December 7, 2017; Hyperallergic

The complex patterns of political dissidence woven by protest movements in 2016 look set to intensify in 2017. In addition to the well-known ongoing internationalized protests of Oromo, “(Rhodes and Fees) Must Fall,” “Bring Back Our Girls,” and “Black Lives Matter,” already in January 2017 there have been student protests in Nigeria and a mass women’s march scheduled for the inauguration of U.S. president-elect Donald Trump on January 20th, which itself will be boycotted by at least 50 Democrat representatives. This seems like an opportune time to “reconsider the aesthetics of protest,” in America as elsewhere.

In a thoughtful December 2016 piece on the issue, Jeremy Bendik-Keymer suggests that the “overgeneralizations,” “insults,” random untargeted messages, and sky-shouting typically associated with many protests need to be reconsidered and thought through more carefully. There’s some wisdom here, especially with regard to those protests that seek primarily to change policy. However, there is a symbolism and significance to “uncoordinated” protests that’s not necessarily measurable in terms of policy changes or influence. Further, “shouting” is only one aspect of how protests are done. Silence, written petitions, and the willful absence of the physical body are also frequently used.

For one thing, spontaneity is at the core of many protests. People partake in them as an in-the-moment gut reaction—an outcry—against an outrage that resonates on a deep emotional level. In a recent CNN interview, one participant in the Charlotte protests against the police killing of Keith Lamont Scott said, “Honestly, neither of us knew what to expect. We just kind of wanted to be there and take part in a huge moment for our city and community.” It is an admitted risk with such impulsive action that it can easily turn violent, thus overshadowing worthy motives. But, this does not mitigate their intrinsic value of forcefully registering public discontent and disagreement. The power of rage is not easily dismissed or forgotten.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Decorous democratic discourse sounds great on paper. But contexts differ. It is easier to get close to and engage with leaders in some parts of the world than others, and many protests erupt for the very reason that leaders are just not accessible or that they pay lip service to considering change initiatives that do not emanate from government or other approved circles. Again, discourse is unlikely to work where positions and ideologies are so hardened and polarized that sitting down together cannot yield much good. Cases in point include the violent government crackdowns on protests in 2016 in Turkey, East Africa (Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia), and Myanmar.

It may not be fair to measure the potency and impact of protest aesthetics simply at face value, as the fact of their existence can have far-reaching, unforeseeable effects. Apart from voicing the existence of alternative ways of looking at things and of thinking about them, protests can enable social movements that can take up social and political issues more concretely and coherently. Also, it might well be that, without publicly admitting it, the fact of protests compels political leaders to think and act differently, though sadly there is not enough empirical evidence on how this works.

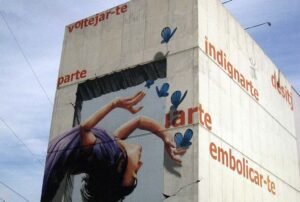

From these perspectives, “shouting at the sky” cannot be entirely futile. If the sky does not hear, the media and communities do. If leaders will not listen, they cannot easily erase the memory of protest imagery, which can be more powerful than words. Activists everywhere should by all means be more creative and strategic in their contentions in 2017, but they ought to be wary of doing so at the expense of the passion that fuels the most resilient protests.—Titilope Ajayi