Editors’ note: This article is from NPQ‘s winter 2022 issue, “New Narratives for Health” and was adapted from The Four Pivots: Reimagining Justice, Reimagining Ourselves by Shawn A. Ginwright (North Atlantic Books, 2022).

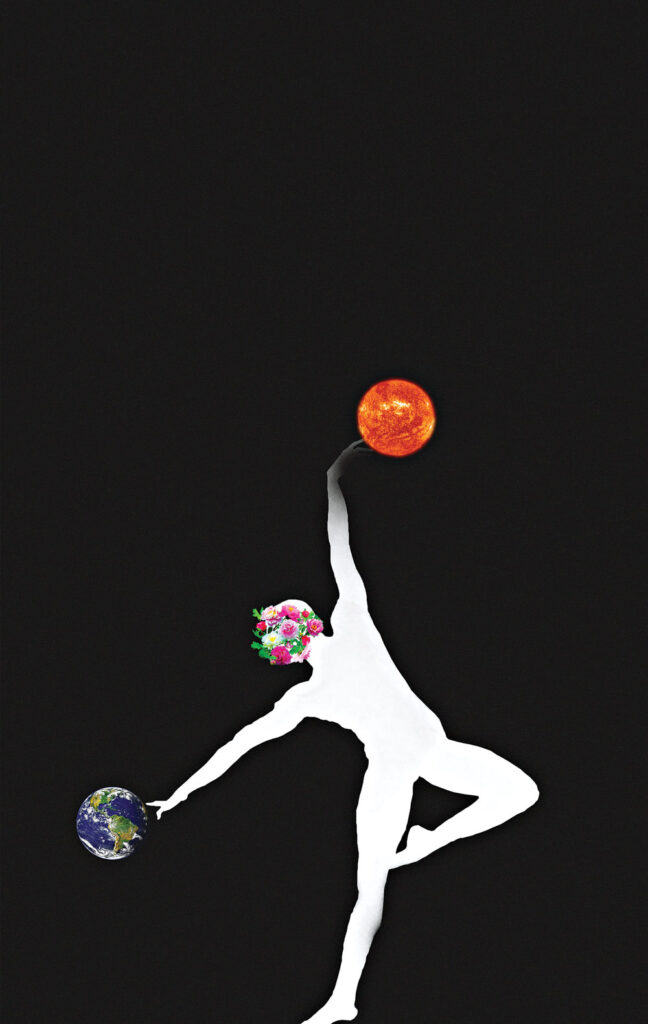

Click here to download this article as it appears in the magazine, with accompanying artwork.

Lately, I’ve been having trouble sleeping. I thought my sleepless nights would pass and that in time I would return to waking up feeling rested, revived, and refreshed. But that hasn’t happened. My sleepless nights appear to be here to stay.

I suspect that some of my sleep habits come from my father. I can’t recall a time in my life seeing my father sleep. Growing up, I never saw him in bed, because he worked the swing shift (4:00 p.m. to 12:00 a.m.). By the time I went to sleep at night, he was at work, and when I woke up in the morning, he would already be up fixing things around the house. He didn’t believe much in rest; sleeping for him was a “waste of good time.” My father probably had problems sleeping because he worked so much, the night shift disturbed his circadian rhythm, and he was more concerned with feeding us than with the quality of his sleep.1

Many of us who work tirelessly to address social problems and improve the quality of life for communities do so without much consideration of the toll our work takes on our ability to rest. Whether you are a teacher, a community organizer, or a social justice activist, you are probably habituated to the stress, anxiety, and lack of rest your work creates. Creating and sustaining social justice movements and/or work in the field of care requires intense dedication and commitment that can cause burnout. Activist Yashna Maya Padamsee describes it like this: “We put our bodies on the line every day—because we care so deeply about our work— hunger strikes, long marches, long days at the computer or long days organizing on a street corner or a public bus or a congregation. Skip a meal, keep working. Don’t sleep, keep working. Our communities are still suffering, so I must keep going.”2

Leaders tend to devalue rest—which is dangerous for our movements, communities, and selves. Not only do we often devalue rest, we may also view rest as a sign of weakness. This message is everywhere, and every day we unconsciously take small bites of this poisonous apple. Take, for instance, the popular lyrics in “Ella’s Song,” by Sweet Honey in the Rock: “We who believe in freedom cannot rest. We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes.” On the surface, the meaning is that we must remain committed and dedicated to our tireless work for freedom; but on a deeper level, it reinforces the idea that we can and should sacrifice rest in the name of justice.

Rest is not just the ability to get a good night’s sleep. It’s also the ability to not constantly worry—to have sustained peace of mind. A sustained peace of mind comes from the stability of a good job, knowing that your children are safe, knowing that you are not going to lose your home. These securities are not always available if you’re poor, immigrant, Indigenous, or Black. The stresses that come from constant worry about basic life necessities, concern over personal safety, and persistent cuts from racial microaggressions all add up and create yet another form of inequality we rarely talk about and only vaguely understand: rest inequality.3

Rest inequality refers to the gap in the quality, duration, and amount of rest people get depending on their status in Western culture.4 This gap is created and maintained by structural inequality; it is not the result of personal choice, as some would have you believe. Researchers have found that the duration, quality, and frequency of rest in general and sleep in particular are shaped by income level, housing conditions, employment status, type of work, and race. Dr. Dayna Johnson, public health researcher at Emory University, has extensively studied sleep disparities and has shown that “racial/ethnic minorities are more likely to experience, for instance, shorter sleep durations, less deep sleep, inconsistent sleep timing, and lower sleep continuity in comparison to Whites.”5 Sleep is one of the most important aspects of rest, and more and more people are paying attention to the critical role that good sleep plays in all levels of physical and mental health from birth through old age, and its connection to learning, work, sound decision making, and so much more.

Rest Is An Act of Freedom

Rest is not just sleep or dormancy; it is an act of freedom—a middle finger to oppression that tells us to work tirelessly for the pleasure of capitalism. The idea that rest is a weakness or luxury has a long history in America, and it is still deeply rooted in white supremacist Western culture. The uniquely American concept of “rugged individualism,”6 for example, which emphasizes self-determination—combined with the Protestant work ethic that promotes the idea that hard work makes people more likely to go to heaven—helped to lay the ideological groundwork in the United States that devalued rest.7

People of color, in the minds of white America, have primarily been seen as labor to exploit. Rest, for folks of color in white supremacist culture, has to be earned first by demonstrating unquestioned loyalty and dedication to sweat and toil.

Indeed, this idea that if you work hard, capitalism will reward your efforts is deeply rooted in the American belief system and was fueled by the Industrial Revolution. And if America was built by the Industrial Revolution, then the Industrial Revolution was built on African slave labor. This meant that enslaved Africans were primarily, and singularly, seen as labor—the magic lever in the industrial capitalist machine that could produce the raw materials for the new industrial economy. Black bodies were and continue to be viewed through that lens. And despite four hundred years of free labor in sugarcane fields in the Caribbean and cotton or tobacco plantations in the South, the ridiculous term lazy is still hurled at Black people and other communities of color. The term is used to justify the sanctity of capitalism, and it serves as evidence as to why Black folks as a whole haven’t yet benefited from capitalism—they apparently haven’t worked hard enough.

African slave labor is just one of many examples of how the idea of rest as weakness permeates our society. It also applies to Mexican farmworkers in the Central Valley of California and Chinese workers whose labor created the transcontinental rail system. People of color, in the minds of white America, have primarily been seen as labor to exploit. Rest, for folks of color in white supremacist culture, has to be earned first by demonstrating unquestioned loyalty and dedication to sweat and toil; only then, after you have worked to maximum output, is rest considered permissible. But even then, rest is viewed as a way to “recharge” just in order to plug right back into the frenzy and hustle of work. Rest and leisure are reserved for the white folks, who supposedly earned the luxury. Rest and race are intertwined, and it all boils down to who has the right to rest and under what conditions rest and leisure should be granted.

Rest Is An Act of Core Health

The role that sleep plays in learning, mental health, physical health, stress reduction, and so much more is gaining attention. A review of one hundred studies exploring the influence of sleep on health outcomes found that poor sleep often leads to a host of other issues, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, decreased cognitive performance, and impaired mental health.8 There is consensus among researchers that a significant “sleep disparity” exists in America that is clearly based in race.9

In the June 2015 edition of the journal Sleep, researchers published a study on the sleep quality of Black, white, Chinese, and Latinx adults in six cities across the United States.10 Participants in the study, which involved over six thousand people in order to better understand the impact of geography and race on sleep and sleep’s impact on health outcomes, wore Fitbit-like bracelets that tracked the duration, disruptions, and overall quality and quantity of their sleep. Researchers found that African Americans were getting the least amount of sleep among the racial groups, and that on average, the sleep quality of whites was better than that of the other ethnic groups.

Rest inequality is not only about the racial and ethnic gaps in the quality and duration of our sleep; it also involves gaps in how we spend our leisure time, how we play, the quality of our recreation, and the amount of time we spend in pleasurable activities. For example, researchers have found that when compared to whites, racial and ethnic minority groups are less likely to engage in leisurely activities—such as taking a walk, dancing, gardening, sewing, or dedicated physical exercise such as jogging or yoga.11

Some of us refuse to believe this is a problem, putting the effects of sleep and rest inequality far below other inequalities that make up the injustices in our society. But sleep and rest inequality in many ways forces us to see the connections among all forms of inequality. As I’ve noted, rest inequality is tied to economic inequality, because quality rest is the result of peace of mind, a secure job, safe neighborhoods, effective medical care, and regular time spent with loved ones. Indeed, sleep and rest inequality permeates all aspects of our lives and requires that we rethink, reimagine, and readjust our connections to how we work, live, and play. Ask yourself: What is the quality of my sleep? How much rest do I get every day? How do I spend my leisure time? How much sleep and rest do I lose due to stress?

Another question to ask is whether your work is governed by a “grind” culture. Heather Archer, author of The Grind Culture Detox: Heal Yourself from the Poisonous Intersection of Racism, Capitalism, and the Need to Produce, shows us that grind culture permeates how we relate to one another and places a premium on getting the job done, even if it means working through the night, missing your child’s soccer game, or postponing a night out with your friends, and so on.12

As a professor, I have supported numerous students with breaking their addiction to grind culture. I recall one student who, on top of her studies, was building a nonprofit organization in service to underperforming schools. She was also involved in organizing parents to reject the district’s proposal to close several schools in her city. All of this required an enormous amount of work. She had asked me for several extensions for her papers because her plate was overfull. When we met she looked tired—not tired like she had had a long day but exhausted tired, like she was holding on to a sack of bricks that was pulling her down to the bottom of the sea. She explained to me that on top of all that she was doing, her mother was sick, and she was the primary caregiver. Despite this, she believed that she had to grind it out for the community. I explained to her, as I do to all my students, that nothing is more important than one’s health and well-being. I suggested that she take some time off and get someone else to take over some of her activities. We talked for over an hour, and she explained to me that she just couldn’t imagine what people would think of her if she stepped aside; she didn’t want to let the community down. About a week or two later, I noticed that she hadn’t returned to class, and I learned that she had been hospitalized after passing out from exhaustion. The following semester, she came to see me, and we talked about what had happened. She looked much better, her eyes were bright and alive, and I could tell she had turned a corner. She explained to me that being hospitalized was one of the best things that could have happened to her, because she had been forced to rest. She had also taken the time to reprioritize and was incorporating regular rest and leisure into her life.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

We . . . have to build practices in which we prioritize rest and play— not as acts of self-indulgence but rather as critical components of our journey toward justice. This is why we have to understand rest as a right—not a privilege for those who can get and enjoy it.

Grind culture is dangerous, and we have to learn how to rethink our deeply ingrained fatalistic ideas about how to engage in community change. We know from research that rest and leisure have numerous physiological benefits ranging from reducing stress, illness, and serious/chronic diseases to supporting creativity and boosting the focus and concentration required for deep listening to others—all of which are essential to our work for social change.13

We also have to build practices in which we prioritize rest and play—not as acts of self-indulgence but rather as critical components of our journey toward justice. This is why we have to understand rest as a right—not a privilege for those who can get and enjoy it. The term self-care, for example, has become popular among social justice advocates as a way to convey the need to take care of ourselves. But the term conveys the idea that caring for oneself is a privilege you can access if you have the time and money. Calling rest and other healthy behaviors “self-care” has resulted in separating them from health and from health for all—because when we think about care in this way, it’s akin to saying, “My well-being isn’t dependent upon yours.” It reinforces the idea that we are separate, disconnected, and independent from one another. We learned from the COVID-19 pandemic that our well-being is deeply interconnected, and that if one of us is sick, we are all at risk. So, I prefer the term collective care—not to discount the value of your massage, warm bath, or quiet walk in the park but rather to cultivate an awareness that caring for ourselves is deeply connected to, indeed, indivisible from, the well-being and concern of others. This is fundamentally what our movements for justice are based on, and there are no movements without shared concern and care for others.

Rest Is An Act of Justice

When I was growing up, my father would explain to me that crops that are grown in the same soil over time actually harm the soil. This is because overproduction of crops in the same soil drains the soil of key nutrients necessary for growth and flourishing. The soil is the most important factor in growing healthy plants, and without good soil, nothing you do really matters. Pops explained that wise farmers let the soil rest for a season, knowing that resting the soil would ultimately produce better crops. Resting the soil regenerates nutrients, replenishes important minerals, and restores soil quality.

We should learn from these wise farmers and prioritize the need to replenish. We all have the right to restore ourselves. Rest is an act of justice. When we rest, we call attention to the oppressive ways that capitalist culture devalues replenishment and tells us that rest is reserved for those who have “earned” it. We need to democratize rest and make it more available to those who need it most. This means rethinking our work hours and reimagining how and where we work.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced us to reconsider how we work, because so many of us had to work from home. Companies had to create new ways of working for their employees, and this opened a door to re-visioning work culture. For example, what if we reduced the forty-hour work week to thirty hours, or adopted a Monday through Thursday standard work week? Some US companies have already started exploring alternative ways to promote employee well-being. For example, the right to work remotely and unlimited paid time off have become popular among some industries.14

In the meantime, how can we exercise our right to rest?

First, ask yourself, “What is my relationship to rest?” This question will help you to identify the messages we hold about rest and identify the consequences these messages have for you. Do you think that rest is weakness, or that rest is not important? Where did you learn those messages? (Ask yourself the same questions in terms of your sleep.) These are just a few questions that can help you to identify your relationship with rest.

Take some time to write down your responses. This is an important step, because by exploring these questions, you will identify the structural impediments and opportunities that shape your rest habits.

Then, take an inventory of your sleep and rest habits. Do you keep your phone charging in your bedroom? If your cellphone is charging up near your bed, it may well be draining you of your rest, because your brain will be attuned to that next beep or buzz of a notification—a pernicious result of capitalist culture. Take some time to make a list of how you sleep and rest over the period of a week. Begin with how you felt waking up in the morning, and list what you did during the day that you considered restful or not. Did you exercise or go to the farmers market? Did you respond to emails and crank out the report that you’ve been avoiding? Just list a few activities that either enhanced or impaired your rest and sleep during the week. Once you have this list, you can ascertain if you are getting enough rest, what your favorite ways to rest are, what gets in the way of rest, and what supports your rest. Then, explore ways to reduce or eliminate those activities that impaired your rest, and try to add things that enhance your rest and sleep quality. By doing this, you create your own rest and sleep plan and reprioritize ways to enhance the frequency, quality, and duration of your rest and sleep.

Finally, form a “radical rest” group among your colleagues at work or friends and family. A radical rest group is just a small group of five to ten people who are curious about the significance of rest in their efforts for social change. This is not a support group for rest—a radical rest group works together on how to build systems of support for rest for everyone. Rest inequality is not a personal choice but rather a result of structural and cultural inequality. A radical rest group comes together to reimagine how to democratize rest in our society, and asks questions like: How can we reshape policies in workplace settings that give employees more time to rest? How might we reimagine the work week in order to provide more time to spend with friends and family? How might we cultivate a culture where rest is not viewed as a weakness but rather a strength, and is understood as a basic human right?

***

Rest is like food—and just as we must pay attention to how we are cultivating and replenishing our soil and ensuring that all have access to healthy and nourishing foods, we must also pay attention to our physical and spiritual replenishment.

Everyone has the right to rest, and it is an important step in the pivot from our addiction to frenzy to an embrace of flow. Frenzy is a state of desperate, unending, unfocused effort that consistently fails to produce desired results. It is the dreaded treadmill to nowhere, and its consequence is a persistent feeling of being overwhelmed. Flow, on the other hand, is a state of tranquil, consistent, focused activity that consistently produces desired results. It is a state of awareness that is free of judgment, doubt, fear, and confusion, and is guided by a sense of effortless certainty.

Rest is like food—and just as we must pay attention to how we are cultivating and replenishing our soil and ensuring that all have access to healthy and nourishing foods, we must also pay attention to our physical and spiritual replenishment. Like the wise farmers who allow their land to rest, replenishing ourselves is the only real way to make the deep change we need in our world.

Notes

- Research on sleep disorders has shown that night shift workers are more likely to experience disruptions in circadian sleep See Suzanne Ftouni et al., “Ocular Measures of Sleepiness Are Increased in Night Shift Workers Undergoing a Simulated Night Shift Near the Peak Time of the 6-Sulfatoxymelatonin Rhythm,” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 11, no. 10 (October 2015): 1131–41.

- Yashna Maya Padamsee, “Communities of Care, Organizations for Liberation,” naya new. (blog), June 19, 2011, nayamaya.wordpress.com/.

- Dayna Johnson et al., “Understanding the role of structural racism in sleep disparities: a call to action and methodological considerations,” Sleep 45, no. 10 (October 2022).

- Lauren Hale, Wendy Troxel, and Daniel Buysse, “Sleep Health: An Opportunity for Public Health to Address Health Equity,” Annual Review of Public Health 41, no. 1 (April 2020): 81–99.

- Dayna Johnson et al., “Are sleep patterns influenced by race/ethnicity—a marker of relative advantage or disadvantage? Evidence to date,” Nature and Science of Sleep 11 (July 2019): 79–95.

- Samuel Bazzi, Martin Fiszbein, and Mesay Gebresilasse, “Frontier Culture: The Roots and Persistence of ‘Rugged Individualism’ in the United States,” Econometrica 88, no. 6 (November 2020): 2329–68.

- Charles Ward, “Protestant work ethic that took root in faith is now ingrained in our culture,” Chron, September 1, 2007, chron.com/life/houston-belief/article/Protestant-work-ethic-that-took-root-in-faith-is-1834963.php.

- Vijay Kumar Chattu et , “The Global Problem of Insufficient Sleep and Its Serious Public Health Implications,” Healthcare (Basel) 7, no. 1 (2019), doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7010001.

- Soojung Ahn et , “A scoping review of racial/ethnic disparities in sleep,” Sleep Medicine 81 (May 2021): 169–79.

- Xiaoli Chen et , “Supplemental Material,” Tables S1–S4, 888A–888C, Figures S1, S2, 888D, in “Racial/ Ethnic Differences in Sleep Disturbances: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA),” Sleep 38, no. 6 (June 2015): 877–88.

- Maria Allison, “Leisure, Diversity and Social Justice,” Journal of Leisure Research 32, no. 1 (2000): 2–6.

- Heather Archer, The Grind Culture Detox: Heal Yourself from the Poisonous Intersection of Racism, Capitalism, and the Need to Produce (San Antonio, TX: Hierophant Publishing, 2022).

- Kannan Ramar et , “Sleep is essential to health: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement,” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 17, no. 10 (October 2021): 2115–19.

- Daniel Hamermesh and Jeff Biddle, “Days of Work over a Half Century: The Rise of the Four-day Week,” Working Paper 30106, National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2022; and Madeline Miles, “Is unlimited PTO right for your company? Everything you need to know,” BetterUp (blog), October 7, 2022, betterup.com/blog/unlimited-pto.