May 4, 2019, Concord Monitor

As we have reported, citizen scientists—the volunteers who unfailingly show up to gather information and learn at the same time—can contribute to significant studies. These days, in New Hampshire, the citizen scientists are collecting every tick they find on their skin and clothing and mailing them away to a lab.

Of course, since they are gathering data, they also record the day, time, and place they noticed the tick. Because of their diligence, they have discovered that tick bites are a danger even in winter, and they found New Hampshire’s initial case of a new tick-borne disease.

Kaitlyn Morse, a Plymouth State University scientist who had been working on vaccines for tickborne diseases, founded the nonprofit BeBop Labs and created the tick collection program. (The organization has only had its IRS determination letter for a few weeks.) Dr. Morse noticed there was little tick data that included central and northern New Hampshire. Citizen scientists rose to the challenge, and in 2018, more than 1,650 ticks were sent in from New Hampshire, plus a few from surrounding states.

“Neighboring states have more data and information than New Hampshire, they have programs in place. New Hampshire is often following on their coattails,” Dr. Morse says. “This could make New Hampshire a leader in tick surveillance—using hands-on science, having every individual be proactive in answering their own questions.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

BeBop, named for Morse’s pet chocolate Labrador retriever, is focusing on outreach and education along with research on the diseases. They want to teach their community how to dress and behave outdoors to dodge ticks. The 2018 collection showed that between 25 and 50 percent of ticks carry at least one disease that can be passed to humans.

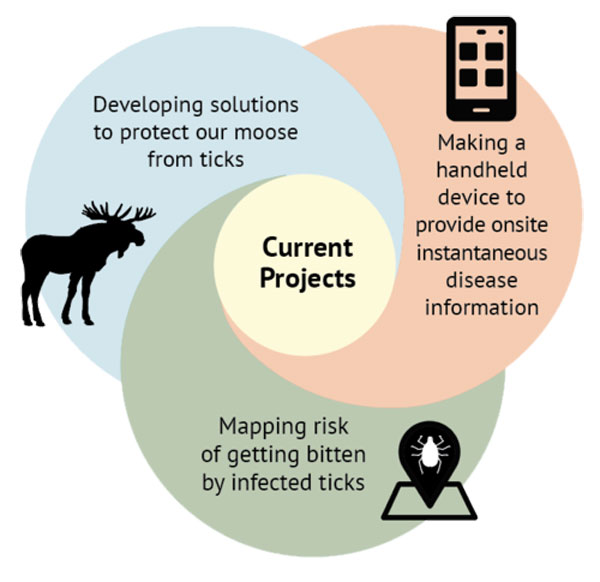

The data provided by the volunteers also comes back around to help them. University of Massachusetts–Amherst’s Laboratory of Medical Zoology and a company called Ticknology have included their public data with the volunteers who send in their ticks. BeBop Labs hopes their sociological research and GIS [geographic information systems] mapping will add to their educational outreach.

Of course, one year of data does not signify a trend. Dr. Morse would like to see three years of data before making real projections. “Some of the counties are not well represented,” she says, “but it is, I think, an indication of what’s out there.” Fortunately for BeBop Labs, citizen scientists are just getting started, earning their keep with their consistency and good record-keeping.

This is an important season for deer and dog ticks, with newborn ticks coming out. None of the dog ticks that were tested carried Lyme or other disease, but the scientists will be collecting any tick they see. Fortunately, spring tick cycle will give the volunteers more bugs to bag up and bring to the post office.

With Lyme disease and other pathogens like miyamatoi and babesia found in the ticks, the work of the citizen scientists is critical both to research and public health.—Marian Conway