August 12, 2015; Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation blog

Susanna Hegner reports for one of the nation’s absolutely top-notch rural foundations, the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation located in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, about a new report on the challenges facing black women and children in rural America, particularly in the rural South. In Unequal Lives: The State of Black Women and Families in the Rural South, researchers for the Southern Rural Black Women’s Initiative (SRBWI) looked at conditions in the Black Belt counties of Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. It shouldn’t be a surprise that the report found, “On nearly every social indicator of wellbeing—from income and earnings to obesity and food security—Black women, girls and children in the rural South rank low or last.”

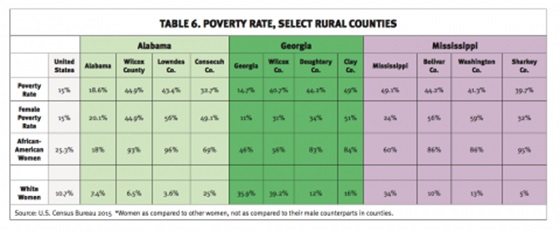

The findings aren’t simply that black women and their children live in abject poverty in the rural South, but the gap between their status and the conditions faced by other poor and non-poor people in rural areas is so huge, stark, and distressing. The following chart compares the poverty rates of all people, women, white women, and African-American women in the eight counties in the report.

If you are surprised by these statistics, then you might have missed streams of articles in the NPQ Newswire and elsewhere documenting the socio-economic inequities operative in this country by virtue of race, gender, family status, and rural location.

The report was funded by the Ford Foundation, Marguerite Casey Foundation, Foundation for a Just Society, and of course the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation, all recognizing the importance of an organization such as the SRBWI, with leadership including people like Shirley Sherrod, whose amazing work over the years has been mentioned in the NPQ Newswire several times.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Reports documenting horrendous social conditions and societal inequities are very useful, but the nonprofit sector is awash with them. The key is what they recommend as ameliorative actions and who is prepared to fund and implement them. These are the core recommendations of the SRBWI report:

- Support alternative enterprise development, along with job creation and training for low-income women and families in the rural south in occupations and fields with opportunities for career advancement and mobility.

- Provide targeted investments and tax incentives to small- to medium-sized enterprises and corporations for place-based alternative economic development.

- Support early links to the labor market for young Black women and men in the rural South.

- Expand work supports for low-income families in the rural South…such as transportation, childcare, and tax credits.

- Increase philanthropic investments in the rural South.

- Build the public infrastructure in the rural South by providing tax incentives and subsidies to small businesses and corporations.

- Alleviate food insecurity among low-income children in communities throughout the rural South by providing nutritious food in the summer and during school breaks.

- To reduce obesity in women and children, provide healthy food options in community-based health education programs.

- Provide health and recreation resources to rural communities to promote fitness, physical activity, and healthy lifestyle choices for children and families.

- Promote and provide reproductive health education in communities, schools and churches in the rural South to reduce early motherhood, infant mortality, and the transmission of STIs.

- Expand access to high quality childhood education for low-income children in the rural South.

- Improve school quality in rural communities by investing in teachers, technology, libraries, and supplies.

- Increase research and data collection on the impact of poverty on health outcomes for Black women and young women in the rural South.

Not surprisingly, these recommendations and the explanations in the report are not “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” ideas or solutions that can be carried to black communities by well-intentioned but poorly equipped temporary volunteers. These are issues requiring systemic solutions and policy changes that may be implemented at the local and state levels, but need federal resource commitments.

None of these policy changes will happen without a strong infrastructure of community-based and regional organizing and advocacy organizations that have the capacity to mobilize and challenge policymakers to respond to these issues. That takes the analysis back to the dearth of philanthropic support for rural advocacy. Although Mary Reynolds Babcock and a few others are stalwart funders of rural groups, for the most part, U.S. philanthropy is missing in action when it comes to rural needs. The report puts the issue politely, but the point still gets across:

“With the exception of support in the wake of Hurricane Katrina or other natural disasters, philanthropic investments do not flow easily to rural communities and programs in the South. The paucity of funding for rural nonprofits and institutions located in the Deep South means they must work harder and with fewer resources to meet the needs of low-income individuals and families with significant barriers to economic security and overall wellbeing.”

Most foundation dollars that do reach the rural South go to universities, hospitals, and the arts. Exceptionally little money flows to the Black Belt counties reviewed in this report, very little goes to the needs of black women and children in the rural South, and little goes to building an effective, sustainable advocacy infrastructure. The SRBWI report should be added to the litany of callouts to the philanthropic sector that for the people in poor rural communities, foundations are still lagging far behind what they can and should be doing.—Rick Cohen