August 21, 2019; Chronicle of Higher Education

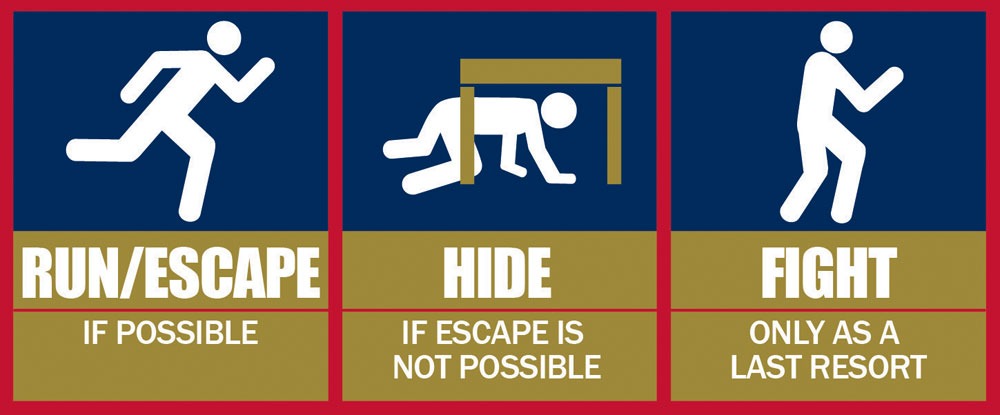

It’s the first day of school. You are a first-year college student, and you walk into your lecture hall to be educated in the basics of “run, hide, fight,” the mantra of active-shooter response training. Or perhaps you are a parent, greeting your child with the classic, “So how was your day?”—only to be told your seven-year-old learned to barricade the door to her classroom and find a hiding place.

This, it seems, is the new normal of efforts to fight back against school shootings. The questions in all this are, will this be effective? Have we put the burden of protection on the victims? And are there repercussions just to subjecting students, no matter their age, to this kind of training?

Across the country, colleges and universities are responding to campus shootings with mandatory trainings of faculty who, in turn, take class time to inform and share their new-gained expertise with students. Campus classrooms are being equipped with locks that offer some comfort and protection to those inside, unless a shooter is already among them. Then other scenarios must come into play. Professors who were looking forward to delving into the intricacies of sonnets or physics or chemistry are now becoming experts on safety and evacuation.

At the elementary school level, one of the processes for active shooter response taught to faculty and used with students is ALICE:

A – Alert: This is your first notification of danger. It is recognizing the signs of danger and receiving information about danger from others.

L – Lockdown: If evacuation is not a safe option, you would barricade entry points into your room to create a semi-secure starting point.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

I – Inform: If it is safe to do so, communicate real-time information on the location of the violent critical incident. Use clear and direct language using any communication means possible.

C – Counter: As a last resort, create noise, movement, distance, and distraction with the intent of reducing an individual’s ability to cause harm.

E – Evacuate: When safe to do so, run from danger using non-traditional exits if necessary. Rally points should be predetermined.

It seems simple. But in an emergency, will these steps work? And how much practice will be needed, and will that generate concern and trauma in young children? These are the unknowns.

Just as we practice fire drills and tornado drills, schools now practice active shooter drills. But the impact of these drills may not be the same. In all of this preparation for the worst, those looking at what is best practice have been concerned that our efforts to prepare are also potential triggers for mental health incidents before a trauma as well as after one. When police wearing guns and carrying rifles show up because there was a false alarm (which happened twice on two campuses as they were practicing), the ordeal for students and faculty is real. So were the apologies, but that may not make up for the residual trauma. As Melissa Reeves, associate professor of psychology at Winthrop University, who helped compile the National Association of School Psychologist’s best-practice guide for dealing with active shooters, states, “We don’t light a fire in the hallway to practice fire drills. We do not have to do highly sensorial active-shooter drills to be ready for active shooters.”

As we prepare for future mass shootings, we congratulate ourselves for our efforts in training those who work at schools and on college campuses to protect children from harm and trauma. Though there’s limited support saying that these efforts and techniques are effective, we undertake them because they seem to be all we have to offer. Something seems to be missing. Why do our leaders not give equal time and effort to gun safety and regulation?—Carole Levine