NPQ, in partnership with the First Nations Development Institute (FNDI), has published a series of Native American activist writers who highlight the practices of community building in Indian Country this fall. This essay, also produced in partnership with the First Nations Development Institute, is the first of three articles that we are publishing from the perspective of philanthropy. (Additional related articles can be found at this FNDI webpage.) Expect more from NPQ and FNDI in 2020.

For philanthropy to support initiatives in Indian Country, it is not necessary to build a comprehensive knowledge of Indigenous cultures. It does require a willingness to unlearn myths, operate from a standpoint of respect and reciprocity, and be willing to support relationships that foster growth, creativity, and the natural progression of learning.

I am the product of my ancestors’ dreams and my relatives who came before me. Without their dreams and love, I would not be writing this today. I am a Cherokee woman who has worked at NoVo Foundation as Program Officer for Indigenous Communities for over four years. I’d like to offer my experience and observations as to why more Indigenous-led work should be supported and how you can be a part of it.

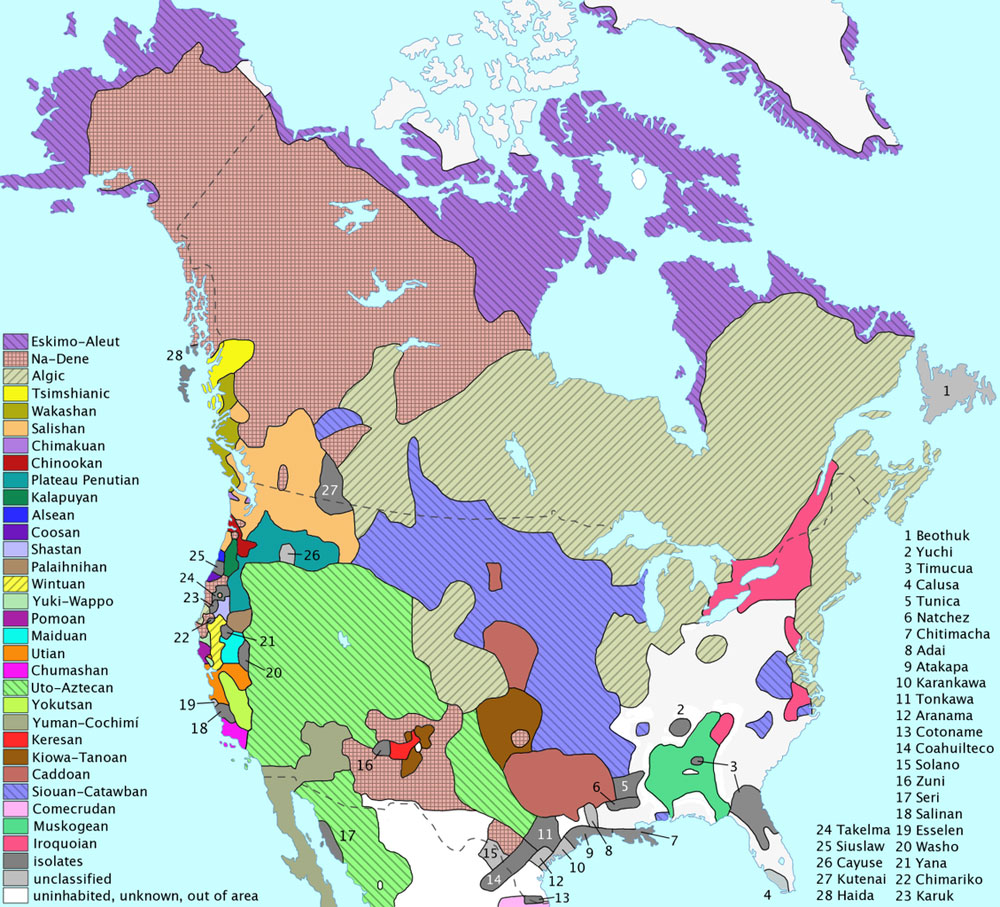

To begin, think about where you’re sitting as you read this and take a moment to acknowledge the traditional territory of the Indigenous peoples whose land you are on. If you don’t know the name of the people(s), it’s okay. Remember, we’re planting seeds. (For the overachievers, you can go to Native Land and search the territory you’re curious about. You may see overlaps; people moved around, some were unwelcome visitors, and boundaries weren’t static. The Indigenous world was complex and cosmopolitan.)

1. Indigenous communities and Indigenous-led work are in your foundation’s footprint. If you’re not supporting it, you’re missing some of the most innovative and transformative work out there.

To those not familiar with this work, it’s holistic. What does that mean exactly? In one community, it’s a Native language immersion school that created a board game in the language being taught for its students and shared it with the local elementary school so more students could learn their Native tongue. As a result, more young people are speaking their tribal language and teaching their relatives. This immersion school is also working with their tribe to replace red meat with buffalo, a traditional food, in school lunches. The school purchasing the buffalo gives business to the tribe’s buffalo enterprise and recirculates dollars locally. Skinning and processing the buffalo gives the students an opportunity to use their language and better understand a part of their culture. The students do not use playground equipment; instead, they learn and play traditional games. The games reinforce life skills, academic learning, and community values. Holistic work, then, is interconnected; each part of the whole is essential for the whole to make sense.

At NoVo Foundation, our Indigenous Communities Initiative is a fundamental part of our mission to build a more just and balanced world. We support about 175 organizations in the US and beyond, predominantly Indigenous led. We support grassroots, national, and international efforts that include language revitalization, strengthening of food systems, cultural practices, law and policy frameworks, environmental justice, ending violence against Indigenous girls and women, and leadership development for Indigenous girls and women. In most instances, this work proceeds regardless of a foundation like NoVo. However, we hope that our flexible, general operating support helps organizations advance their work even more rapidly.

If you’re reading this and you work in philanthropy, I bet there is fantastic Indigenous-led work within your foundation’s footprint and focus areas. Think of it as being a good neighbor in your footprint. Call it diversity, equity, and inclusion, but don’t wait to support it, as I believe this work will inspire you.

2. Don’t believe the spin and stereotypes about Indigenous people and tribal governments.

Contrary to what the 1953 film Peter Pan would lead you to believe, we do not make noise by fanning a hand over our open mouths while calling out “wha.” Thanksgiving is an untrue story, part of a national myth that arose in the late 1800s—right around the time Indigenous people were largely confined to reservations and record numbers of European immigrants arrived. It was a way to close the “frontier” and to weave all the newcomers into a national fabric.

We’re not all Sioux, Cherokee, or Navajo living in the Upper Great Plains, Oklahoma, or the Southwest. We’re not all “taken care of” by the US government, or alcoholics, or rich from gaming. We are human—complicated, contradictory, beautiful, and diverse in our thoughts, opinions, and actions.

History books, school systems, professional sports, Hollywood movies (John Wayne: two thumbs down), policymakers, and the US Supreme Court have done a fantastic job of minimizing Indigenous people through stereotypes and mascots, portraying us largely as dead, historical figures (choose between bloodthirsty savages or children of nature); and making invisible those of us who remain.

By presenting us as static or historical artifacts, or not presenting us at all (think categories like “statistically insignificant” or “other”), it’s easier to absolve and deflect guilt for taking our land, committing genocide against our ancestors and relatives, and failing to make amends. The same is true of families and the stories people tell themselves about how their ancestors arrived in and settled what we currently call the United States. I know, I have some non-Indigenous relatives.

However, this doesn’t mean that non-Indigenous people need to feel guilty and suffer from inaction. Examine and free yourself from this inaccurate history and these destructive stereotypes. For a snapshot of accurate Indigenous history, there are some great timelines you can visit including this one from Indian Land Tenure Foundation and this one from Institute for Native Justice. For a broader overview, check out First Nations Development Institute’s recommended reading lists at this link. You can immerse yourself in a vast body of history, literature, and poetry written by and in support of Indigenous peoples.

A few words about what this work isn’t. It’s not an attempt to kick out the descendants of settler-colonists, rip up the concrete, and repopulate the Western Hemisphere. We already know the answer to the late Oneida comedian Charlie Hill’s question posed on The Richard Pryor Show in 1977: “You guys gonna stay the night?”

When Indigenous people seek to manage our lands, prosecute wrongdoers in our communities, or oversee other aspects of life in our communities, we are exercising our inherent rights as independent, political governments and peoples. I recently had to explain to a large organization that food “sovereignty” had nothing to do with lobbying. Sovereignty is the authority to self-govern. Why is this so unsettling? I think because there is a perception that some must lose power if others attain it. I offer that when we each have power, the whole is strengthened.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

3. Relationships make this work (and all other work) possible, and relationships require effort. One funding relationship is a starting place. I don’t think you’ll be disappointed.

Philanthropy comes from the Greek philo, meaning “the love of” and anthropos, meaning “human beings.” Indigenous peoples understand philanthropic concepts inherently because of fundamental elements in our worldviews: everything is related, and value is placed on the good of the whole. Since everything is related, relationships are at the core of being human, as are respect and reciprocity.

As a result, relationships in Indigenous communities are much less transactional. I offer that true, systemic change begins with and is sustained by people. Rigid timelines, efficiency, and scalability can inhibit the growth, creativity, and the natural progression of learning. Why not extend this flexibility to those philanthropy supports? NoVo tries to do this in its work.

I’ve been told that Wilma Mankiller attributed the Cherokee Nation’s success under her tenure as principal chief to relationships. (Wilma was good at building relationships. She received Independent Sector’s John W. Gardner Leadership Award and spent 12 years on the Ford Foundation’s board.)

It sounds obvious, but it bears mentioning that you can’t work with people when you don’t know them. Indigenous communities have had a lot of experience with extractive visitors (settlers, anthropologists, oil businesses, etc.) and benevolent do-gooders (missionaries, short-term volunteers, etc.)

Chances are Indigenous people aren’t going to seek out non-Indigenous folks because those exchanges haven’t gone so well. So, it’s a good idea to go to Native communities.

Some people posit that 80 percent of life is showing up. This is especially true in Indigenous communities. Showing up helps give people confidence that plans are for real and outsiders, especially, might be worthy of trust—with time. It shows respect for relationships and what is happening in the community.

Since Indigenous communities are less transactional, they are more attuned to the life events that influence their relationships: ceremonies, deaths, and unforeseen events, both good and bad. If someone dies, it’s very possible that your grant report will be late. You may or may not hear about it. You will likely get your report. If you don’t, it’s a communication wrinkle to iron out—probably not a reason to suspend funding indefinitely. Wouldn’t you want to be cut some slack in the same situation? This goes back to the meaning of philanthropy.

4. Don’t overthink it. The histories of Indigenous communities are complex. It’s not complicated to support Indigenous-led work.

I’ve heard people say that it’s too complicated to work with Indigenous communities. Or people say things like tribal governments are corrupt or ineffective, the community atmosphere is dysfunctional, community members are unreliable, or it’s just too difficult to understand the history and current events that have created present-day circumstances. This could be said of any community. Complexity is a poor excuse.

Indigenous people do not expect non-Indigenous people to know everything about their histories (see the book list and timelines mentioned above). Not everyone who is Indigenous knows their history. Making an effort to educate and inform yourself about a community’s history is appreciated, as it is anywhere. Another great way to learn is by asking—then actually listening—to the response. You don’t need to be an expert in Indigenous history, politics, or culture to fund Indigenous-led work.

Also, no one is expecting you to walk into a community and know all the cultural protocols. As a guest in any community, it behooves you to arrive and behave in a thoughtful, respectful manner. This means asking for guidance about what to do and not do and not assuming that people are on display for visitors’ consumption (taking a photograph without asking permission first, etc.). Listening and observing is nearly always a good idea.

There are a few ways to support Indigenous-led work. One is through intermediaries that can re-grant to nonprofits, fiscally sponsored projects, and tribal governments. There are several national, Indigenous-led organizations that offer this as part of their work. One nice thing about intermediaries is that they have many relationships that have often taken years to develop. This is helpful since many philanthropies’ grant strategies change regularly. Working with an intermediary can minimize the disruption that occurs when the philanthropy’s “partnership” ends.

By working with an intermediary, though, the philanthropy may be asking that organization to add staff and infrastructure. Therefore, attention needs to be paid to whether the intermediary wants to do this work, over what period of time the philanthropy wants to support the work, and what the organization needs to do it sustainably. There is tension (think externalities, paternalism) in working this way. In my experience, this must be minimized by the philanthropy and intermediary having frank conversations before and throughout the grantmaking.

Other ways are directly or through donor-advised funds. For philanthropies that haven’t supported Indigenous communities, it’s worth taking time to learn about the region or area of work your institution intends to support (history, array of organizations that work in the area and what their goals are, etc.) before making grants. Talk with other foundations who make grants in the region or area of work you are considering. Go to regional gatherings of grantmakers and/or nonprofits, if they exist. This will help you develop relationships and, likely, make more successful grants over the long term.

Indigenous people and Indigenous-led organizations are resourceful and generous. We embrace humor (how else do you think we survived attempted genocide?), and we demonstrate systems thinking. If you aren’t supporting the work in our communities, I encourage you to join us.

Hester Dillon, Cherokee Nation, serves as Program Officer for Indigenous Communities at NoVo Foundation. She notes, “I acknowledge the traditional territories of the Eastern Shoshone, Goshute and Ute peoples on whose land I traveled as a guest as I began writing this article. I also acknowledge the traditional territory of the Shoshone-Bannock, on whose land I currently live in what is considered southwest Montana. Despite our society’s emphasis on individual accomplishment, I do not believe we do anything alone. I am honored by and say wado (thank you) to those who read this article and offered input.”