July 16, 2019; New York Times

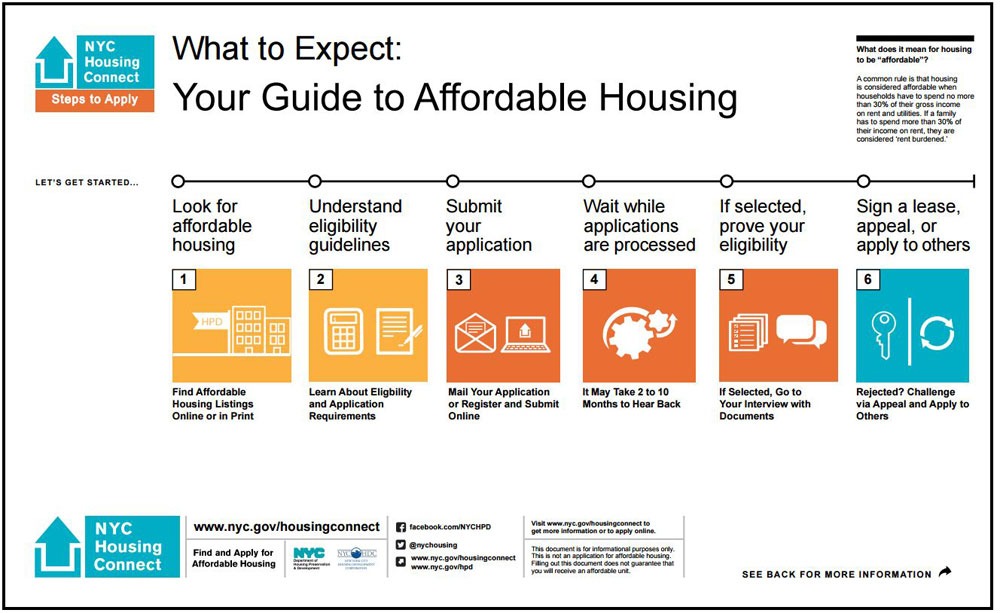

As NPQ has reported in the past, the affordable housing crisis is “a byproduct of our nation’s second Gilded Age of mounting income and wealth inequality.” Given the number of stakeholders, creating public policy in this context can be complicated, and care must be taken to ensure that policies do not increase race and class segregation. This, unfortunately, is not the case for the city of New York. In fact, an expert found that New York City housing policies actually deepen segregation in some communities.

A recent report conducted by a sociology professor at Queens College, Andrew Beveridge, filed in US District Court in the Southern District of New York, contends that New York’s policy of giving local residents priority in housing lotteries ends up keeping white neighborhoods white and black neighborhoods black. Beveridge’s study, notes J. David Goodman of the New York Times, was conducted “on behalf of plaintiffs in a lawsuit brought by three Black women from Brooklyn and Queens who said they were not given a fair chance to win affordable apartments in city-managed lotteries.”

The policy allows local residents preferential access to 50 percent of affordable apartments, leaving the other half open to people who want to move into the neighborhoods. However, by the time other applicants want to move into the area, many of the apartments they would qualify for have already been taken. This cycle allows the majority group in that area to have an advantage over other racial groups. As Beveridge states in his report, “The result of the operation of the community preference policy is a pattern that perpetuates segregation more (and allows integration less) than what would exist without the policy.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Vicki Been, who formerly ran much of the city’s affordable housing program and who recently became deputy mayor of housing, has stated that this policy was put into place to “address the fear of displacement in communities.” In other words, it’s to keep people with low incomes from communities of color from being dispersed when the gentrification monster comes knocking. The city also commissioned a counter-report of its own, authored by statistician Bernard Siskin, which claims the policy of community preference has no disparate racial impact citywide because, as Goodman puts it, “every racial group is helped somewhere.”

Still, Been’s defense of city policy is less than convincing. “Segregation is a question of choice, and people who chose to live in a neighborhood, we believe, should be able to choose to stay in a neighborhood,” certainly makes it sound like Beveridge has a point. Goodman adds that “Been admitted in a deposition that she would not choose the policy if her only goal was to reduce segregation.”

Clearly, a holistic approach to counteract the systemic racism in New York City neighborhood housing is needed. In a recent article, NPQ provided steps to a more multifaceted approach to the affordable housing crisis. One of the most important is to create a space for current residents to provide feedback and weigh in. If the city had checked in with current residents who were impacted by the policy, they could have learned of the outcomes sooner.

As we create policies and procedures and attempt to provide services to communities, we must understand who our efforts are meant to help. We must express in clear, non-coded ways what issues we face and what outcomes we desire. In this way, we can tackle problems head-on and fix them.—Diandria Barber