Editors’ note: NPQ has been watching the state of workplace giving closely during the last two decades. Most of the time, we focus on United Way, which is certainly the biggest and best known of the types, but the field also includes other entities, such as workplace giving programs for state and federal government employees. The latter is called the Combined Federal Campaign (CFC), and this entity, which many nonprofits don’t know much about, has seen the money it raises not only decline but plummet over the past 14 years. It has undergone many attempts at fixes but hasn’t recovered—even for a year or two—any of the revenue levels of previous years. So, what happened? Here, an insider provides NPQ readers with a bird’s-eye view of what has occurred with the CFC, with an eye toward tracking patterns of decline in workplace giving campaigns in general and investigating whether this is an effort that can be saved.

Can the CFC survive?

It is an unsettling question, given that the U.S. government’s workplace fundraising program has been operating for almost six decades. Formally launched by the Kennedy administration, the Combined Federal Campaign has over the years raised more than $8 billion on behalf of tens of thousands of national and local charities.

Today, however, the CFC is in trouble, plagued by flagging donor interest and competition from other modes of giving. The government has been responding to these pressures, trying to reshape and refresh the campaign. But the bad news has only seemed to get worse, and it is reasonable to wonder if, in a year or two, advocates of a philanthropic program that has served as the inspiration for states and municipalities will finally say, Enough. Will those of us who have spent years working to strengthen the CFC conclude that its day has passed?

The 2018 campaign is under way, and federal employees have begun to pledge to eligible charities. We will know the results in January 2019. As we do every fall, we await those numbers with hope. Those worried about the future of the campaign should not wait until January, however, to consider how we arrived at this troubling moment. If there are changes to be made to the campaign in order to reverse a decade of decline, now is the time to bring them forward so that donors and charities alike can debate potential improvements.

Workplace giving is embedded in the history of American philanthropy. For decades, it offered average citizens the chance to support the growing charitable world, donating a small amount with each paycheck. Over the years, workplace giving reinforced the American community, as workers were able to share with each other their interests in causes and groups.

Today, our country is being sorely tested; our sense of community is being shredded at every turn. It would be nice to reinvent workplace giving so that it could help remind us all of what we have in common.

Reinvention is the challenge confronting the CFC. It is not a matter of choosing this fundraising technique or that latest technology but rather building on the readiness of average people, of employees in their workplaces, to help others. As a first step toward that end, we must see where the CFC is.

A Decade of Decline

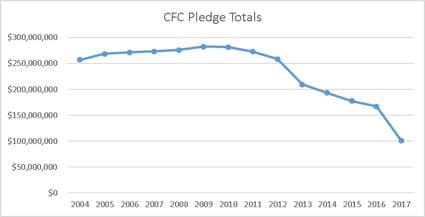

The last decade has been an unhappy time for the CFC. The following graph is based on figures released by the agency that administers the campaign, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM). Their numbers show a grim decline in the amount pledged.

The peak year of the CFC in terms of money raised was 2009. Federal employees pledged slightly more than $282 million that year. In the fall 2017 campaign, the last CFC cycle for which we have final figures, pledges were about $101 million—a drop of 64 percent over the nine years. If one adjusts for inflation, the news is even worse: adjusting for inflation reveals that the 2017 pledge result was lower than in any year of the campaign, back to 1972—for as far back as the government has published figures.

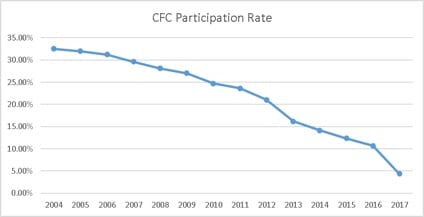

A second graph shows an equally disturbing trend, the drop in employee participation.

In 2009, government statistics show that four million employees (civilian and military) were solicited. Almost 1.1 million employees elected to pledge to one or more charities. In 2017, the number of employees solicited was about the same, about 3.9 million, but the number of donors plummeted to 169,000. In nine years, the number of donors dropped almost 85 percent. The rate of participation, which had been over 25 percent in 2009, was down to slightly more than 4 percent.

One employee out of twenty five.

Flawed Reforms

As campaign results began to slide, the government decided to use the occasion of the CFC’s fiftieth anniversary to convene a task force consisting of federal employees, charity representatives, and others. I was one of those who served. The CFC 50 Commission offered a range of possible approaches to improve the campaign, publishing its report in July 2012.1

Two years later, in the spring of 2014, OPM published new regulations to reshape the CFC.2 They were, to say the least, controversial. Many, including this writer, warned that proposed changes would harm the program. In the end, the sweeping redesign of longstanding systems proved far more difficult to pull off than government staff anticipated: the new rules were not finally implemented until the 2017 campaign. The results have been dismaying. The following sections discuss a few of the problematic areas that the campaign now lives with.

Loss of Local Fundraising Expertise

Over the years, the CFC had developed a nationwide network of local organizations whose staff knew the charities and donors in their communities. These local administrators were always nonprofits and were supervised by local federal volunteers. In part because so many United Way chapters had served as local administrators through the years, strong connections across the country allowed for substantial sharing of best practices.

OPM eliminated this community-based network in favor of a handful of more remote companies—which OPM calls “Outreach Coordinators,” or “OCs”—that no longer need be nonprofit. These Outreach Coordinators are charged with promoting the campaign. Sadly, the government’s own procurement rules have shaped the Outreach Coordinator culture. The OCs appear to view each other as competitors, angling for the next round of government contracts. Efforts to exchange best practices are undermined.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As part of its reorganization of the CFC that took effect in 2017, the government sharply reduced the number of campaign zones, from 147 to 37. Zones became far larger. New England, which was divided into four zones for the 2016 CFC, became a single zone in 2017. California dropped from five zones in 2016 to two in 2017. One of the new zones is roughly the size of Peru! Not surprisingly, those working to promote the campaign are finding that many donors have become remote. Scale brings economies, but it can also diminish face-to-face contact, which lies at the heart of fundraising.

We are only in the second year of the newly designed CFC, but already questions are being raised about the productivity of Outreach Coordinators—let alone the advisability of switching out a community-based network for campaign promoters, who are more remote from the potential donor and seem quite focused on chasing the next contract (which, given the large amount of money the government is dedicating to these contracts, is no surprise). The results in some zones are unsettling.

Flawed Online Search

To handle back-office functions, the government created a new “Central Campaign Administrator.” OPM hired two companies, one nonprofit and the other for profit, to build and operate a new website to handle charity applications, donor pledging, and the reporting of pledge results. Key to the work of the administrator was the launch of an online system through which federal employees could search for charities they wished to support.

Problems with the new website were, perhaps, inevitable (this is the government, after all). The new online search system was plagued with difficulties, often returning lists of charities that had nothing to do with the terms entered by prospective donors. If you searched for “art” you would see lists of groups that included “earth” in their name. If you searched for “cat” you would see groups that used “educate” or “education” in their name. OPM staff have worked hard to clean up the online mess, and the search system is improving. Even OPM acknowledges, however, that a more substantial redesign may be in order for the 2019 campaign.

In its eagerness to sweep away old systems, OPM has been eliminating the system that donors had used for decades to look for charities: the printed directory. Fewer and fewer of these “old technology” books are printed each year, and donors often find that their only option is to go online—and hope they can find the groups they seek.

Rising Costs

Ironically, running the CFC is now more expensive than it was before the government’s changes. OPM had hoped that replacing local administrators with regional promotional companies, reducing the number of campaign zones, and consolidating back-office and website functions would yield substantial savings. Costs have risen, however.

In its annual report on campaign results, OPM stated that the budgeted cost of the 2017 CFC was about $26 million, split between the Outreach Coordinators and the Central Campaign Administrator. The year before—the last year of the old system—the number was $25 million. Costs are going in the wrong direction.

Up-Front Fees

Workplace giving programs have long paid for their operation by withholding money from donated funds. The CFC was no different, until the government decided to require that charities pay up-front fees in order to participate. OPM hoped the new fees would cover the full cost of the campaign, but too many groups walked away from the CFC, and that ambition fell flat from the very beginning. As a result, the government was forced to withhold millions of dollars from 2017 donations before any money reached charities. It will have to do so again for the 2018 campaign.

Whatever hesitation charities may have felt about the CFC when the up-front fees were announced has only deepened as the reality of declining pledges has hit home: many charities are losing money on the campaign.

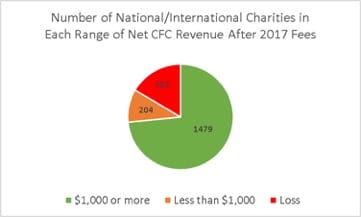

The following table shows how well national groups performed in the 2017 CFC. We can see that one group in six paid more in OPM fees than they raised. If we add the charities that raised less than $1,000, the number of groups that lost or almost lost money rises to one in four.

The campaign is now trapped. Costs have held steady due to the government’s expensive contracts with OCs and the Central Campaign Administrator, charities are leaving the program, and pledges are declining. OPM can cut the marketing and promotional budget to be spent across the country, but who then will attract donors? OPM can increase the fees charged up front to the charities, but that will simply lead more groups to walk away.Not surprisingly, charities have responded to the drop in pledges and OPM fees by themselves withdrawing from the campaign. The sharpest decline was in 2017, when the number of participating groups dropped by more than half. The financial implications are as obvious as they are threatening. Unless the CFC can improve its results, the cost of the campaign will consume more and more of the amount paid by charities and pledged by donors. At some point, the campaign’s administrative overhead will become politically—not to mention ethically—unsustainable.

A Way Forward?

In the short run, the future of the CFC likely hangs on a single thread: improved pledging. If pledge totals in the fall 2018 CFC rebound from the dismal results of last year, the pressure on the CFC will ease. More charities may enter the 2019 campaign (and pay the fees), and the administrative overhead of the program, now at a stunning 25 percent, will decrease.

In the next year or two, OPM can further improve online search so that donors can more easily find the groups they want to support. The government may also be able to back away from some of its expensive provider contracts, thereby allowing the administrative costs of the program to come down. But recovering pledges, fully functioning search, and less costly contracts will likely only buy the CFC a little time. The powerful forces challenging workplace giving will remain. Federal employees have alternatives to the CFC; one need look no further than personal credit cards.

Ironically, the future of the CFC—and the future of workplace giving as a whole—lies in its past. The future is tied to the ability of workplace campaigns to engender a spirit of community where donors take the lead. Ask any fifth grader raising money for the local sports team, or the board member raising money for the local museum; it is the person-to-person request that drives successful fundraising.

Perhaps surprisingly, as public-sector workplace giving flounders, pockets of success can be found in the private sector. No less a presence than Microsoft touts a giving program that led in 2017 to donations of $156 million and 700,000 volunteer hours from its employees, who participated at a rate of 75 percent. An important component of the Microsoft program seems to be corporate support of employee initiatives. A February 2018 article in Forbes reported that many companies are dedicating corporate resources (time and money) to support their employees’ charitable giving and volunteer activities.3 These companies have found that doing so pays off in a more stable and engaged workforce.

One secret to success seems to be allowing employees to take the lead rather than trying to herd them into a top-down structure. Adding a social media component to the CFC’s online pledge system could give employees opportunities to take initiative in their own charitable efforts by recommending charities to colleagues, or even collaborating with others who share their interests. Collaborative fundraising is on the rise, as evidenced by the increasing use of crowdfunding platforms. The Collective Giving Research Group reported in 2017 that giving circles had tripled in the prior ten years.4

As OPM consolidates the CFC, placing its faith in online systems, it undermines the very essence of what has made the CFC work for decades: person-to-person contact. I want to help; will you?

Reviewing a list of eligible charities while sitting in front of a computer does not capture the magic of workplace giving. It is an isolating act. Let donors come together where they work; let them share their excitement and their commitment. It has worked for more than a century; it can work again.

Notes

- Federal Advisory Committee Report on the Combined Federal Campaign (Washington, DC: U.S. Office of Personnel Management, July 2012).

- “Final Rule to Amend the Combined Federal Campaign (CFC) Regulations Fact Sheet—April 11, 2014,” Reference Materials, Combined Federal Campaign, U.S. Office of Personnel Management website.

- Glenn Llopis, “Reinventing Philanthropy As An Employee-Centered Growth Strategy,” Forbes, February 5, 2018.

- Jessica Bearman et al., The Landscape of Giving Circles/Collective Giving Groups in the U.S., 2016 (Indianapolis, IN: Collective Giving Research Group, November 2017).