June 14, 2017; New York Times

NGOs operating in the Mediterranean Sea are venturing closer and closer to the Libyan shore in hopes of reaching refugees before they drown. Unfortunately, both migrants and smugglers have taken advantage of this impulse, worsening the overall situation for those at sea.

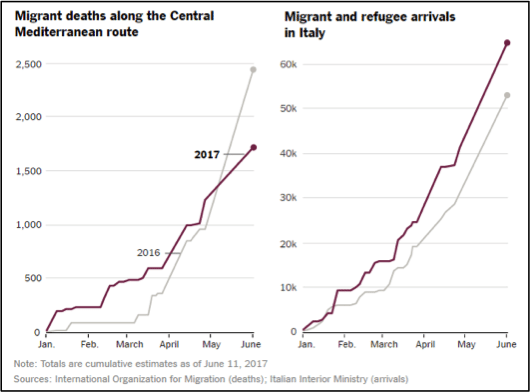

The migrant crisis in the Mediterranean, like the civil war in Syria, often drops out of the western world’s public consciousness when it doesn’t affect everyday life. Nevertheless, hundreds of thousands of people continue to flee war, famine, and persecution in African countries. In 2016, a record number of 181,459 people tried to cross into Europe from northern Africa. Eighty-nine percent of these traveled through Libya, and over 5,000 of them drowned.

Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, reports:

During 2015, and the first months of 2016, smuggling groups instructed migrants to make satellite phone calls to the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) in Rome to initiate targeted rescues on the high seas…Since June 2016, a significant number of boats were intercepted or rescued by NGO vessels without any prior distress call and without official information as to the rescue location. NGO presence and activities close to, and occasionally within, the 12-mile Libyan territorial waters nearly doubled compared with the previous year.

Both smugglers and migrants are aware that NGO presence on the sea is increasing and have taken advantage of the situation by sending more people in flimsier boats out to sea. According to the New York Times, “Smugglers use flimsy boats and provide just enough fuel to reach the edge of Libyan waters. Drivers can remove the engine and head back to Libya on another boat, leaving the migrants adrift until help arrives.”

Migrant death rates have continued to increase, despite increased rescue efforts, because of increased motivation to just get out on the water and the increasing unfitness of smugglers’ boats for the number of people on board. Stefano Argenziano, operation coordinator on migration for Doctors Without Borders, said, “The onset of anti-smuggling operations has accelerated the pace of the degradation.” A spokeswoman for Frontex, Izabella Cooper, pointed out that many people coming from non-coastal areas do not know how to swim.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Italy, where most of the refugees from North Africa end up, has a complicated relationship with its former colony. Libya has known less than a century of self-rule in its entire history. It has been ruled by the Spanish, Ottomans, and other governments from the time the Romans conquered it in 74 B.C. until the United Nations oversaw a transition to independence in 1951. As the last colonial rulers, the Italians built roads and trains but not a national identity that would permit Libya’s various territorial groups to work together. In fact, like most colonial powers, they deliberately encouraged internal divisions, which has led to dire conditions from which Libyans attempt to flee.

Italy and Libya have worked on this problem before. In 2008, in exchange for a promise of $5 billion over 25 years from Italy to address Libya’s economic conditions, Libya closed its coast to migrants. It worked, in a way; the migrant flow stopped. However, since Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi was overthrown in 2011, Libya has struggled to support a stable unified government that can build international partnerships and manage large humanitarian crises. As Doctors Without Borders pointed out, “Libya is not a party to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees” and there was widespread abuse of would-be immigrants.

Italy and Libya have entered into a new partnership, whereby the Italians train the Libyan coastguard to rescue the migrants and bring them back to Libya. However, since the government is still in formative stages, the deal has already run into legal issues. Opponents are concerned about the plan to put migrants in camps, exposing them to risk of abuse. In addition,

[Lawyers] disputed the ability of [Prime Minister Fayez al] Serraj to make such a deal on behalf of the Government of National Accord (GNA). This is because according to the Libyan Political Agreement, until it is approved by the House of Representatives, the GNA along with the State Council, has no legal standing.

While Libya and Italy work out their legal responsibilities and local NGOs search ever widening areas of the Mediterranean, hundreds of thousands of people are in transition, hoping to end up in a better life. Even if the migrants make it to Italy, there is no guarantee that they’ll be resettled in in the West. The U.S. accepts a paltry number of migrants, and other European countries, like Hungary, are closing their borders. As Rick Cohen noted in NPQ in 2015, the moral outrage that the West showed over Darfur and Somalia is notably absent for the migrant crisis; might it have something to do with people coming in, rather than aid going out? In Rick’s poignant words, “In anesthetizing public opinion, many world leaders have made us all crewmembers guiding the ‘damned’ to oblivion.”—Erin Rubin