November 16, 2018; Hyperallergic

Context is everything. That’s as true for the conversations about cultural property and repatriation as it is of the objects at the center of those conversations. This week, important conversations are taking place between representatives of the British Museum in London and residents of Easter Island, who have traveled to England to demand the return of one of their sacred objects.

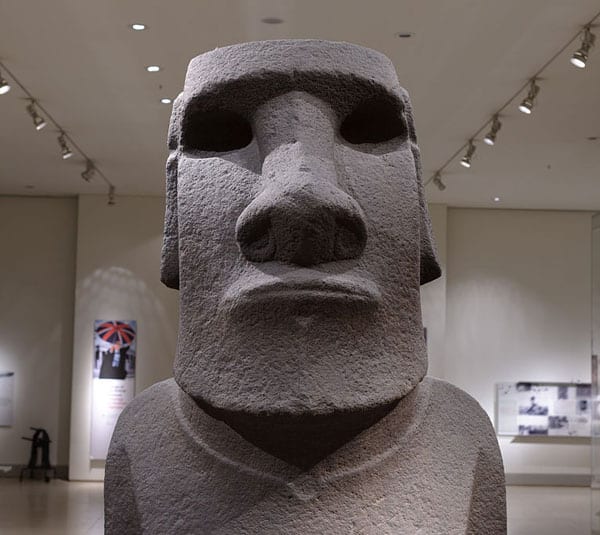

In 1868, a British naval captain named Richard Powell visited Easter Island and brought away a statue called Hoa Hakananai’a. Appropriately, the name translates to “the stolen friend.” Powell gave it to Queen Victoria, who gave it to the British Museum the following year. It has lived there since, and remains one of the museum’s most popular attractions.

Easter Island is known to its inhabitants as Rapa Nui, a name that also describes its indigenous people. It is the southeastern-most Polynesian island and one of the most remote inhabited islands in the world; the nearest mainland country is Chile, two thousand miles away. The story of its people is a familiar one: After migrating to the island nearly a millennium ago, the Rapa Nui population grew to several thousand people with unique cultural and religious practices. Europeans arrived in the 18th century and wreaked havoc on the locals through enslavement and disease, and by 1877, only 110 Rapa Nui remained. In 1888, Chile annexed the island. The indigenous population bounced back, but were not granted citizenship until 1966. Rapa Nui remains a Chilean special territory fighting for greater autonomy.

Chile has taken an active role in UNESCO’s restoration of Easter Island’s famous statues, known as moai. National assets minister Felipe Ward has traveled with the Rapa Nui delegation to Britain to participate in the talks about repatriation.

“The moai are our family, not just rocks,” Anakena Manutomatoma, a member of the Easter Island development commission, told the Guardian. The statues are religious icons representing ancestors and deities. The island’s authorities said, “It’s a unique piece, the only tangible link that accounts for two important stages in our ancestral history.” Hoa Hakananai’a is unique both because of the carvings on the back and because it is made from basalt; most moai are carved from tuff, a softer rock made of compressed ash. Local leaders also said the return of the statue would be “an important symbol in closing the sad chapter of violation of our rights by European navigators.”

Moira Simpson, a scholar of repatriation, writes, “For some communities, the repatriation of ceremonial materials from museums…has the capacity to contribute to indigenous health and well-being…Historical factors and their contemporary legacy have been identified by commissions of inquiry as primary causes of social ills and health problems” in other indigenous populations.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The narratives surrounding repatriation are informed by the colonial values and practices that still shape museum policy. For one thing, the idea that a sacred or a religious object “belongs” to a person or an institution is fairly Eurocentric. For another, museums often treat the objects like time capsules that offer a precious glimpse into dead or vanished cultures—even when living representatives of that culture are on the doorstep demanding recognition. Simpson writes, “Indigenous people frequently refer to the limitations of museum display as a means of expressing and preserving culture, emphasizing that culture is a living process that incorporates both continuity and change.”

The people of Rapa Nui are reviving their cultural practices, and local sculptor Benedicto Tuki has offered to carve a replica of Hoa Hakananai’a for the British Museum if they repatriate the original.

“Perhaps in the past we did not attach so much importance to Hoa Hakananai’a and his brothers, but nowadays people on the island are starting to realize just how much of our heritage there is around the world and starting to ask why our ancestors are in foreign museums,” Tuki told the BBC’s John Bartlett.

The Museum’s policy on repatriation “starts from a presumption of retention which can be outweighed in certain circumstances,” but claims that trustees’ ultimate duty is protection of the collection. So far, they have agreed to a second meeting on Rapa Nui, but nothing more.

Why does the museum’s policy start from a presumption of retention? It prioritizes the learning and experiences of museum visitors in colonizer countries over the healing and cultural practices of the communities from which objects were taken. The guidelines from the Museums Association recommend taking into account “the interests of actual and cultural descendants,” but also “the law” and “current thinking”—whose thinking is not specified, but we can guess.

In the case of Hoa Hakananai’a, exchanging the statue for a replica would arguably provide a greater educational experience for museum visitors, one that includes a discussion of museum ethics, preservation of living cultures, and some painfully honest history. Insisting on retaining the original would be an imperial move by the museum, a reiterated claim to define spirituality, ownership, and authenticity for a colonized people.

Chile hasn’t escaped scrutiny just because it’s aiding the delegation. Tuki added, “In order for Chile to show that it is serious about supporting our cause, we need to have the moai on the Chilean mainland returned to the island.”—Erin Rubin