May 2, 2017; Associated Press, “AP News”

The state of Georgia is exhibiting some isolationist tendencies when it comes to addiction treatment. Frustrated with the high number of Tennessee residents who cross into Georgia to receive methadone treatment, legislators introduced rules that make it harder to open more clinics in the areas of the state near the Tennessee border.

Georgia has 71 treatment centers, the most in the South; Florida has twice Georgia’s population, yet has only 69 centers. At least 12 states have fewer than 10 clinics each.

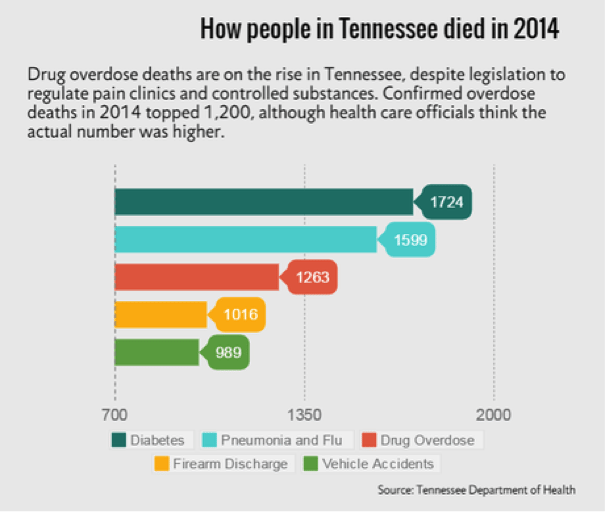

Tennessee has some of the worst health statistics in the country, particularly when it comes to addiction. Over 15 percent of the state’s adult residents lack basic medical care because of cost barriers; 16 percent have no health insurance. Over 1,200 residents died of substance abuse in 2014, and one in six Tennesseans are estimated to be in various stages of misuse, abuse, and treatment.

Tennessee has been struggling to deal with the problem since 2012, when the state passed the Prescription Safety Act and determined that mothers whose babies tested positive for drugs would go to jail (a provision of the law since ended). Strict rules were set governing pain management clinics and the dispensing of addiction treatment drugs like methadone (which state Medicaid doesn’t cover anyway), causing half the 300 addiction treatment centers in the state to close between 2015-2017.

Right across the border in Georgia, the opioid addiction crisis also looms, but treatment is a bit easier to find; according to the Associated Press, until the recent legislative efforts, “open competition was really the only constraint on the number of clinics in Georgia.” There are 71 treatment centers in Georgia, more than anywhere else in the South.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

AP reports that “Last year, one in five people treated at an opioid treatment center in Georgia came from out of state, according to state Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities records obtained by the Associated Press under an open records request. In the northwest corner of Georgia [near the Tennessee border], two out of every three patients were from out of state.”

It’s not that Georgia has a robust public health system; 22 percent of adults in the state have no insurance. Neither Georgia nor Tennessee joined the Medicaid expansion offered under the Affordable Care Act. But even though their overall healthcare system isn’t necessarily better than Tennessee’s, looser regulation encourages people to come to Georgia’s clinics. Georgia spends 14.4 percent of its state budget on addiction and substance abuse, and two percent of that amount on prevention and treatment.

Both states are alarmed by elements of the proposed American Health Care Act. One version of that bill eliminated the option offered by ACA for people to enroll in Medicaid specifically for substance abuse treatment, even if their state did not accept the federal expansion. Sixty-four percent of addiction treatment centers in the U.S. accept Medicaid, though most of these are concentrated in New England, California, Chicago, and Detroit.

Georgians are concerned about cost and safety when out-of-area patients come to treatment centers, officials say. Catoosa County Sheriff Gary Sisk said, “We can’t be the solution for all the surrounding states,” and expressed concerns about potential crime increases. (Fortunately for Sheriff Sisk, a 2016 report in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs found more crime associated with convenience stores than with opioid treatment programs.)

NPQ has written about the opioid epidemic affecting the entire U.S. and the insufficient congressional efforts to address it. U.S. Health & Human Services Secretary Tom Price recently promised an additional half billion dollars in state grants for prevention and treatment programs. However, that money may not help afflicted Tennesseans—or Georgians, or Texans, or anyone else—if regulations and limited Medicaid access strangle the ability of treatment centers to help their patients. NPQ has also written about the lack of philanthropy in the Deep South, where it seems like some serious advocacy and education on this issue is needed.

Georgia’s plan for limiting treatment tourism is legislation similar to Tennessee’s, which requires programs to demonstrate a need for their services in the area where they plan to open. (Given the statistics, this seems like it shouldn’t limit clinics at the moment, but it’s been effective in Tennessee.) If the legislation passes and is effective, nonprofits in the area may need to step up funding and efforts to deal with the patients left behind.— Erin Rubin