August 11, 2020; Guardian

On August 11th, the Guardian and KHN (Kaiser Health News) launched Lost on the Frontline, an interactive database to document every healthcare worker who has died of COVID-19. Their goal is to “count, verify, and memorialize every US healthcare worker who dies during the pandemic.” So far, both news agencies have been able to independently verify the deaths of 167 health workers out of the 922 reported, and they have published the 167 names, photos, and stories of these health workers who have died while working on the frontline of the pandemic.

Readers may remember that it was the Guardian that in 2015 provided the first set of numbers for US police-involved shootings to try to counter the longstanding lack of collection or reporting of those statistics in the US. These kind of databases—established by media or groups of concerned citizens—are becoming increasingly critical elements of civil society.

As pictures of the numerous victims scroll across the top of the database, the Guardian and KHN ask, “Did they have to die?”

Across the US, COVID-19 cases remain high, and there is a continued and widespread shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) for healthcare workers. Days after the launch of the database, the Guardian also reported that US hospitals are pressuring their staff to work even when sick, forcing them to choose between their health and being paid. Many are returning to work while possibly still infectious.

The haunting question posed by the Guardian and KHN not only needs to be asked but also needs to be answered. And sadly, based on their independent reporting, the answer is that yes, many of these deaths were preventable and stemmed from inadequate preparation for the pandemic, which led to a lack of PPE; mistakes made by the government; and an already overburdened healthcare system.

As of mid-August, those lost include doctors, nurses, paramedics, hospital janitors, administrators, and nursing home workers. One of the very first victims documented by the database passed away in March: Alvin Simmons, 54, was a custodian in a New York hospital, a Gulf War veteran, and a grandfather of three, who had “turned his life around” and “loved helping people.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Utilizing reports from colleagues and family members, social media, online obituaries, unions, and local news media, more than 50 journalists from the Guardian and KHN spent “months investigating individual deaths to make certain they died from COVID-19, and that they were indeed working on the frontlines in contact with COVID patients or working in places where they were being treated.”

Beyond verification, the other major component of the investigation is looking into the circumstances of the deaths—in particular, the victims’ access to PPE. Although the database is still a work in progress, with the majority of deaths yet to be confirmed, early data suggest that dozens who died did not have access to PPE, including Simmons, who developed symptoms in March after cleaning a woman’s room who appeared to have COVID-19. After reporting his concerns, he received an email from a hospital spokesperson stating there was “no evidence to suggest that Mr. Simmons was at a heightened risk of exposure to COVID-19 by virtue of his training or employment duties.”

The journalists compiling data for the website discovered through their reporting that “many healthcare workers are using surgical masks that are far less effective than N-95 masks,” putting them in jeopardy, and “emails obtained via a public records request showed that federal and state officials were aware in late February of dire shortages of PPE.”

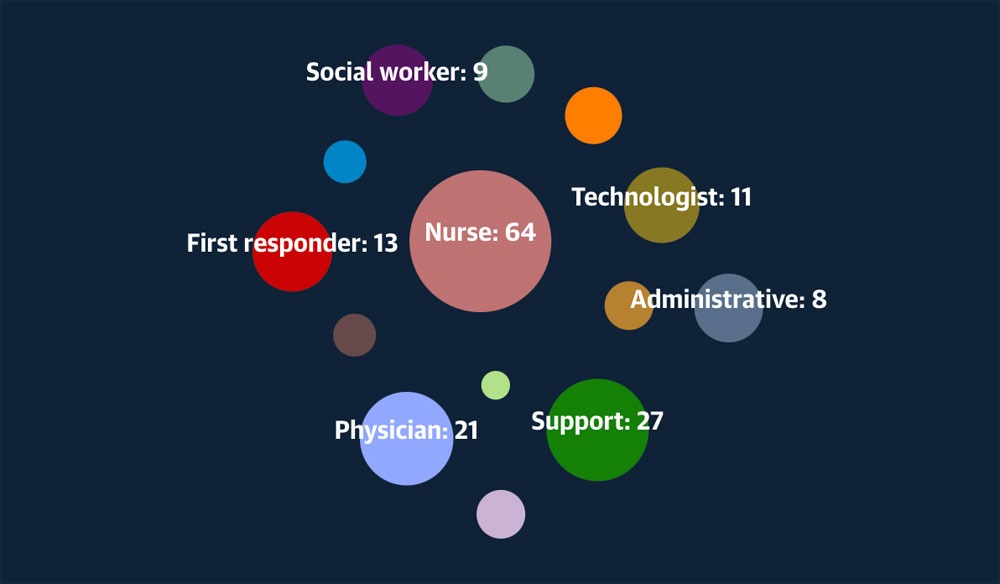

Early findings also indicate that over 20 percent of the victims died “after federal work-safety officials received safety complaints about their workplaces,” and that most victims have been people of color, many of whom were immigrants. Of the 167 victims currently memorialized on the database,

- A majority—103 (62 percent)—were identified as people of color.

- At least 52 (31 percent) were reported to have inadequate PPE.

- The median age was 57, and ages ranged from 20 to 80, with 21 people (12 percent) under 40 years of age.

- About one-third—at least 53—were born outside the United States, and 25 were from the Philippines.

- The majority of the deaths, 103, were in April, after the initial surge on the east coast.

- Roughly 38 percent—64—were nurses, but the total also includes physicians, pharmacists, first responders and hospital technicians, among others

- At least 68 lived in New York and New Jersey, two states hit hard at the outset of the pandemic, with Illinois and California following.

The need for independent reporting on and public accountability for the numerous deaths of healthcare workers is necessitated by shortfalls in government data. Two weeks ago, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 592 deaths but “conceded that this is an undercount” and did not list any victims’ names.

Whether it was Israel Tolentino, Jr., “a first responder with an ever-ready smile”; Lisa Ewald, a “nurse who loved animals [and] died alone at home”; Dorothy Boles, a “nurse and pastor [who] attended bodies and souls”; Bishop Bruce Edward Davis, who “practiced his faith in care of inmates”; or Helen Gbodi, a “single mom [who] dreamed of opening a nursing home”; Lost on the Frontline refuses to let these lives and the many hundreds of others who have died in service to their fellow Americans remain lost and unknown.—Beth Couch