October 27, 2017; Vogue

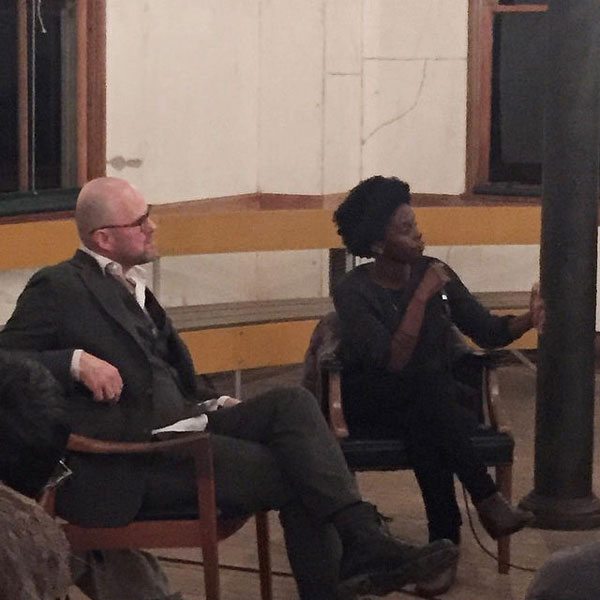

Toyin Ojih Odutola, a 32-year-old artist born in Nigeria and raised in the US South, opened her first solo museum exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art last month. Her conceptual portraits of wealthy, self-possessed Black people seek both to disorient the viewer and to invite questions about why these images would be disorienting to begin with.

Describing Odutola’s subversion of notions of presumed identity, Vogue’s Julia Felsenthal writes, “Odutola drawings operated as a sort of clever reversal: If all you see is skin, let me show you how I see it, as supernatural, transcendent, defiantly hyperrealistic.”

The series of interconnected intimate drawings seek to explore “the complexity and malleability of identity” by chronicling the lives of two aristocratic Nigerian families brought together by the union of their sons, two gay men. Homosexuality may be illegal in Nigeria, but black wealth is real; in the US, homosexuality is not illegal but aristocratic black wealth is unimagined.

These are dazzlingly colorful, large-scale (nearly life-size) portraits of richly dressed black individuals. Self-possessed, blasé even, they pose in lush interior and exterior settings, rendered in a sumptuous palette of ocher yellow, deep blue green, lavender, and millennial pink.

In Representatives of State, four female figures “stand in front of an arched window, gazing down at the viewer, regal and distant.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Odutola’s drawings play with anachronisms and anatopism—“angles that don’t make sense”—symbolizing incongruity in order to highlight “the most unnerving incongruity of all”: the lack of images of black wealth.

The context for these drawings is the election and presidency of Donald Trump. Odutola began the drawing series in 2016 and admits, “It started from a slightly angry place.” Watching the credibility afforded Trump because of his money and in spite of his lack of political experience made her think about wealth. She says, “What wealth affords us is the privilege to not care. Why would we want someone who has the privilege to not care being our president?”

Explaining her conceptual process, she continues,

One of the things I tried to inject into this series was constantly hearing about the mediocrity of white men, how that was no longer helping them move through the world. Because, yes, it’s a globalized, capitalistic system. You can’t just be mediocre. You can’t just fall back on your whiteness and your maleness as a thing that can get you ahead. You have to do a little more…Because everyone here is hustling just to be seen, and all of us have to be exceptional to do so. You have been unremarkable for a very, very long time. I wanted to show an unremarkability…But in order for me to create that piece, I have to be extraordinary. I have to work twice as hard to make this picture look unremarkable. That was what I was pushing at, what seeped in. Because I kept hearing it all summer, with all the statues, the protests, it was like, everyone is very angry. And I don’t understand where this anger is coming from. The people who should be angry are in Flint, Michigan.

But, she says, her concept of wealth evolved. “Yes, wealth was the starting point, but also a wealth of self, the notion of knowing that you can walk into a space and see these people in the most boring staid way that wealth affords.”

The exhibit will run through February 25, 2018. Check it out if you can.—Cyndi Suarez