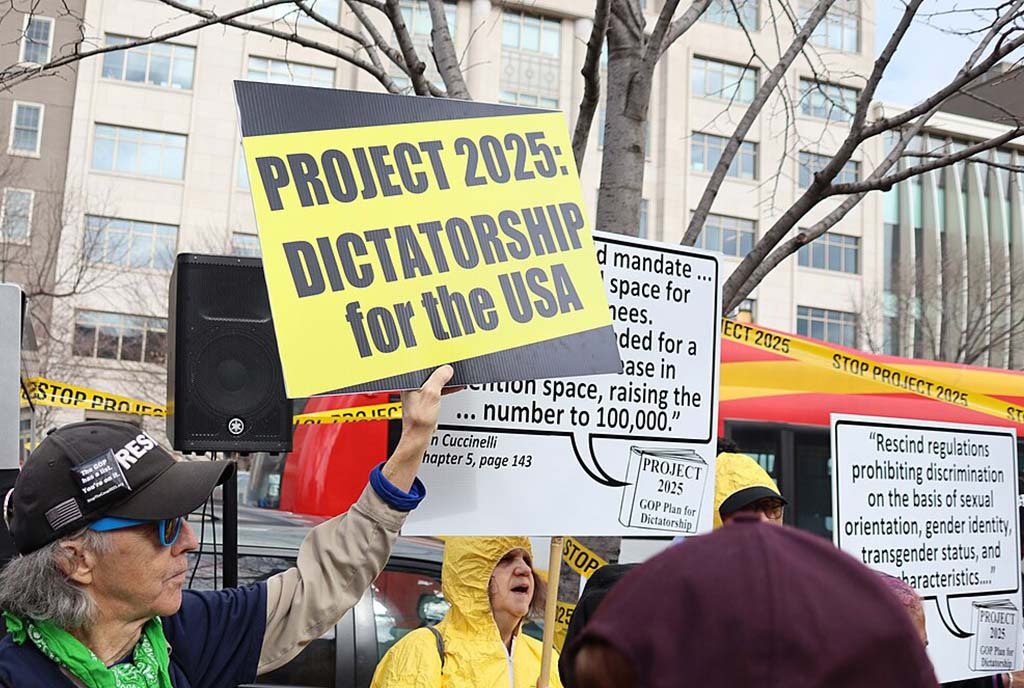

Rarely has a thinktank report gotten as much attention as Project 2025, which has sparked national conversation and was widely critiqued at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Published by the Heritage Foundation and formally titled Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise, the nearly 900-page document, divided into 30 chapters, offers a host of right-wing policy recommendations.

The document has been widely described as a “blueprint” for a possible incoming Donald Trump administration. That is not quite accurate. Authors disagree with each other: One writer (Kent Lassman) argues for free trade, while another (Peter Navarro) argues for the opposite position of high tariffs. Two writers also go head-to-head on whether the Export-Import Bank should be abolished or expanded.

Nonetheless, the document provides an important window into the policy thinking of an elite group of what Heritage describes as “more than 400 scholars and policy experts from across the conservative movement and around the country.” In the document, CBS News identifies 735 policy proposals, at least 270 of which correspond with policy positions publicly taken by Trump. Of the 30 chapters, 25 have lead authors who held policy positions in the Trump administration.

It is also worth noting that the policy document is only one part of a four-part operation. The other three parts are a personnel database of possible appointees, a training program (some disturbing videos published by ProPublica are here), and an unpublished confidential 180-day “playbook.”

Of the 30 chapters, 25 have lead authors who held policy positions in the Trump administration.

It’s impossible in one article to summarize 735 policy positions. The document is wide-ranging. For starters, among the proposals that Heritage’s own “debunking the lies” website lists as being “true” are: end DEI (diversity, equity & inclusion) protections in government, promote and expedite capital punishment, outlaw pornography, use public taxpayer money for religious schools, shut down the US Department of Education, mass deportation of undocumented immigrants, (largely) deregulate big business and the oil industry, and increase Arctic oil drilling.

Here, I will dig a little deeper into some aspects of the document itself, especially education, housing, labor, tax, and regulatory policy.

Education: Beyond winding down the Department of Education as a whole, there are specific recommendations regarding student loans. For instance, in the chapter on education (Chapter 11), Lindsey Burke, who directs Heritage’s Center for Education Policy, writes that the “The Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, which prioritizes government and public sector work over private sector employment, should be terminated” (354). Eliminating that program could harm the lives of over a million nonprofit and public service workers who carry student loan debt. Burke further calls for consolidating all student loan programs into a single program that utilizes income-driven repayment and “includes no interest rate subsidies or loan forgiveness” (354).

Interestingly, Brooks Tucker, author of Chapter 20 on Veterans Affairs, calls on the federal government to leverage student loan forgiveness to facilitate veteran hiring (652)—additional evidence, if more were needed, that Project 25 is far from a clear blueprint.

In terms of K–12 education, Burke advocates eliminating all competitive grant programs and reducing spending on formula grant programs for Title I (low-income) schools by 10 percent (360–61). Burke also calls for eliminating a key college pipeline program for low-income students—Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs (GEAR UP)—under the dubious theory that “it is not the responsibility of the federal government to provide taxpayer dollars to create a pipeline from high school to college” (361).

Burke also advocates using federal state power to shape higher education curricula by, for example, calling to “wind down” area studies programs, which, “although intended to serve American interests, sometimes fund programs that run counter to those interests” and replace that with “a new regulation to require the Secretary of Education to allocate at least 40 percent of funding to international business programs that teach about free markets and economics and require institutions, faculty, and fellowship recipients to certify that they intend to further the stated statutory goals of serving American interests” (356).

One other matter: Head Start, a pre-kindergarten program that enrolls over 850,000 children a year, is housed in the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS). Roger Severino, a former Trump administration official in the department who authors the HHS chapter (chapter 14), advocates for eliminating the program (482).

Housing: The Project 2025 chapter on housing is authored by a familiar name, none other than the former US Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Secretary Ben Carson. One step Carson advocates is to reduce civil service protections by replacing senior professional staff with political appointees. As Donald Devine, Dennis Dean Kirk, and Paul Dans (former director of Project 2025) write in Chapter 3 (“Central Personnel Agencies: Managing the Bureaucracy”), the Trump administration issued Executive Order 1395724 toward the end of 2020 to make career professionals subject to replacement by political appointees; this was reversed by President Joe Biden; the authors call for its reinstatement (80–81).

Researchers at the Brookings Institute estimate that this measure could increase the number of political appointees from 4,000 to over 50,000. At HUD, Carson calls on a new administration to “change any current career leadership positions into political and non-career appointment positions; and use Senior Executive Service (SES) transfers to install motivated and aligned leadership” (508).

Carson also calls for reversing recent measures that seek to reduce racial disparities in the real estate appraisal system. As Andre Perry noted in NPQ, national appraisal research has revealed that “on average, owner-occupied homes in Black neighborhoods are undervalued by $48,000 per home, for a cumulative loss of household wealth of $156 billion.” The Biden administration formed the Property Appraisal and Valuation Equity (PAVE) Task Force to address this. Carson calls on HUD to “immediately” dismantle PAVE and “reverse any Biden Administration actions that threaten to undermine the integrity of real estate appraisals” (508).

Carson further calls for repealing “the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) regulation” (509). As Lisa Rice of the National Fair Housing Alliance wrote in NPQ, “The AFFH provision requires entities—including cities, states, and housing providers—to conduct equity analyses to identify impediments that preclude people from accessing fair housing opportunities and living in healthy, well-resourced communities.…The AFFH mandate then requires entities receiving federal funds to develop and implement meaningful solutions and strategies for overcoming fair housing barriers.”

In short, Carson’s proposals, if adopted, would likely expand the nation’s gaping racial homeownership gap. Carson also calls for ending “housing first” (509) “so that the department prioritizes mental health and substance abuse issues before jumping to permanent interventions in homelessness”—a policy change that, if it were implemented, would surely increase US homelessness considerably.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Labor: The Project 2025 chapter on labor (Chapter 18) is written by Jonathan Berry, who led the US Labor Department’s regulatory office for Trump. Berry not only calls for eliminating DEI in labor policy but also wants to ban using “disparate impact” analysis that seeks to curtail racial discrimination (583). In 2019, when the Trump administration was making a similar attempt to bar the use of statistical analysis to identify discriminatory patterns, Sarah Hinger of the American Civil Liberties Union asked rhetorically, “If no one tells you they’re discriminating, is it still discrimination?” Her conclusion: if the use of disparate impact analysis were banned (as the Trump administration was then seeking to do), then the answer would necessarily be “no.”

Berry further writes, “The President should make clear via executive order that religious employers are free to run their businesses according to their religious beliefs, general nondiscrimination laws notwithstanding” (586), effectively giving free license for religious institutions to discriminate in hiring. More broadly, Berry also calls for “rescinding regulations prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, transgender status, and sex characteristics” (584).

Perhaps the idea here is that if no data is collected, the problem does not exist.

Not surprisingly, Berry also offers many policy recommendations that would restrict union rights—such as by making it easier for employers to classify workers as independent contractors (591); legalize company-dominated unions (599), which have been banned in the United States since 1935; bar employers, even if a majority of workers sign union cards, from voluntarily recognizing a union without holding an election (603); make it easier for workers to decertify a union (603); and end prevailing wage rules that protect construction worker wages on federal projects (604), to name just a few recommendations.

Taxes: Unsurprisingly, the chapter on the Department of Treasury (Chapter 22)—authored by William L. Walton, Stephen Moore (an advisor to Trump’s 2016 campaign), and David R. Burton—consists largely of recommendations to lower taxes on the wealthy, while (effectively) raising taxes on those of more modest means.

The measures proposed include reducing the corporate income tax rate from 21 to 18 percent and replacing the current income tax system, which has rates ranging from 10 to 37 percent, with a two-tier system of rates at 15 percent and 30 percent. The authors also call for the repeal of “all tax increases that were passed as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including…the stock buyback excise tax, the coal excise tax, the reinstated Superfund tax, and excise taxes on drug manufacturers” (696). For good measure, they advocate reducing the estate tax rate from 40 percent to 20 percent (697) while keeping the amount excluded from any estate tax at $12.9 million (it’s scheduled to drop to $5 million in 2026).

The coup de grace is a recommendation to require a three-fifths supermajority in both houses of Congress to raise taxes (698). This would “create a wall of protection for the new rate structure”—or, in other words, make it much harder to fund government services.

Financial Regulation: Chapter 27 examines two agencies: the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). Burton, who was one of the tax chapter authors, writes about the SEC, calling for 1) prohibiting “the SEC from requiring issuer disclosure of social, ideological, political, or ‘human capital’ information” that is not “material” to investors; 2) repealing “Dodd-Frank mandated disclosures relating to conflict minerals, mine safety, resource extraction, and CEO pay ratios;” and 3) opposing “efforts to redefine the purpose of business in the name of social justice” (832).

For his part, Robert Bowes, a Trump administration housing official, calls for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to be abolished (839) and to abolish the Section 1071 rule that aims to finally generate demographic data on small business lending.

Project 2025 in Context

The above only skims the surface. There is plenty more. For example, in Chapter 21, which covers the US Commerce Department, Thomas Gilman, who served in the department under Trump, writes that the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration “has become one of the main drivers of the climate change alarm industry and, as such, is harmful to future US prosperity” (675) and should therefore be dismantled (664). Perhaps the idea here is that if no data is collected, the problem does not exist.

Two things are true: 1) A lot of what is written will never make it into law, and 2) too much of it may well.

Occasionally, one finds an interesting wrinkle. For example, in an otherwise scary chapter on HHS, Severino writes, “We must shut and lock the revolving door between government and Big Pharma. Regulators should have a long ‘cooling off period’ on their contracts (15 years would not be too long) that prevents them from working for companies they have regulated. Similarly, pharmaceutical company executives should be restricted from moving from industry into positions within regulatory agencies” (452). Alas, such admissions of corruption are rare. Also, the policy solutions recommended generally serve to strengthen the private power that leads to the very corruption of public purpose of which Severino rightly complains.

How should one think of Project 2025 as a whole? It’s not unique. The Heritage Foundation has been producing similar reports quadrennially since 1980; their first helped inform Ronald Reagan’s administration. Heritage claims the Trump administration implemented 64 percent of its recommendations for 2017.

Not every Heritage guidebook is alike. The 2017 guide had 334 recommendations; this one has an estimated 735. Sometimes, like this year, there’s a tome of nearly 900 pages; by contrast, the 2005 edition was only 156 pages.

What to make of this year’s plans? Two things are true: 1) Much of what is written will never make it into law, and 2) too much of it may well. Even if Trump loses in November, as long as one of the leading US political parties has activists who hold positions like those outlined here, the risk will persist.

Bottom line: Project 2025 has gotten a lot of attention, and it’s important to know about its provisions. But for those of us involved in progressive social change work, it is even more important to develop plans of our own.