“Nothing less than a death penalty by social deprivation” is how Stephanie Cacioppo, Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience at the University of Chicago, describes solitary confinement. And that is indeed what it was like for Kalief Browder, who endured two of his three years on Rikers Island in solitary, beginning at the age of 16. His alleged crime (of which he maintained his innocence and was never convicted)? Stealing a backpack.

During his 700 days in solitary confinement, Browder attempted to end his life several times. After his release, he struggled to acclimate and readjust. Even when he seemed to catch his stride, taking classes at Bronx Community College, the unfathomable toll solitary confinement had taken on his psyche was irreversible. On June 6th, 2015, Kalief Browder died by suicide—illuminating the reality that, even after a person’s release, the psychological torment that takes hold during solitary confinement often never lets go.

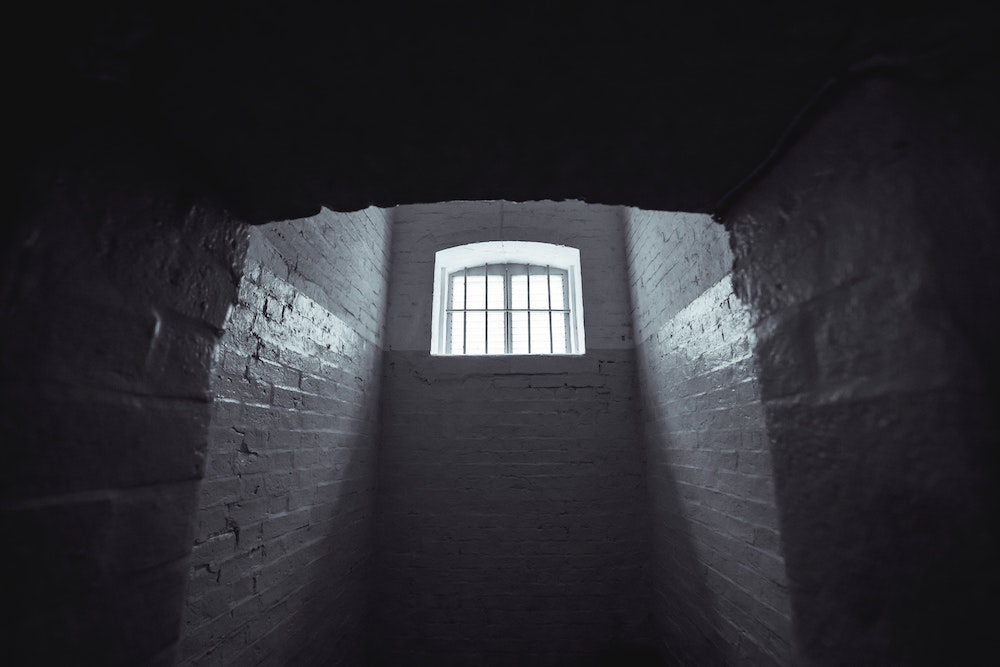

Right now, an estimated 80,000 individuals are languishing in cells no bigger than a parking spot, being subjected to severe sensory and physical deprivation for 23 hours a day, seven days a week.

Browder was far from an exception. Fifty percent of prison suicides are carried out by individuals in solitary confinement. This disturbing statistic begs the question: When a criminal “justice” policy drives half of those subject to it to end their lives, what purpose is it serving? Whose safety is it ensuring?

Solitary confinement is by no means implemented as a last resort. Incarcerated people are placed in isolation for a range of reasons—from committing violent acts to something as benign as being caught with a pack of cigarettes. The tactic has evolved into a means of control and has even been used to contain political activism in prisons. Right now, an estimated 80,000 individuals (according to available data) are languishing in cells no bigger than a parking spot, being subjected to severe sensory and physical deprivation for 23 hours a day, seven days a week. Such confinement can last for days, weeks, years, and even decades. It doesn’t matter if it’s called “isolation”: SHU (special housing units), administrative segregation, supermax prisons, the hole, voluntary or involuntary protective custody—they’re all the same barbaric practice.

Paramount to creating a more humane justice system—and therefore a more equitable and just society, free of systemic barriers—is eliminating the widespread use of solitary confinement, a practice that creates rather than mitigates harm. As President and Director of Programs of the Jacob and Valeria Langeloth Foundation, we work in pursuit of this vision. In the process, we have had the privilege of meeting people with direct experience with solitary confinement. Along with other leaders, these individuals are working tirelessly to dismantle the punishment paradigm to ensure that people return home as healthy, valued citizens and neighbors. Fundamental to this work is recognizing the humanity of everyone who comes into contact with the carceral system.

The Myth of Carceral Justice

The state-sanctioned torture that drove Browder and countless others to take their lives moved former New York Mayor Bill de Blasio to ban solitary confinement in New York City jails in June 2020. This victory was hard fought by countless prison abolitionists and reformists alike, and it seemed to be one small step toward divesting from punishment. The ban, which was initially delayed because of staffing issues at Rikers, is now in effect. The HALT Solitary Act prohibits incarcerated people from being held in solitary confinement for more than 15 days. However, data shows that the practice is still rampant in the state; 490 incarcerated people are being held in segregated housing, the average length of stay being 16.1 days.

How is this possible? Perhaps we can look to newly elected Mayor Eric Adams, a retired New York Police Department chief, who vowed to reverse this ban, refusing “to allow inmates and officers to be the victims of violent people.” But what about the victimhood of those subjected to solitary confinement? Classified as torture by the United Nations, solitary has never been shown to reduce violence in prison populations or increase safety for prison staff. We must push back on these punitive, tough-on-crime tactics that do nothing to mitigate harm, especially when their source is democratically elected officials.

Too often, elected officials like Mayor Adams—and increasingly, President Biden, who recently put out a call to “fund the police”—would rather maintain the status quo, even when insidious. Their positions and policies must be resisted. Performative centrism—where left-leaning politicians compromise moral standing for political capital—must be abandoned. We need advocates who leverage their power and access to transform the institutions that no longer serve us.

The executive order that President Biden released at the end of May highlights the need for more radical transformations of the criminal justice system. Its goal is “to advance effective, accountable policing and criminal justice practices that will build public trust and strengthen public safety.” Despite Biden’s 2020 criminal justice campaign platform, which promised to “end the practice of solitary confinement, with very limited exceptions such as protecting the life of an imprisoned person,” the executive order seems to fall short. Instead of making sweeping reform, it leaves reform in the hands of the Attorney General. Solitary Watch, a grantee partner and leader in the field, believes that Biden’s campaign promises won’t be fulfilled.

The myth that the carceral system keeps us safer has been debunked. However, President Biden continues to invest in it. Instead of deemphasizing prisons and the police state that perpetuates them, Biden’s newly proposed Safer America Plan is appropriating over $12.5 billion dollars to hire 100,000 new police officers throughout the country.

What does this have to do with improving imprisonment conditions? There are no prisons without the individuals who fill them. Policing and prisons work in concert with one another; to fully understand the scope of the devastation they inflict, they must be discussed in tandem.

Abolishing Solitary Confinement

It is no secret that Black and Brown communities are over-policed and under-funded. The country’s answer to societal ills like drug addiction and houselessness has been to disproportionately police communities that are historically (and presently) the most disenfranchised. Inadequate access to healthcare and mental health services, under-resourced schools, and a lack of economic stability, to name a few injustices, have created cycles of criminalization and poverty that fuel mass incarceration. Black men make up only 13.1 percent of the male US population, yet they make up 40.5 percent of the total male prison population and 43.4 percent of men in solitary.

There are individuals who are incarcerated right now that need relief. The daily suffering they face is not theoretical, but a tangible reality.

The long-term goal must be to abolish the criminal legal system as it currently exists. As a society, we need to re-envision systems that are steeped in racism, classism, and hyper-surveillance. This project, admittedly, will take years, if not decades, to implement. At the same time, we must recognize another pressing issue. There are individuals who are incarcerated right now that need relief. The daily suffering they face is not theoretical, but a tangible reality.

We need to fund communities most impacted by the carceral system to stop harm before it happens. Preventative, not reactionary, justice is crucial, and funneling more resources into people—and less into the prison industrial complex—is the solution. Yet, even as calls to defund carceral systems grow, for many, gut reactions still point towards revenge-based punishment. To invest in people we’ve labeled “criminals” and “felons” is to believe in their humanity and capacity for redemption. It’s to believe that justice lies not in “an eye for an eye,” but in restoration and transformation. That’s a scary prospect when you’ve been taught to get even with those who hurt you, not realizing that when we do so, we extend the cycle of harm.

Danielle Sered, founder of Common Justice, a long-time Langeloth grantee partner, describes the current violence the state enacts on incarcerated peoples in her book, Until We Reckon:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

To build the political will and expand these solutions, we have to stop talking about alternatives to our current policy as though they are alternatives to something that works. The question of whether to embrace a more dignified and humane approach to violence than the current system might be complicated if the current system were working. But when that system is failing, the burden of proof shifts. We should not be asking whether there is an appetite or opening for something new. We should be asking whether there is any moral or practical basis whatsoever for continuing with the old.

When a person is imprisoned, there is rarely closure for the victims of a crime. What is more, lengthy prison sentences do virtually nothing to rehabilitate incarcerated people and instead increase the likelihood that the same, or similar, violence will be perpetrated upon someone else.

Practices like solitary confinement are not only a detriment to incarcerated peoples’ mental health; even the shortest confinements increase recidivism and the chance that those confined will commit a crime again. Solitary confinement doesn’t even make prisons safer—on the contrary, programs like the Resolve to Stop Violence Project in San Francisco jails suggest that allowing incarcerated people full days out of their cells with social programming and engagement increases safety. We can look to other countries like Norway, which do not rely extensively on solitary confinement, for inspiration.

In Just Mercy, Bryan Stevenson asserts that we’re caught in a web of brokenness. We’re operating in a broken system that judges broken people who have broken and harmed others. But we’re all broken in some way. We’ve all been harmed and enacted harm. Our unwillingness to acknowledge the brokenness in ourselves allows us to deny the humanity of those whose brokenness has exceeded the limits of what we deem acceptable. As Stevenson asks, what if we “embraced our humanness, which means embracing our broken natures and the compassion that remains our best hope for healing?”

Reimagining an entire system of control will not happen overnight, but the process is not unfeasible. We can take steps right now to chip away at this harmful system, including a federal ban on solitary confinement and other punitive practices. It may feel like abolition is lightyears away, but dismantling solitary is one step towards it. Dedicated organizations that realize the urgency of these issues are already doing this work.

Activism Offers Glimmers of Hope

National campaigns like Unlock the Box—whose primary goal is to end solitary confinement—work with solitary survivors, family members, legislators, and advocates to shift the national conversation and hold policymakers and corrections leaders accountable for the human rights crisis at hand. Louisiana just passed Act 496 into law, eliminating the use of youth solitary confinement beyond a 24-hour period. Prior, solitary confinement was used as a means to “manage normal behavioral issues, drug abuse, and mental health disorders.” With Act 496 in place, solitary confinement can only be used in “cases where there is an extreme threat to life.” The California Mandela Act was set to ban the use of long-term solitary confinement and completely prohibit it for people who are pregnant, disabled, and under the age of 25 or over 65. Unfortunately, Governor Newsome vetoed the bill on September 30th, citing “safety concerns,” a myth proven to be false time and time again. We must push back on claims such as these, especially when they are used to strike down progress against cruelty or advance legislation that perpetuates harm.

One of Langeloth’s newest grantee partners, Worth Rises, is also working to dismantle the prison industry and the exploitation it generates. One of its most impactful projects as of late has been addressing the $1.2 billion prison telecommunications industry that capitalizes off the desire of families and their incarcerated loved ones to stay connected. Miami-Dade County was the most recent win in the battle against the prison telecoms industry. In April, the Miami-Dade Department of Corrections detailed its free communications plan, which includes 90 minutes of free phone calls daily, 120 minutes of free video calls weekly, and limited free electronic messaging. Connectivity between incarcerated people and their families is crucial, especially when one in 28 children have a parent in prison or jail. Additionally, family phone calls are shown to reduce the likelihood of recidivism and help promote healing while incarcerated.

Activists across religious traditions are organizing to end torture in US policy, practice, and culture at the National Religious Campaign Against Torture. In July, they advocated for members of the House of Representatives to co-sponsor the Solitary Confinement Study and Reform Act. This bill would create a bi-partisan commission, including formerly incarcerated individuals and their family members, to study the effects of solitary confinement. They also recently launched the National Network of Solitary Survivors, which provides peer support, mentorship, and leadership opportunities to individuals who have experienced solitary confinement.

A Langeloth grantee partner, Solitary Watch uses storytelling as their weapon against solitary confinement because public awareness is paramount. One of their projects, Lifelines to Solitary, combats the sensory and physical deprivations that long-term isolation causes through the only means of contact that can penetrate the walls: letters. They connect individuals living in solitary confinement with community organizations, faith communities, and student groups who want to provide solace, camaraderie, and a glimmer of hope in an otherwise desolate space.

Last year, The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), a member of the Federal Anti-Solitary Task Force, released the first ever blueprint for ending solitary confinement. It details how the United States government “can use executive, administrative, and legislative action to end the torture of solitary confinement in federal custody, including in Bureau of Prisons facilities, U.S. Marshals Service facilities, and immigration detention.”

The Center for Children’s Law & Policy is leading a national campaign, Stop Solitary for Kids, and recently launched a youth-led podcast, Not in Isolation: Voices of Youth. The show aims to elevate the voices of young people directly impacted by solitary confinement and incarceration and explore “how the punishment paradigm in the legal system tears at the fabric of our families and communities.” The third episode, entitled “One Too Many,” released in August.

Fortunately, many people have been imagining and organizing for decades—everyone just needs to listen.

Additionally, organizations like One Voice United and Amend are working from inside to transform correctional culture and give prison staff the chance to leverage their firsthand experiences to drive prison reform. These organizations recognize that “absent correctional staff input, or buy-in, reforms, no matter how well intended, will be much harder to implement and sustain.”

Reworking these systems will require imagination. Fortunately, many people have been imagining and organizing for decades—everyone just needs to listen. While the grantee partners listed above are leaders in the field, they are only a fraction of the movement. Incarcerated people have been advocating on their own behalf, even behind bars. Their voices, stories, and grassroots organizing laid the foundation for the solutions we see today. Johnny Perez, Director of US Prison Programs at NRCAT, said it best: “People are the experts of their own lives.” He reminds us that ‘‘when you see an ineffective policy, it’s usually because the voices of the most harmed are not being centered.” Those directly impacted by policies need to be on the frontlines of constructing those policies, or else policy gaps will go unnoticed.

As funders, it is time we amplify those on the frontlines by investing in the solutions they are creating, solutions that honor our collective humanity and divest from the harmful carceral state.