through 2012. Starting in 2013, issuer types broadened, with financial institutions and nonfinancial corporates driving 50 percent and 24 percent, respectively, of 2016 full-year green bond issuance.23 Last fall, British bank HSBC estimated that labeled green municipal bonds represented 8 percent of the total labeled green bond issuance since 2007.24 If Trump’s tax reform is successful, lower taxes would reduce the attractiveness of municipal bonds’ tax-exempt status.25 Special-purpose entities, such as partnerships and trusts, drove 5 percent of green bond issuance in 2016.26 In December 2016, Poland became the first sovereign nation to issue a green bond, followed by France’s record €7 billion sale of twenty-two-year green bonds in January 2017.27 (See Table 2.)

The Road Ahead

The Climate Bonds Initiative projects that $1 trillion in green bonds annually will be issued by 2020.28 This projection is set against the backdrop of an estimated $93-trillion cost to replace fossil fuel–powered infrastructure with low-carbon alternatives to achieve the Paris Agreement’s objective to limit global temperature rise to below 2°C.

This includes $8 trillion in the United States.38 As over one hundred leading businesses contemplate their support for the Michael Bloomberg–chaired Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), their consideration of the implications for a 2°C scenario should drive climate adaptation projects and bonds to finance them.39 While numerous Trump administration policies generate headwinds for the climate bonds market, this networked age allows many American actors connected below the level of the U.S. federal government to continue to build and finance climate-friendly infrastructure.40

This includes $8 trillion in the United States.38 As over one hundred leading businesses contemplate their support for the Michael Bloomberg–chaired Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), their consideration of the implications for a 2°C scenario should drive climate adaptation projects and bonds to finance them.39 While numerous Trump administration policies generate headwinds for the climate bonds market, this networked age allows many American actors connected below the level of the U.S. federal government to continue to build and finance climate-friendly infrastructure.40

Notes

- This article should not be construed as investment advice.

- Umesh Desai, “Moody’s says green bond issuance set for another record year,” Reuters, January 19, 2017.

- Bonds and Climate Change: The State of the Market in 2016 (London: Climate Bonds Initiative, July 2016), 6.

- John Geddie and Alister Doyle, “Climate changing for ‘green bonds’ even in face of Trump skepticism,” Reuters, January 12, 2017.

- Brookings Institution online; The Avenue; “Green bonds take root in the U.S. municipal bond market,” blog entry by Devashree Saha, October 25, 2016.

- “We are still in: Open letter to the international community and parties to the Paris Agreement from U.S. state, local, and business leaders,” wearestillin.com.

- New York State Governor’s Press Office, “New York Governor Cuomo, California Governor Brown, and Washington Governor Inslee Announce Formation of United States Climate Alliance,” press release, June 1, 2017.

- Lucy Hornby, “China leads world on green bonds but the benefits are hazy,” Financial Times, May 3, 2017.

- Geddie and Doyle, “Climate changing for ‘green bonds’ even in face of Trump skepticism.”

- World Bank, Green Bond: Impact Report (Washington, DC: World Bank, June 2016), 8.

- Ibid., 1, 6, 9.

- Financing Solutions for Sustainable Development: Green Bonds (New York: United Nations Development Programme, 2016).

- Bonds and Climate Change, 3.

- Financing Solutions for Sustainable Development: Green Bonds.

- The Green Bond Principles, 2016: Voluntary Process Guidelines for Issuing Green Bonds (London: International Capital Market Association, June 16, 2016).

- Climate Bonds Standard & Certification Scheme (London: Climate Bonds Initiative, February 2017).

- Green Bonds: Green is the new black (Toronto: RBC Capital Markets, April 4, 2017), 11.

- Ibid., 8.

- “Explaining green bonds,” Climate Bonds Initiative website, accessed September 12, 2017; Financing Solutions for Sustainable Development: Green Bonds; and Justin Kuepper, “What Are Green Muni Bonds?,” MunicipalBonds.com, March 10, 2016.

- DC Water, “DC Water, Goldman Sachs and Calvert Foundation pioneer environmental impact bond,” press release, September 29, 2016.

- “Malaysia’s 1st green sukuk under SC’s SRI sukuk framework,” Malaysian Reserve, July 28, 2017.

- Eva Yeong, “Edra Power’s Tadau Energy issues Malaysia’s first ‘green’ sukuk,” theSundaily, July 27, 2017. (“Sdn Bhd” is the short form for “Sendirian Berhad,” a Malaysian business term meaning “private limited,” similar to the abbreviation “Ltd.”)

- Green Bonds: Green is the new black, 3.

- S&P Global; Our Insights; “What’s Next for U.S. Municipal Green Bonds?,” blog entry by Kurt Forsgren, September 7, 2016.

- Romy Varghese and Sahil Kapur, “U.S. Tax Cuts Could Drive Key Buyers Away from Muni-Bond Market,” Bloomberg, April 7, 2017.

- Green Bonds: Green is the new black, p. 4.

- “France issues first ‘green bonds’ with record 7 bln euro sale,” Energy & Green Tech, Phys.org, January 25, 2017.

- Climate Bonds Initiative; Climate Bonds Blog; “Green Bond Policy Highlights from Q1–Q2 2017,” by Andrew Whiley, July 18, 2017.

- Green City Bonds Coalition, How to Issue a Green Muni Bond: The Green Muni Bonds Playbook (London: Climate Bonds Initiative, 2015), 3.

- DC Water, “DC Water, Goldman Sachs and Calvert Foundation pioneer environmental impact bond.”

- SolarCity, “SolarCity Launches First Public Offering of Solar Bonds,” press release, October 15, 2014.

- “Metropolitan Transport Authority,” Climate Bonds Initiative website, Standard, accessed September 6, 2017.

- World Bank, “World Bank Green Bonds Reach $10 billion in Funding Raised for Climate Finance,” press release, April 7, 2017.

- Daniel Eran Dilger, “Apple’s Green Bonds funded $441.5 million of environmental safety, conservation climate change action in 2016,” AppleInsider, March 8, 2017.

- “France issues first ‘green bonds’ with record 7 bln euro sale.”

- Andrzej Sutkowski, Cenzi Gargaro, and Tallat Hussain, “Sovereign Green Bonds: Poland sets a precedent,” Publications & Events, White & Case website, January 17, 2017.

- Moody’s Investors Service, “Moody’s assigns Green Bond Assessment (GBA) of GB1 to Mexico City Airport Trust Senior Secured Notes,” press release, September 6, 2016; and Anthony Harrup, “Mexico Sells $2 billion in Green Bonds to Help Finance Airport,” Wall Street Journal, September 23, 2016.

- Yale Center for Business and the Environment; Clean Energy Finance Forum; “California Treasurer Advances Green Bonds,” blog entry by Mark A. Perelman, August 1, 2017.

- “Statement of Support and Supporting Companies,” Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures website, June 2017.

- Anne-Marie Slaughter, The Chessboard and the Web: Strategies of Connection in a Networked World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017).