I read the story a final time and sent it to Myron, copying William Marchand, the attorney who reviewed all FairWarning stories pro bono. We didn’t put anything up on the website that was not legally bulletproof. FairWarning was a five-person operation if you counted the reporter in Washington, DC, who worked out of her home. One “wrong story” spawning a winning lawsuit or forced settlement would put us out of business, and then I’d be what I had been at least twice before in my career: a reporter with no place to go.

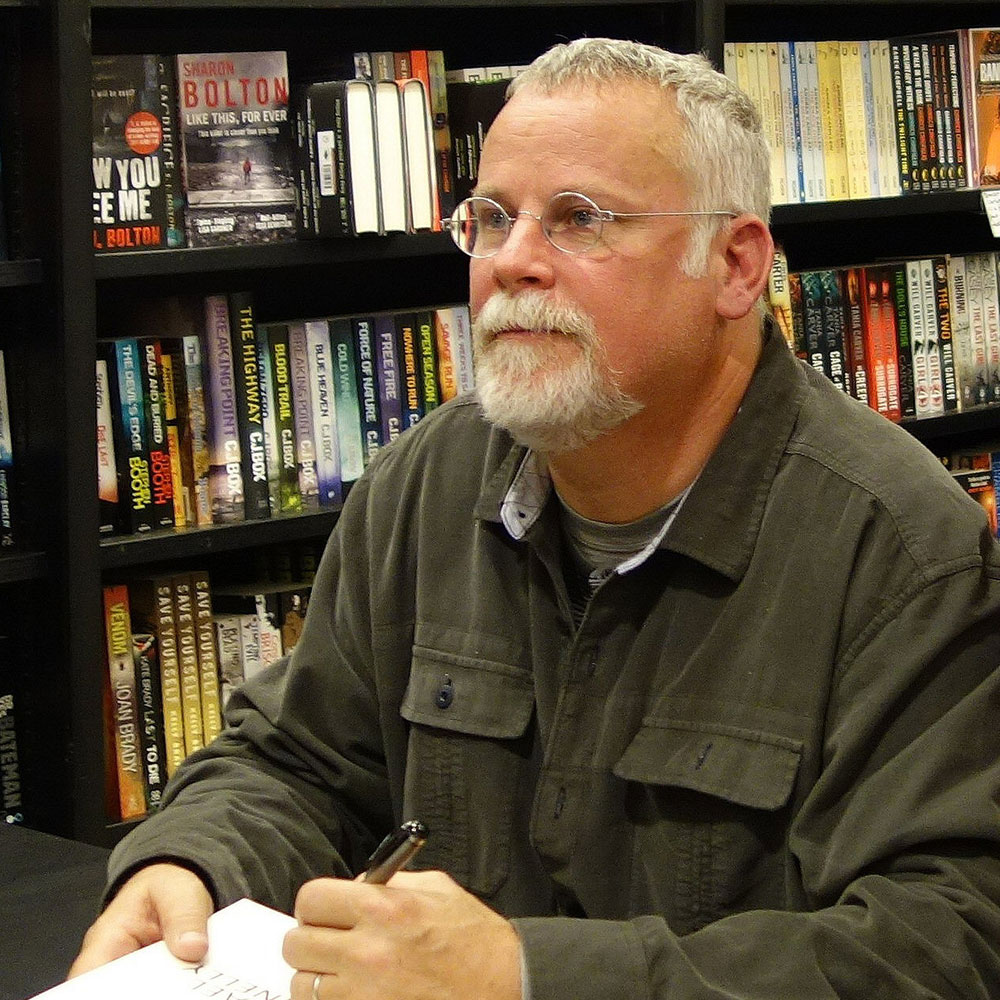

—Excerpted from Fair Warning by Michael Connelly

I have always immersed myself almost obsessively in fiction, and I have almost always worked in and written about nonprofits, so I know what I’m talking about when I say that writers consistently do such a piss-poor job of portraying nonprofits in fiction that it becomes notable when they don’t. Michael Connelly (MC), best-selling writer of mysteries including The Lincoln Lawyer and the Bosch series, is that exception, creating a nonprofit setting that is recognizable and attractive even for this relatively gruesome story.

The book is Fair Warning, and it is set in and around a nonprofit news operation with a similar name. The editor of that news site in the book—and, as it turns out, in real life—is Myron Levin (ML), a dogged truth-seeker and fundraiser who divides his time between ensuring that the tiny operation produces world-class stories that will make a difference to consumers and raising the money—day by day—that will sustain it. The fact that I do not need to make a distinction between the real-life guy and the character in the story is good news, because it means that Connelly got the underlying dynamics and culture of this nonprofit type right.

Levin is not the lead character, however; that central role belongs to Jack McEvoy, who appears periodically in Connelly’s writing as a central antihero character. In this book, McEvoy is a refugee from for-profit reporting, as is Levin. Both are dedicated to the news and willing to sacrifice for it.

Before I say more about the book, I want to emphasize why I believe that this mystery novel ought to be part of an important turning point in current literature. There is, in our society, a generalized illiteracy about nonprofits—the way they function, their ethical constructs, and their purposes. This creates a sense that they are not of “the real world” even though they are in greater and greater use as a counterbalance to the excesses of extractive capitalism. And, let’s be clear, it is extractive capitalism that has led hedge funds to buy and pillage many of this nation’s news operations, then leave them for dead or substantive irrelevance. Connelly knows this, as he told me in a recent interview:

MC: The nonprofit news field provides venues where people can go to practice journalism for its intrinsic value. There’s different purposes I use the McEvoy character for, but one of them is to reflect on where we are in the newspaper business. The last McEvoy book, I think, was 11 years ago, and he was at Daily Times, and they were laying off people, and it was all about that.

I think the next evolution is, well, what happened, or where did those people go and where did the story that they would write go? And, so, I just felt like it would be good to set the story at one of these nonprofits that have developed out of the collapse of the newspaper business and feature the struggles that the nonprofits face. I support a bunch of these sites and many of them are run by people that I was in the business with when I was a newspaper reporter.

So, it comes as no surprise that Connelly got Levin’s character right; not only does he sit on the board of FairWarning, but he’s known Levin since the Eighties, when they were both reporters at the L.A. Times. In some ways, he still sees himself as a journalist even as he is writing fiction.

MC: I write fiction, but there’s a lot of realism in it, and I go about the process like a journalist. You know, I want to be accurate. If I’m writing about L.A., I want to get the politics, the procedure, the locations, I want to get all that right and one of the ways I do it is I go out like a reporter, you know, with a notebook in my back pocket and my cell phone camera. And so I do a lot of the preparation to write fiction the way a newspaper reporter would do it to write a news story. You know, I take cops out to breakfast and ask them questions.

Actually, in this book in particular, Fair Warning, there’s an author’s note in the back about how what is in this book about DNA, as far as DNA research and as far as government protocols and regulations about DNA. That’s all accurate. It was accurate as of the time I wrote the book and as far as I know it’s still accurate. You know, there aren’t any regulations, and that’s what the “fair warning” in the book is.

Still, Levin was surprised when Connelly proposed the book concept:

ML: In August of 2019, I got an email from Mike saying, essentially, this might sound weird, but for my next book, which is another book in this Jack McEvoy series, I want to put McEvoy in your newsroom as an employee there. If you don’t want me to, that’s fine, and if the board needs to approve it, that’s fine, also—and, by the way, here are the first 50 pages of the first draft.

The board, as it turned out, thought the whole thing was a fine idea. The project surged forward, and when Levin received a complete first draft to look at, it felt largely on target. Even those things that were slightly off, he told me, were more in the realm of literary license than descriptive accuracy. Then, he mentioned the one thing in the book that struck me, as a fellow editor in such a venue, as hard to believe: a passage in the beginning where McEvoy says Levin told him to “stay in his lane”—he wouldn’t touch McEvoy’s ledes, but McEvoy should leave the headlines to him.

“People who know me might really laugh at that,” Levin said, “because, well, when a reporter turns in a story that has a headline, I usually don’t like them. But I’m glad to see it, because if it’s good, it saves me the trouble of thinking one up, and because I’m sort of in charge—I can reject it if I want. I don’t have to ask permission to write my own. But I just feel that I’m fairly ruthless about changing people’s ledes. Sometimes it really needs to happen, and I don’t really apologize for it.”

Levin left that alone as a fictional flourish, and he was probably right, but I do think this difference was notable to both of us because so much of what we must do in news right now is ensure we are not relying on unproductive frames of thought that take us down well-travelled dead ends, and those often are embedded in the ledes and conclusions of articles. On the other hand, he did ask for changes on the book’s description of the fictional outlet’s funding.

ML: In his draft, it talked about FairWarning raising money from consumer groups, but we don’t take any money from consumer groups because we do not want to encourage the perception that we let them reward us for coverage that might appear to be sympathetic to the work they do. Likewise, there were passages in the book about raising corporate money, but I said to Mike, we’ve never taken a nickel from a corporation; we’ve never been offered a nickel from a corporation. I wouldn’t say never do whatever under any circumstances, but it’s certainly not a place we raise money.

Connelly took the redirection easily because he saw the fundraising theme in his mystery as a piece of the drama:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

MC: As a board member I’ve been involved in raising funds for FairWarning, so I know the lifeblood of a nonprofit is declined supporters, and I know that’s hard to do. I thought there could be some drama in that if I introduced that into the story.

I’m an entertainer, I write thrillers, so obviously I’m thinking thriller, thriller, thriller, I have to write a thriller here, but at the same time that’s the trunk of the tree, and then the tree has many branches, and I knew a look into this world might be interesting.

What is so arresting about these small points is that they exhibit the lived differences in the ethical construct of the modern nonprofit news operation. Not only are those thought-provoking; for the uninitiated, they are a short course in the how’s and why’s of nonprofits in general and nonprofit news sites in particular.

This understanding becomes very important in the context of how nonprofit news sites develop and distribute their content. In the book, Connelly describes the practice of releasing the results of (the real) FairWarning through other respected news outlets with larger readership numbers. This is part of the cooperative way in which the new nonprofit news terrain works, but it does disadvantage portions of that supply chain, including operations like FairWarning, whose staff is small but powerful. Connelly himself believes that the specialization of sites is a good thing, allowing for deeper investigative reporting, but that this can also bring news organizations problems. Levin describes the conundrum:

ML: I would say certainly over 90 percent of our readers are somewhere else, and that is really good as far as reaching millions of eyeballs, because I know that we do, but it’s a little bit hard for kind of identity and brand, you might say. No matter how well labeled the story is by byline and tagline as far as who produced it, people tend to think of it as the work of wherever they read the piece. So, it creates some problems about kind of really developing an identity or a following.

I mean, I think most people who are avid consumers of news read stories like Fair Warning, but a lower percentage, if you asked them who FairWarning is, will be able to tell you exactly. So, that’s an issue, and it’s really critical if we’re going to matter. I mean, we’re a niche website. We’re never going to have a giant flow of traffic. The ultimate, biggest single goal is to get these stories out there, involve as many people as possible, so you can have an influence in terms of informing them and maybe influencing even the choices they make as consumers, businesses, or regulators.

You know, we think through that, but if it was just on our website, it would be really tough. We’ve had stories on our website that get a few hundred or a few thousand page-views, but because they ran on the whole McClatchy chain, millions of people saw them all over the country. So, it’s really kind of critical to us, just even for how we earn our daily bread, how we think of ourselves, what our morale is, to get the stories out there. In the book, aren’t I always selling stories to people?

Levin says the way philanthropic money is distributed in the new nonprofit news landscape does not entirely fit the need. Lately, he observes, the emphasis has been on local news sites, but there is a whole subfield of sites that do deep investigations in niche areas where coverage would otherwise be insufficient. These kinds of sites have been important sources of investigative news, including such outlets as The Trace, The Marshall Project, and Inside Climate News, all of whom have “angel” donors. Those without donors are often living hand-to-mouth, and this makes them work twice as hard for each dollar even while observing all of the ethical limits around sources.

The descriptions of this problem in the book have the fictional Myron Levin constantly distracted by the need to engage new donors even when murder and mayhem is occurring within one of his reporters’ investigations. He told me:

ML: One thing that comes across because of the—perhaps somewhat exaggerated—treatment of the amount of time the Levin character spends trying to raise money is that nonprofit work is really, really money-driven. I don’t know how obvious it is to other people. Many journalists, for example, in the traditional media where I worked before, metro daily newspapers, they were completely insulated from this, from the staffs of people selling ads and subscriptions and stuff. Now, all the well-intended advice we get to try and help us continue and grow is how to enlist your staff in your fundraising efforts.

He says that if you listen closely, you can hear how the lure of money is reflecting on coverage.

ML: Occasionally, if you listen to a public radio station, they’ll do their little story on something to do with an elementary school that has an art program or something, and you’ll hear somebody say something like, “Reporting on arts education, this is Mary Jones,” whatever. And you know, that’s not a real beat; there’s not an arts education beat anywhere even at the New York Times or the Washington Post. That is a donor that said, “I’ll give you 25, 50, $100,000 if you do at least three or four stories this year on arts education.” It’s not that it’s not a legitimate story; it’s just so far down the list of what the best stories are that we can do for our readers and ourselves. So, I’m not sure that people in the nonprofit world should be on a really high horse about how they manage all of this, but it is different.

For Levin, being in a work of (very) popular fiction has given him a chance to reflect on his life’s course.

ML: In nearly all of Mike Connelly’s books, there is a relentless truth-seeker (a homicide detective in the Bosch/Renee Ballard books, an investigative reporter in the McEvoy series) who routinely defies authority and ignores boundaries. As part of the quest, he/she finds clever ways to go over, under, around or through some hidebound bureaucrat who is wedded to traditions and enforcing the rules. In Fair Warning, the Levin character is sort of that guy….

Now, in my three decades as a reporter before starting FairWarning (with the Los Angeles Times, the Kansas City Star, the Rocky Mountain News), I was obstreperous, distrustful of authority, only marginally cooperative and, no doubt, to many people in management an all-around pain-in-the-ass. That is, I much more closely resembled Jack McEvoy than the Levin character who is trying to keep him on a leash. Yet, my character’s efforts to manage the reporter reflect the reality of my current role as the enforcer of standards for a small news organization.

And so, new images of consequential people are born and borne out through popular literature. In Connelly’s novel, which involves the misuse of DNA data and murder by “internal decapitation,” the nonprofit is not the story but the setting, and that setting is drawn with the right level of nuance to reveal the complex ethical and practical realities of the nonprofit news site. We hope it is one of many such attempts to normalize nonprofits through balanced and accurate treatment in literature and pop culture as a while.

We cannot always expect such portrayals to be complimentary, as is witnessed by Issa Rae’s excruciating representation of a modern-day colonialist organization cringingly named “We Got Y’all” in HBO’s Insecure, but they will help us all in extricating nonprofits from the circa-eighteenth-century characterizations that predominate in literature—and potentially from some of the real-life reflections of that illiteracy that persist because they are unexplored in literature and popular culture where we work out what we think and feel about things.

Connelly, for his part, is interested in how, in this case, art imitated life, which imitated art, remarking on the fact that the real FairWarning news site now covers DNA.