May 30, 2014; Reader Supported News (The Guardian)

In the upcoming Council on Foundations conference, there will be a session to address the intersection of the First Amendment and freedom of speech. It is an important topic, though the description omits the biggest challenge to nonprofits’ free speech rights—in fact, the free speech rights of all Americans: the generally unconstrained and probably unconstitutional surveillance of telephone and Internet communications by the National Security Agency.

Equally important, however, is the treatment of Edward Snowden, who blew the whistle on the NSA’s surveillance practices. Snowden faces trial and potential conviction under the Espionage Act. Many politicians of both political parties have made it clear that they consider Snowden a traitor of the first order, even though his revelations have led to a national dialogue on free speech and privacy issues. Even while denouncing Snowden, President Obama announced some minimal changes in NSA policies, and since then Congress has taken up legislation ostensibly intended to rein in some of the more egregious of the NSA’s metadata collection policies.

In an unusual tactic, Secretary of State John Kerry has repeatedly compared Snowden with Daniel Ellsberg of “Pentagon Papers” fame. In one interview, Kerry called Ellsberg a patriot but Snowden a “coward,” a “traitor,” and someone who had “betrayed his country.” In another recent interview, Kerry called on Snowden to “man up” and “face the music” for his alleged violations of the Espionage Act.

As a former assistant district attorney in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Kerry must assuredly know that his statements are unlikely to convince Snowden that he has much of a chance of getting a fair trial in the states. But the more interesting part of Kerry’s ploy is in comparing the “unpatriotic” Snowden with the “patriot” Ellsberg.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

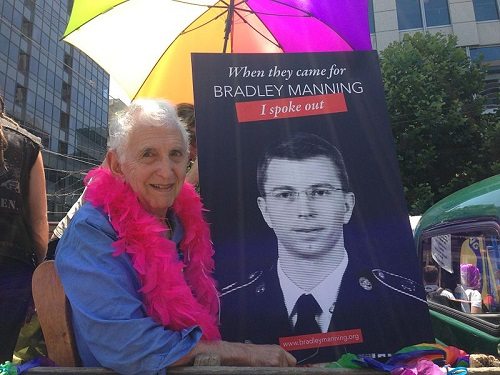

For a number of reasons, Ellsberg is convinced that “until the Espionage Act gets reformed, [Snowden] can never come home safe and receive justice.” Ellsberg notes that were he to return to the states, Snowden “would come back home to a jail cell—and not just an ordinary cell-block but isolation in solitary confinement, not just for months like Chelsea Manning but for the rest of his sentence, and probably the rest of his life.” Snowden’s chances of getting bail would be just about zero, compared to his own circumstances during his indictment for the release of the Pentagon Papers when he was out on bond for the entire 23-month period.

He also points out that “the current state of whistleblowing prosecutions under the Espionage Act makes a truly fair trial wholly unavailable to an American who has exposed classified wrongdoing…Snowden’s own testimony on the stand would be gagged by government objections and the (arguably unconstitutional) nature of his charges.” In the article, Ellsberg provides snippets from his trial that would give Snowden or his attorney little hope of being able to present their case.

Of course, Ellsberg might have simply discussed the Obama administration’s track record of unparalleled prosecution of government whistleblowers no matter where they come from. Snowden has caused the Obama administration untold difficulties, with the NSA and other government leaders making statements that were clearly false about the government’s snooping. It is difficult to imagine that the political impact of Snowden’s revelations would be easily disentangled from a potential Espionage Act prosecution.

“John Kerry’s challenge to Snowden to return and face trial is either disingenuous or simply ignorant that current prosecutions under the Espionage Act allow no distinction whatever between a patriotic whistleblower and a spy,” Ellsberg concludes. “Either way, nothing excuses Kerry’s slanderous and despicable characterizations of a young man who, in my opinion, has done more than anyone in or out of government in this century to demonstrate his patriotism, moral courage and loyalty to the oath of office the three of us swore: to support and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

It is important for nonprofits to discuss the status of potential regulations concerning the political activities of 501(c)(4) social welfare organizations, campaign finance legislative proposals, and the implications of the Supreme Court’s Citizen’s United and McCutcheon decisions. But for a discussion of “fundamental freedom of speech issues from different angles,” the COF program ought to also examine the issues raised by the revelations of Edward Snowden—his potential status as a “traitor,” in Kerry’s words, or as “the greatest patriot whistleblower of our time,” to use Ellsberg’s characterization—and the meaning for nonprofits of the governmental policies and practices that Snowden revealed.—Rick Cohen