Let Us Now Praise Famous Men by James Agee is a book perhaps best read aloud. At the least, it’s a book the reader is advised to approach with respect, like being quiet as a thunderstorm approaches. The vivid power of this strange classic made this landmark piece of social documentary one of the most influential books of the twentieth century.

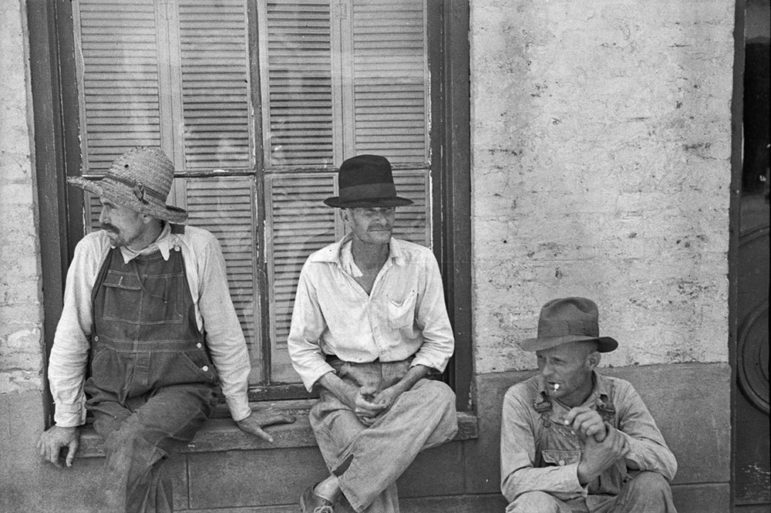

The story of how the book came about is as ironic as the book’s title. In the summer of 1936, as part of Fortune magazine’s “Life and Circumstances” series, Agee and photographer Walker Evans were given a month-long assignment to document the wretched lives of white sharecroppers in the deep South during the worst of the Great Depression. They drove to rural Alabama, as distant culturally as one could get from the magazine’s headquarters in the then-new Chrysler Building. They explored the lives of two tenant farmers and a sharecropper, whom Agee called the Rickettses, the Woods, and the Gudgers. Agee stayed with one of the families, while Evans preferred a hotel in a nearby town. Agee turned in about 30,000 words. (Here are the images Evans captured.)

Fortune never published the article, but the work was published as a book in 1941, the final year of the New Deal. About 600 copies of the book were sold before it disappeared from shelves. This book that nevertheless shattered journalistic and literary conventions was reissued in the 1960s, where it found an audience. In his review, Lionel Trilling wrote that the book is “the most realistic and the most important moral effort of our American generation.” Fifty years after Agee’s death, the original 30,000-word report for Fortune was found and published as the short book, “Cotton Tenants: Three Families.”

Christopher Knapp, writing for The Los Angeles Review of Books, asks how Agee would undertake the same kind of documentary work in covering the current presidential campaign.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

When undertaken in good faith, is still the best tool we have for listening to each other’s choirs. Agee wasn’t the first immersive journalist, but he was one of the first to give so much thought to what that good faith would look like. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men has been a touchstone in countless treatises on journalistic ethics, but of course it is its own treatise on journalistic ethics—searching and flawed, but indispensable.

The book’s title is taken from a quotation from one of the Apocrypha of the Old Testament: Let us now praise famous men and our fathers that begat us. The irony of the book’s title is harsh. The people Agee describes are the most rejected and hidden. Uncompromising in his pursuit of emotional truth, Agee was troubling for Fortune and for his unsuspecting readers. And that is what Knapp is saying we need more of today.

Knapp shares the content of the letter Agee wrote to his former grade school teacher to discuss the Fortune assignment. Agee assumed the magazine’s expectation was for him to write “a brand of muckraking—a self-congratulatory aestheticization of poverty that disguised itself as a call for reform.” Agee dismissed this as “the pinnacle of Northern arrogance.” Instead, Agee wrote, “Feel a terrific personal responsibility toward story, considerable doubts of my ability to bring it off; considerable more of Fortune’s ultimate willingness to use it as it seems (in theory) to me.” Agee brought it off and Fortune predictably refused to publish it.

Knapp reflects on how challenging it is “for us to understand each other—how successfully we’ve divided ourselves into choirs to be preached to. Our earnest attempt to remedy for this hopeless state of affairs is the convention of sending investigators into each other’s midst.” But Knapp wonders if there are any journalists today of Agee’s moral fiber willing and able to do the necessary work.—James Schaffer