“They who pay the pipers call the tunes.”

For the nearly two decades that I worked in the nonprofit sector, this truism riled me. It wasn’t so much that it was true, since it obviously was. It was more that both sides so readily accepted it and behaved accordingly. That meant, of course, that no matter what I knew about my work, or how much experience I had, the “funder” would determine how the funds I needed would be spent. I was a supplicant, not a partner, and certainly not a peer. My role was to accept with gratitude, back out, and move on to the next encounter.

Then, in 2000, I got a call out of the blue from a headhunter asking if I was interested in applying for a job as a program officer at a newly formed foundation in town (actually, a new iteration of an old foundation). I had come recommended, and they were interested in talking with me. At the time, I was working in community health for a large healthcare system, and was relatively happy and hadn’t been looking for work. But I figured, what the hell? At worst, I’d end up with a clean interview suit and an up-to-date resume.

And so it happened that I joined “the dark side” and became a program officer for the John R. Oishei Foundation. Oishei (pronounced “O shy”) had invented windshield wiper blades in 1917 and formed the Trico Corporation, which had become one of the largest employers and most successful companies in Buffalo history. The founding board of directors of the Foundation had come from careers in business and was, for the most part, conservative, successful, and interested in building Buffalo back to the level of its greatness during the earlier part of the 20th century. Each member had served on boards of directors of a variety of significant nonprofit organizations over many years, and had given much, both personally and professionally, to the region’s growth.

When I first started in philanthropy, there really were very few people in the sector who had had nonprofit management experience. Most of the people I worked with were much like my board: businesspeople with board experience and a determination to help fix the nonprofit sector. This was an overriding national theme: The nonprofit sector was undisciplined, untrained, wasteful, and inefficient. It needed “professionalizing.” It needed accepted business practices of accountability and goal achievement. It was considered Philanthropy’s duty to impose these corrections through the strategic use of grant funds, and that led to a series of efforts to achieve this on a national level, among them the creation of various sets of proposed “standards,” business plans, strategic plans, capacity building—all manner of approaches to tame the wild beast of nonprofit management.

After experiencing the crossover, and in coming to better understand the attitudes and frames of reference for both sectors, it is my experience that both the nonprofit and the philanthropic worlds have great difficulty giving up the habits of supplicant and bestower. “Calling the tune” is unquestionably a position of power; the dancers dance or they go home. When I first started at the foundation, my then-boss told me that I’d never pay for lunch again, and I’d never get an honest compliment (so don’t start believing my press). He didn’t mean this in a condescending way; it really was a statement of fact to him. Each side of this interaction had scripts; each role was determined. They came and asked; we said yes or no. Why we said yes or no was not questionable. We said one or the other, and that was it. The only way for the supplicant to influence the outcome was to somehow gain favor or positive attention—and it was anticipated that they would try to do so. In essence, the supplicant comes into each negotiation having already lost, and looking to get whatever is left that they can.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Many of my personal relationships changed when I began working in philanthropy, and I would say that most of those changes were not for the better. Of course, it’s easy to say that the ones that changed for the worse were already strained, or more in the “acquaintance” category, and that was no doubt true. But it still surprised me when I felt the expectation to act and respond in certain ways by people I had known and worked with for some time. I had never been in a position of such influence before, so that likely had much to do with it. It was foreign to me to be treated as a “guardian of the gold” and I was actually very reluctant to dance that dance with former colleagues. And I knew they were just as reluctant, but they had bills to pay (that I didn’t have anymore) and so they adapted to it much more quickly.

But it brought into much sharper relief for me the nature of the human interaction between grantmaker and grantseeker. No matter what I said about my benevolent or collaborative intentions as a grantmaker, my grantseeking colleagues would be watching and listening for “The Clue” that would unlock the secret to getting funds from us. “But you said if we did this…” It was and is as frustrating for them as it is for me. And because many of my philanthropic colleagues either accept or do not see this dynamic, the imbalance of power is routinely reinforced.

Many people—on both sides—believe that all is as it should be. It is the way of Money, and “it is what it is,” meaning attempts at change are wasted. I disagree. Change—real change—happens only through conflict and disruption of the status quo, whether mild or intense, and as long as The Money is equated with The Answer, very little will really change. Accusations that funders are rolling out The Solution du jour are not always unfounded. To be sure, many of us in philanthropy have the freedom and the obligation to explore information on new and useful approaches, and bring them in when we believe they can address community needs. That’s an advantage of being in this position, if we pursue it. But that makes us bearers of information, not agents of change. That’s the work of our “customers.” We may be the architects, but they are the builders, and they know that what’s in the pretty picture doesn’t always work on the ground. (See the excellent book on this by Michael Pollan called A Place of My Own.)

So, how to change this? For my part, I try to mitigate the trappings and symbols of my role as much as possible. I don’t wear suits (symbols of power) when I don’t have to; I have the majority of my meetings in neighborhood coffee shops instead of in our 36th-floor, walnut-and-leather offices downtown (though the view of the lake is fabulous!); and I work pretty intensively with people bringing proposals to help shape and refine the ideas. It’s never just a “yes” or “no.” And yet despite this, the encounters are still uneasy. They know that what I say to my board about their proposal will significantly influence the decision. I know that, too. All I can do, ultimately, is pay attention to that, and acknowledge the imbalance of power as much as possible.

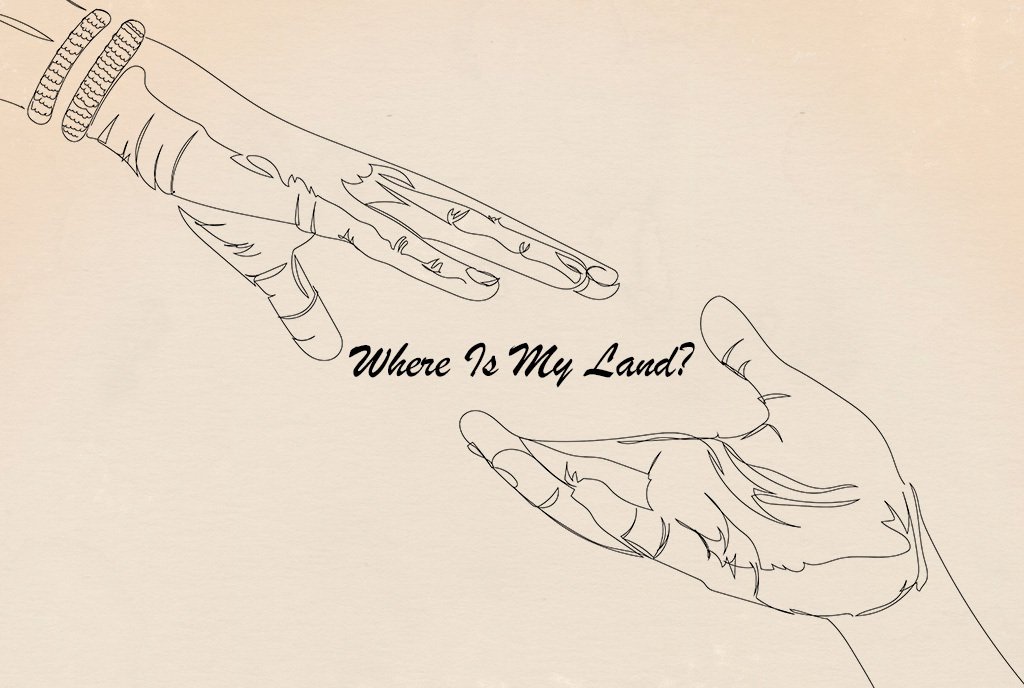

What they can do is be more assertive in relating their knowledge of how things work on the ground. Unfortunately, many believe that doing this will further jeopardize and already unbalanced interaction—piss me off, to put it bluntly—and damage their chances of getting a grant. As funding sources and levels are further squeezed, the competition for funds will further constrain their ability and willingness to be more open. Despite my best intentions, and their genuine desire to believe me, we will remain reluctant dancers in a rule-bound dance.

Paul T. Hogan is Vice President of the John R Oishei Foundation