February 27, 2013; Source: Center for Global Development

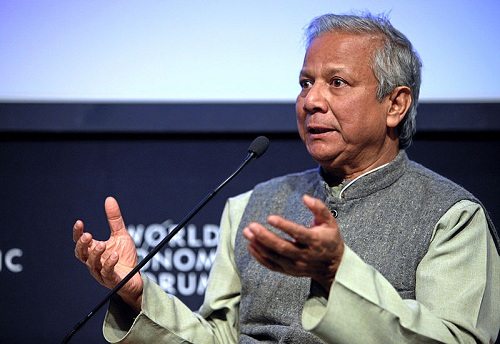

Among organizations operating largely overseas, one that is well known among Americans and generally quite respected is the Grameen Bank, which was founded by Nobel Prize winner Muhammad Yunus. The positive image and reputation of Grameen and Yunus haven’t suffered much in the U.S. despite occasional criticisms and challenges (for example, see the pretty devastating critiques by author Arundhati Roy and economist Jagdish Bhagwati). Yunus no longer runs Grameen, having been forced out or, more politely, “retired” by the Awami League government of Bangladesh.

Writing for the Center for Global Development, David Roodman suggests that the post-Yunus Grameen might not even survive. The Dhaka government created a commission that reported harsh findings in 2011 about the bank under Yunus’s direction, but Grameen continued its work. Last month, a second commission released a report, this one focusing on whether Grameen was legally organized and whether the board had exercised appropriate oversight.

Roodman cites some of the second commission report’s toughest conclusions and recommendations:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“The nine female member-borrowers on the Grameen Bank’s board should resign immediately. The Bank should un-invite 90% [of] its members by buying back their shares. The remaining 10% should elect new board members, with only those who have completed 7th grade eligible to run. The license to operate a digital mobile network held by Grameenphone, Bangladesh’s largest phone company, should immediately be suspended—but as a matter of practicality, the firm should keep operating.”

Additionally, the report asserts that Grameen’s sales of shares to more members were illegal and should be bought back and that Grameen’s support of those other than the landless poor in rural areas was illegal because it strayed from the bank’s official mission.

There were some valid criticisms in the report, according to Roodman, that the board was ineffectual, as is the case with many founder-led boards. The nine women borrowers on the Grameen board, despite constituting the board’s nominal majority, “could not be expected to understand the octopus-like complexity of the Grameen family of companies, assuming they were apprised of it…could not be expected to perform appropriate oversight….hardly ever said anything at the meetings beyond pleasantries.”

Nonetheless, Roodman says that the commission didn’t discover Yunus to be corrupt and didn’t find anything that the organization “illegally” did as meant for anything other than social good. At worst, it concluded that Grameen suffered from what we would call founder’s syndrome. The charges that Grameen strayed beyond its mission and legal authorization seem to be picayune overreadings of the laws under which Grameen operated—laws that were enacted, by the way, during the period of martial law in Bangladesh. Those laws, in their entirety, have been declared null and void by the Bangladeshi courts. To hold Grameen guilty of violating laws that have been undone by the post martial law government of Bangladesh would be Kafkaesque.

In the end, Roodman acknowledges some of the good points of the commission report while criticizing its biases and inaccuracies. But he concludes, “The poverty of most Bangladeshi’s being urgent, the eagerness of outsiders to work with the Grameen Bank being great, and the dangers of dependence on the government being obvious, it is understandable that Muhammad Yunus and others at the Grameen Bank pushed the limits of their independence in searching for ways to make a difference.” But with the elimination of Yunus from the Bank’s leadership, the failure to appoint anything other than an interim leader in his place, and the continuing criticisms from the Dhaka government, Grameen’s long-term prospects must be seen as somewhat shaky. —Rick Cohen