February 17, 2017; New Yorker

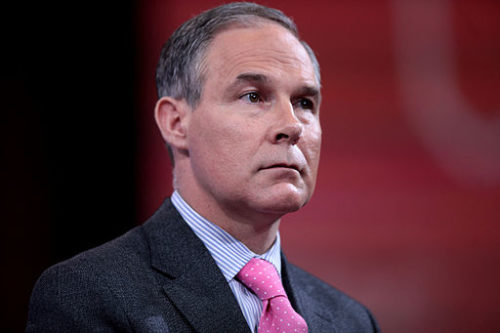

As journalist Amy Davidson reported Friday, February 17th, in her New Yorker piece, “Scott Pruitt, the EPA, and the Republicans’ Bargain with Trump,” the Republican-controlled Senate, as expected, rushed to confirm Scott Pruitt’s nomination last week as head of the EPA by a vote of 52 to 46, despite urgent efforts by Democrats and public interest groups to halt the vote until this Tuesday, the deadline for the court-ordered release of a trove of emails between Pruitt and the fossil fuel industry during the former’s tenure as Oklahoma Attorney General. Many public officials and interest groups unaffected by the cozy aura of ignorance surrounding Congressional Republicans suspected these emails would show Pruitt’s longstanding collusion with several legacy energy companies to undermine the missions of the EPA and environmentalists, including fighting hand-in-hand against climate change science and activism.

Earlier this week, the Center for Media and Democracy published its initial review of these emails, showing that collusive efforts were indeed legion. Pruitt emails released on Tuesday show several coordinated efforts against environmental protection efforts, including joint efforts in 2013 by the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM) lobbying group and Pruitt to fight two key EPA initiatives, the Renewable Fuel Standard Program and targeted ozone limits. AFPM provided text for official use by the state attorney general, writing Pruitt bluntly, “This argument is more credible coming from a State.”

Other emails show intimate bonds between Pruitt and Oklahoma City-based multinational corporation Devon Energy. The latter apparently ghostwrote letters for Pruitt challenging the EPA’s efforts to limit methane from oil and gas fracking. Devon also played matchmaker between Pruitt’s office, the conservative Federalist Society, and coal industry lawyer Paul Seby to lay the groundwork for a “clearinghouse” that would “assist AGs in addressing federalism issues”—that is, force the federal government to roll over and give their stick of authority over energy issues back to the industry-friendly states.

Davidson described the Senate vote as largely along party lines, with Susan Collins of Maine the only Republican to buck her party, while two Democratic senators from oil- and gas-rich states—Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota—voted in favor of Pruitt. Davidson opined that the Republicans may feel compelled to ride Trump’s wave of appointments out of concern for their individual and their party’s self-preservation. (She writes of their “floppy pose of deference” to the president.) That’s in spite of, or perhaps even in respect to, their seeming intent to invert the missions of key federal agencies, bending and reshaping them in the manner of M.C. Escher.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Last Thursday, in his first interview since his nomination in November, Pruitt spoke of executing the EPA’s mission forcefully while hewing to federal statutes rather than executive power-grabbing through expansive regulations, saying, “This past administration didn’t bother with statutes.” He discussed the need to defer to states’ rights to steward the environment within their borders: “Congress understood that a one-size-fits-all model doesn’t work…state departments of environmental quality have an enormous role to play.” Further, he held that promotion of jobs and business is not mutually exclusive with preserving America’s lands and natural resources:

We are blessed with great national resources, and we should be good stewards of those. But we’ve been the best in the world at showing you do that while also growing jobs and the economy.

Pruitt was a seasoned adversary of the EPA as Oklahoma’s attorney general. He sued the EPA in his official capacity a baker’s dozen times to block added protections to the Clean Water Act and other mandates within the agency’s purview. He now dismisses the threat of a new wave of suits against his anticipated anti-environmental policies, citing a widely accepted view of the courts’ strong deference to agency implementation of governing laws: “we protect ourselves by hewing to the statutes. It will prove very difficult for environmental groups to sue on the grounds that they think one priority is more important than another—because that is something that really is at the discretion of agency.”

Pruitt’s vow under Trump’s strident law-and-order philosophy to eschew overreaching regulations and strictly follow statutory mandates can be taken as he wishes it to be taken—that is, he (and, by proxy, Trump) is more concerned about deference to the legislative and judicial branch authorities than Obama and his appointees were. But it can also be taken as a signal that he will use his discretion to refrain from vigilant policing of industries and behaviors that risk harm to the environment.

At his speech on Tuesday, Pruitt gave a rosy historical context to his concept of harmonizing environmental and industrial interests, congenially recounting a “Founding Fathers” story of compromise that lead to moving the capital from New York to what’s now Washington, D.C. The problem, as Forbes contributor Eric Mack notes, is that those historical negotiations were about “elected officials trying to compromise with other politicians to get bills passed,” whereas the EPA’s mission is statutory and uncompromising about environmental protection: “To protect human health and the environment—air, water and land.” Pruitt is starting out of the gate with pro-energy concepts that may go beyond appropriate executive branch room-for-interpretation and, if implemented, could on their face be deemed illegal.—Louis Altman