“The philanthropic sector’s growing urgency to tackle inequities…offers strong motivation to take stock,” notes the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) in its new publication, “Power Moves: Your essential philanthropy assessment guide for equity and justice.” There are, of course, many positive examples of philanthropic action to address inequality. NCRP highlights a few of these, including:

- In Washington DC, the Hill-Snowdon Foundation “makes grants to organizations that use multi-generational approaches to address issues facing low-income youth of color and other marginalized youth, and multi-issue organizing that promotes family-supporting and community-strengthening jobs.” This includes creating both a fund and funder’s network to support Black-led organizing.

- In California, the California Civic Participation Funders has brought together foundations and grantees in a common network which, since 2012, has led to $4 million in funding that has helped strengthen local organizations and networks “to mobilize and engage underrepresented voters more effectively” in four Southern California counties.

- In Pennsylvania, in January of this year, the Pittsburgh Community Foundation, for the first time in its history, filed an amicus brief in a state supreme court case that ended up throwing out the state’s congressional district map and instating a new one that allows for more competitive elections.

The examples are inspiring, but they are also far less common than they should be. “Power Moves” aims to help change that by providing a toolkit that can help guide foundations through a process of self-assessment, planning, and action. Additional support materials are available online. Developed by a team led by Lisa Ranghelli and Jennifer Choi, the toolkit is predicated on the idea that “taking time out for self-assessment and learning is an important part of the organizational cycle of planning, action, and reflection.”

The toolkit is also grounded in the notion that seeking to achieve equity without addressing power and privilege directly is a fool’s errand, and the failure of some in philanthropy (and nonprofits too) to understand this can be dangerous. In their report, Ranghelli and Choi observe that because “power is not often discussed openly and directly, it tends to grow in unintentional ways that mirror and exacerbate dominant power structures.”

The toolkit builds on at least a decade of work by NCRP on these issues, and in particular its Philamplify project, which assesses “the effectiveness of foundations by interviewing and surveying grantees and stakeholders and examining documents,” as NPQ once described it. Over the years, Philamplify has provided equity assessments of a number of leading foundations and the lessons learned over the years have helped inform NCRP’s latest work.

One feature that is notable about the toolkit is that NCRP decided to focus not on philanthropy as a whole, but rather on those foundations which have already signed on to an equity agenda. In other words, the toolkit is designed to be used by foundations that have made a commitment to targeting grants to under-resourced communities and that have already made explicit commitments to promoting community engagement, diversity, equity, and inclusion.

The toolkit authors have gone so far as to include a “readiness assessment” checklist. And, if your foundation is not ready? In that case, the authors advise focusing on education and training of staff and trustees first. After that, maybe talk to “some of the funders highlighted in this toolkit to find out how they got started on the path to building, sharing and wielding power for equity.”

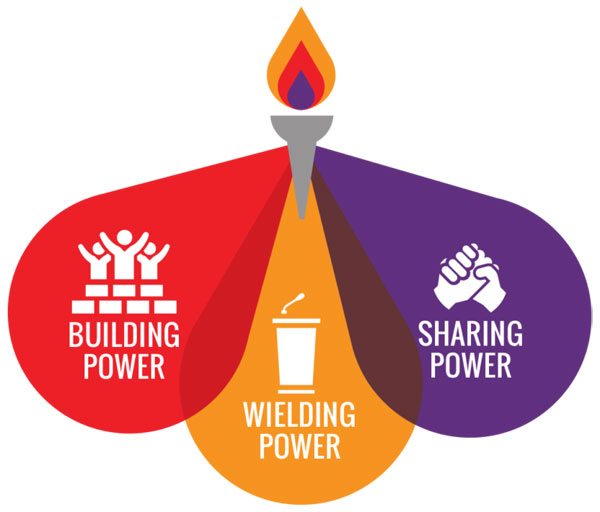

But for those foundations who signed on the dotted line, the idea is to get real—and dig deep. As Ranghelli and Choi write in the report’s first sentence, “To make the world a better place, communities need to build power; funders need to share their power with these communities; and they both need to wield their power to influence relevant audiences and decision-makers.”

This, to say the least, is no small or easy task. After all, as Ranghelli and Choi point out, “Organized philanthropy represents institutions of the wealthy, and giving across the board is increasingly skewed toward the rich.” Moreover, mirroring a pattern that BoardSource has documented in the nonprofit sector itself, “despite years of investment in diversity, equity and inclusion, foundation trustees and executives remain overwhelmingly white and male.”

The toolkit is organized around three themes—building power, sharing power, and wielding power. The toolkit also includes some valuable supplemental materials—these include the readiness assessment test mentioned above, a glossary of social justice terms, a sample six-month timeline as a guide for conducting the complete assessment process, some tips for ensuring inclusiveness in outreach to stakeholders for the “external data” part of the self-assessment process, and a sample “next steps” workshop that includes lines for objectives, timeline, and designation of the person who is overseeing implementation for each given objective.

In a blog post issued upon the report’s release, the Rev. Starsky D. Wilson, CEO of the St. Louis-based Deaconess Foundation and chair of the NCRP board, explains that his foundation plans to be among the first to use the tool because his foundation recognizes that “the case studies we present at conferences are like our personal social media feeds (only showing the best of our lives).” A “reality check,” Wilson says, is needed “to help assess and learn about how well (or poorly) we’re doing building, sharing and wielding power with our partners.”

Below are some of the highlights of the toolkit’s approaches to these three themes.

Building Power

By “building power,” what Ranghelli and Choi mean is to use foundation grantmaking and other tools (convening, investment, etc.) to help marginalized communities build their capacity to act and shape their destinies and organize and advocate on their own behalf. Given the existence of structural inequalities in our society that often disempower these groups, this requires actively promoting systemic change, funding under-resourced communities in their organizing and policy advocacy, supporting cross-sectoral collaboration among community groups, and providing a mix of stable long-term funding while remaining responsive to emerging movements.

Best practices for building power identified in the report include the following.

- Grantmaking has explicit equity and systems change goals for specific communities.

- Board and staff reflect commitment to diversity and inclusion.

- Grant processes are responsive to social movements and urgent needs.

- Internal decision-making prioritizes lived experience and equity goals.

- People of all abilities can access grant programs equally.

- Evaluation and data systems support equity goals.

- Creatively funds and builds bridges across issue silos and constituencies.

- Grant agreements support advocacy.

- Significantly funds civic engagement, community organizing, and advocacy.

The above list of best practices is helpful, but likely not surprising to most NPQ readers. What is unique about the toolkit, however, are the sections that follow. For example, there is an internal questions checklist that is 27-questions long organized into three categories of internal practices (personnel, board), decision-making process, and grant-making processes. There is a 10-question sample survey to use with grantees, peer funders, and other external stakeholders. And there is a discussion guide section that follows to help foundations reflect on the internal and external data they collect. The discussion guide section asks four forward-looking questions:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- Which of the toolkit’s equity-oriented power-building strategies could help us better achieve our goals? The goals of our grant partners? Which do we want to learn more about?

- What are some outside-the-box ideas we’ve heard that could help us support power building among marginalized communities?

- What are our fears or perceived obstacles against engaging in any of these activities? What additional information would we need to decide which strategies to pursue?

- If we are doing all or most of these already, which ones would we like to do better?

Once the goals are set, of course, the challenge becomes one of implementation. Basic principles include taking steps to ameliorate competition that might occur between groups within marginalized communities, fostering a mindset of being willing to ride out the “ups and downs and messiness” of advocacy and organizing, sharing control of evaluation with grantees, making a conscious choice of whether to fund organizing or be the organizer, and being prepared for possible backlash reactions that may arise.

Sharing Power

In concept, the idea of foundations sharing power with grantees is simple, even if it isn’t in practice. As Ranghelli and Choi explain, the idea is not that the power imbalance between funders and grantees is completely eliminated, but it does mean “funders acknowledge their power relative to grant partners and applicants…[and] try to mitigate that imbalance through more inclusive decision-making, such as co-developing what success looks like and how to define impact.”

In talking about sharing power, Ranghelli and Choi cite the work of the Whitman Institute on trust-based philanthropy and trust-based investment, as well as the writings of Vu Le. Among the most important power-sharing mechanisms are grant agreements that provide flexible, operating support (“core funding”) and make multi-year commitments. Not only is this important to enable nonprofits to function more effectively, but it increases grantee power: It reduces the nonprofit’s immediate dependency on the funder for another grant and/or approval of modifications to an existing grant.

Another, even more far reaching practice is to share some of the foundation’s decision-making authority by “bringing community members onto the foundation’s board and staff, onto grantmaking and advisory committees and by fostering community-led planning processes that guide grantmaking decisions.”

Again, the toolkit includes an extensive internal questions checklist and a sample survey to use with grantees, peer funders, and other external stakeholders. The external survey also includes some open-ended questions to solicit both positive and negative feedback from these partners.

In terms of implementation strategies, the writers focus on the importance of navigating the ecosystem of social change actors with care, being mindful of power dynamics within the sector, the importance of humility and building cultural competency, and letting go of the illusion of control, including accepting that, at times, community-driven decision-making may lead to different outcomes than what the foundation may believe to be the “best” decision.

Wielding Power

At first glance, wielding power may seem the opposite of sharing power, but really, what Ranghelli and Choi are talking about here is changing the direction of the power arrow. In other words, a social justice funder, in addition to building the power of its grantees and sharing power with them, also aims to intercede and work with grantees to wield power on their behalf.

The recent Pittsburgh Foundation intervention at the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, highlighted in the report, is illustrative. The Foundation’s amicus brief by itself surely did not cause the Court to declare that the state’s congressional district map violated the right to equal representation under the state constitution, but, as Duquesne University law professor Bruce Ledewitz noted at the time, the foundation’s status as a “respected” institution among elites did carry weight. It also may have helped deflect a narrative that the Court challenge was simply about gaining partisan advantage. As Ledewitz put it, “In this context, the message is, ‘We don’t usually do this, and you know that, and you judges know us as a group that has the community’s good at heart.’”

As Ranghelli and Choi acknowledge, there are risks for foundations in wielding power: “Exercising the power of the bully pulpit can also be conflated with being partisan or with being top-down and dictatorial,” they acknowledge, “but neither is a given.” Indeed, they argue, “philanthropic power can and should be wielded for good, if done in thoughtful ways that acknowledge your institutional and personal privilege and align with the goals and strategies of the communities you are trying to benefit.”

There is more to effective wielding of philanthropic power by social justice funders than using the bully pulpit, however. Citing a 2014 speech by former Ambassador James Joseph, the vision here is one in which the foundation is reimagined as not just a maker of grants, but a “social enterprise that strategically deploys not just its financial capital, but its social, moral, intellectual and reputational capital as well.” According to Ranghelli and Choi, in addition to intervention in the public sphere, this involves hosting convenings, participating in existing convenings, organizing with peer foundations, and using mission-related investing to provide capital that can support community wealth building in low-income communities and communities of color.

As with the two previous sections, the toolkit includes extensive checklists, both for conducting an internal assessment and for surveying external stakeholders, along with some advice regarding how best to process the data collected and how to implement the decisions made thoughtfully.

In terms of implementation, Ranghelli and Choi highlight the importance of ensuring that the foundation makes sure its interventions are invited by the community, is prepared for pushback, works to complement community groups (rather than drowning them out), and is clear with partners in advance if its participation is only for a limited period of time.

Concluding Thoughts

As Wilson of the Deaconess Foundation observes, “The privilege of philanthropy and power dynamics with many of our partners allows us to blame others for a lack of missional progress and social change. Meanwhile, we pat ourselves on the back for valiant efforts. Those of us who regularly gather and are blessed to don platforms to discuss and frame explicit equity work, efforts in marginalized communities and the latest research increasingly avoid conversation about political wins and winds. Yet, our theories don’t become action without power.”

The toolkit, of course, is hardly the last word on these matters. But for foundations seeking to turn promises of equity into reality, the self-assessment process outlined in the toolkit provides a rigorous—and thorough—roadmap of how to at least start to get there.