In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt first launched the New Deal, a series of reforms, regulations, programs, and public works projects designed to help the struggling economy. Nearly 100 years later, a group of young people are coming together to support another “New Deal”—one focused on environmental justice and education.

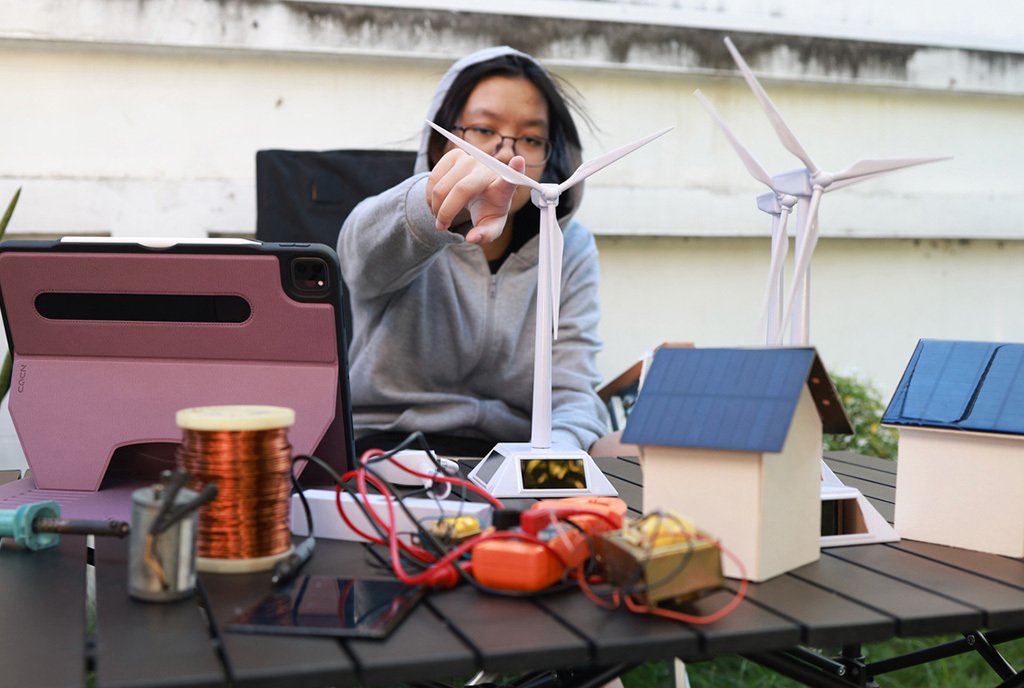

Youth have been leading the fight for climate justice for a long time. They’ve organized and led protests, testified in front of government officials and international bodies, and—more recently—taken their battles to the courts, seeking to slow the impacts of climate change through legal channels. Young people are now getting directly involved in policymaking to improve the environment of classrooms across the country.

With the Green New Deal for Schools, youth are calling for improvements to school buildings to withstand an increasingly volatile climate, and changes in school curricula. Students spend about 180 days per year in school, making it the place they spend nearly half their time, yet many are not being taught the science of climate change, which student activists feel is a denial of the reality quickly escalating all around them and one of the greatest concerns of their lives.

As 17-year-old Adah Crandall told the Guardian: “We are prepared to do whatever it takes.”

Bringing the Movement to Schools

Crandall is an organizer with Sunrise Movement, a climate justice collective led by youth based in Portland, OR. Founded in 2017, the group advocates for political action regarding climate change.

That action includes supporting the Green New Deal, which, as defined by Sunrise Movement, is a “congressional action to mobilize every aspect of American society to 100% clean and renewable energy, guarantee living-wage jobs for anyone who needs one, and a just transition for both workers and frontline communities.”

The Green New Deal was first introduced four years ago. With nearly a hundred cosponsors in the House and 14 in the Senate, the plan failed to advance in the Senate but was reintroduced in April 2023 by Senator Edward J. Markey (D-MA) and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY). As NPQ wrote in March 2023, the Green New Deal has also “influenced some of the biggest pieces of climate legislation at the federal, state, and local levels. The resolution signaled a stark move away from regulatory policy largely disconnected from communities’ desires for environmental and economic justice.”

School buildings across America are old, in disrepair, and energy inefficient.

The plan for the Green New Deal for Schools, according to Sunrise Movement, is to “bring the movement for the Green New Deal to every student, classroom and school in this country.” This includes a push for schools to teach climate justice, to provide vocational training for students moving into green jobs, and for schools to have climate disaster action plans. As reported by the Hill, “The hope of the campaign is to get district-wide climate policies enacted, with the ultimate goal of obtaining federal legislation to change schools across the country.”

Dangerous Heat, Outdated Buildings

The proposed Green New Deal for Schools also calls for updating school buildings and buses in response to climate change, making them better able to function in extreme weather. School buildings across America are old, in disrepair, and energy inefficient. Hundreds of thousands of students must attend school in the late summer and early fall months, which are often scorching as temperatures continue to rise around the globe. For many of these students, classrooms do not have air-conditioning.

As Sarah Zaleski, schools and nonprofit program manager at the Department of Energy, told Scientific American, “Some have relied on more passive systems like opening windows. That just doesn’t cut it anymore.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Student athletes have fallen ill after practicing or competing in dangerous heat, a problem exacerbated by worsening air quality due to wildfires or pollution. Many schools have cancelled classes or released students early in an attempt to deal with the escalating temperatures and fluctuating air quality.

The buses that transport students to and from their buildings also need upgrading. One of the goals of the Green New Deal for Schools is for school buses, along with school buildings, to run on 100 percent clean energy. The plan also demands schools provide free, healthy—and ideally locally sourced—lunch to all students.

“Our generation is on the front lines of this fight.”

The Right to Learn

Sunrise Movement, which held a camp over the summer to train young environmentalists in action and advocacy, is partnering with more than 50 schools nationwide to fight for the plan. Some students from the group will join lawmakers in Washington, DC, to officially announce the Green New Deal for Public Schools Act.

“Our generation is on the front lines of this fight and it’s time for our school districts to take real action,” Sunrise Movement organizer Crandall told the Hill.

“We don’t learn about climate change at all.”

The group formed in direct response to the denial of climate change and the mounting legislation in Republican-led states discouraging or outright banning the teaching of climate science in schools. The proposed legislation would provide funding to update schools, and to hire additional teachers and modernize curricula.

“We don’t learn about climate change at all,” 16-year-old Summer Mathis, a student in Georgia, told the Guardian, which reported that under that state’s “dismissive concepts” law, “teachers are unable to talk about climate justice and the unequal toll of global heating. In other Republican-led states, factual climate education is being targeted directly.” Texas, Idaho, and Florida are but a handful of the states stripping mention of climate change from textbooks or supporting teaching materials from conservative groups, which often include climate change denial and other dangerous misinformation.

“Being a youth right now is really scary,” 15-year-old Aster Chau told the Guardian. “It’s really scary knowing that I’m underage, and can’t vote to elect the people making these big decisions about our futures, not having a say in that.” Though Chau acknowledged “feeling the weight of the climate crisis,” the student from Pennsylvania also spoke to the power of having peers. “Being with one another is really helpful, knowing that I’m not just the only one who is feeling this pressure, but also extreme passion in fighting it.”