April 20, 2014; New York Times

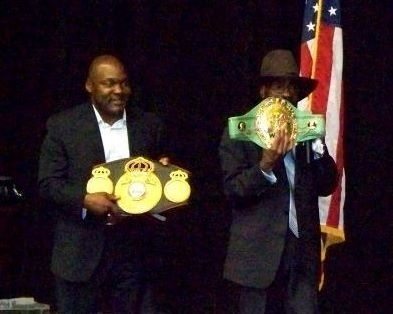

Over the weekend, Rubin “Hurricane” Carter died at the age of 76. Although he entered the consciousness of many more Americans when he was portrayed by Denzel Washington in an Academy-nominated role in The Hurricane, he was known to social activists for decades due to his having been wrongly convicted of murder and jailed for 19 years before the charges against him were dismissed.

The former middleweight boxer had been convicted in two jury trials for the murder of two men and one woman outside a bar in Paterson, New Jersey in 1966. The verdicts were overturned on grounds of prosecutorial misconduct, but he spent the next several decades trying to clear his reputation of the charges of murder. The charges were not formally and finally dismissed until 1988, 22 years after they were first filed.

Carter had a very tough, troubled childhood, with plenty of interactions with the law. He spent time in reform school, and later had jail time before and during his career as a top-level prizefighter. But that didn’t make him guilty of a murder for which the two witnesses later recanted their testimony. After being convicted in the second trial, Carter told the New York Times, “They can incarcerate my body but never my mind.” He maintained his innocence and became recognized, inside and outside prison, as a civil rights advocate and champion. Nelson Mandela actually wrote the foreword to Carter’s 2011 autobiography, Eye of the Hurricane: My Path From Darkness to Freedom. The brilliant New Jersey judge who overturned the second of Carter’s convictions, H. Lee Sarokin, said it best: Carter’s conviction had been based on “racism rather than reason and concealment rather than disclosure.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Not long after his exoneration from the Paterson murder charges, Carter institutionalized his campaign against the wrongful imprisonment of people like himself and his co-defendant, John Artis. In 1993, he was recruited by Win Wather in Toronto to serve as executive director of the nonprofit Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted, which Carter led through most of 2004. Although the organization fought for and obtained the freedom of a number of Canadians during that time, Carter left AIDWYC in 2004 because five of the 20 AIDWYC board members refused to join him in opposing the appointment of Judge Susan MacLean to the Ontario bench because of her earlier role in the prosecution of a man convicted in the murder of a nine-year-old girl but later exonerated by DNA evidence. The press coverage of Carter’s disassociation with the organization suggests a dynamic of combined acrimony and befuddlement within the board and between the board and Carter.

After leaving AIDWYC, Carter founded another nonprofit in Canada, Innocence International, with a similar mission and a track record of speaking out on behalf of people it believed to have been wrongly tried and convicted. One high-profile case Carter and Innocence International took on was that of Sebastian Burns and Atif Rafay, who were convicted in 2004 of the murder of Rafay’s father, mother, and sister a decade earlier. It isn’t clear whether Innocence International still exists— links to the Innocence International site seem to be broken, though reports about Carter’s frequent speeches as the founder/director of the organization are available through Google searches—but Carter’s papers will be sent to the Rubin Carter/John Artis Innocence International Project at Tufts University outside Boston.

Although long disassociated with Carter and apparently barely in contact, AIDWYC published a blog post honoring Carter on the announcement of his passing:

“Rubin will be remembered by those at AIDWYC who were fortunate enough to have worked with him as a truly courageous man who fought tirelessly to free others who had suffered the same fate as he. We are honoured that Rubin played a significant role in the history of our organization. We will continue to fight against wrongful convictions, a battle that Rubin valiantly fought until the day he died.”

Carter passed away estranged from some of his family members and from his colleagues at AIDWYC. But his message in promoting the reconsideration of convictions in the U.S. and Canada, making people think twice about possibilities of prosecutorial bias and misconduct, especially around matters of race, is still current and alive.—Rick Cohen